Who might be hurt by fallout from the US-China trade war? Singapore, Taiwan, Malaysia, to name a few

Aidan Yao says a sizeable amount of Chinese exports consist of components made elsewhere, which means the trade dispute with the US will hit China’s partners in the global supply chain

Another round of trade negotiations between the US and China came and went without any progress in resolving the dispute. With tariffs on US$100 billion of products – US$50 billion on each side – fully implemented, the two sides are facing a further escalation involving taxes on another US$260 billion of goods – US$200 billion of Chinese goods and US$60 billion of US goods. The trade war is now in full swing and is set to last, at least, until the US midterm elections.

So much has been written on the topic, with almost uniform conclusions: a trade war is bad for the United States and China, and will adversely affect the rest of the world through supply chains and financial markets.

Economists have generally put out solid work on the first aspect – involving the US and China – but good analysis on the contagion impact has been harder to find. Which could be the worst-hit countries, outside the US and China? What is the nature, scale and breadth of the spillover? And does everyone stand to lose?

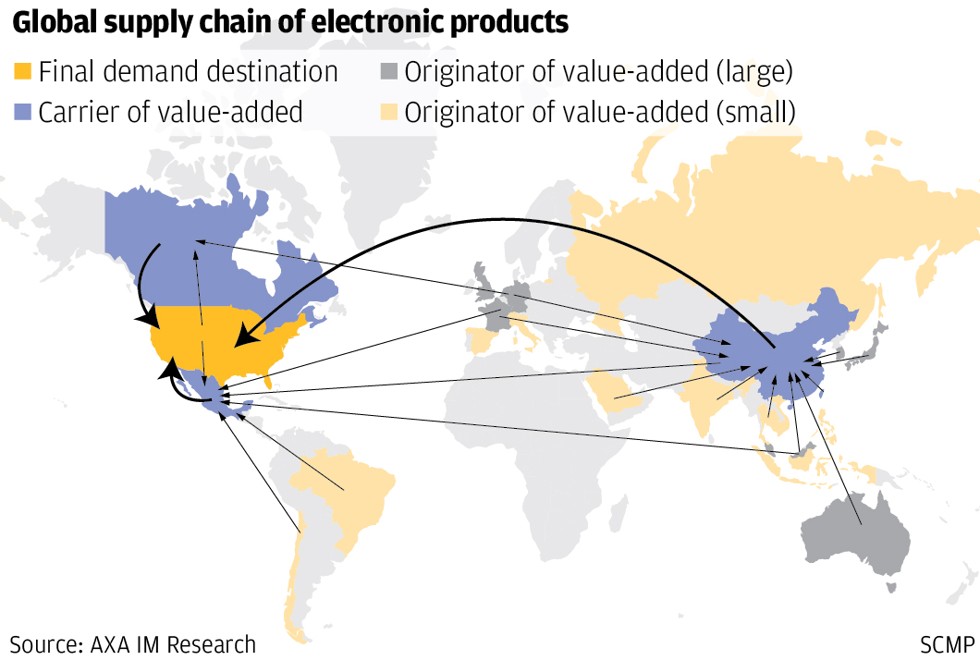

Let’s start by recognising China’s important position in the global supply chain, which is linked to the manufacturing of many products that have been, or will be, hit by the US tariffs. According to China’s customs, over 30 per cent of the country’s total exports in 2017 were processed and assembled products that incorporated other countries’ inputs and components. This means that even though the final goods were labelled “made in China”, the profits were not made by Chinese producers alone.

For products such as electronics, which rely heavily on the global supply chain, over 40 per cent of the added value in mainland Chinese exports can be traced to external partners. Asia’s technology leaders, such as Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and Singapore, are important creators of the value embedded in China’s exports around the world.

If only the products destined for the US are considered, China, along with Mexico and Canada, has effectively functioned as a carrier of the value that originated in upstream producers, even though it has also become a value generator over time.

This interconnectedness means that the impact of the trade war will be contagious. As China’s exports to the US decline, its import of components and inputs from other partners will drop too, sending shock waves through global production lines. Japan, Korea and Taiwan appear the most vulnerable, by dollar amount. But in terms of gross domestic product, Singapore is the most exposed to the fallout from the trade war, followed by Taiwan, Malaysia, Korea and Vietnam.

Assuming 25 per cent tariffs on US$250 billion of Chinese goods, the direct impact on these economies could range from about 0.2 per cent of GDP (for Korea) to over 0.6 per cent (for Singapore).

While Asia will bear the brunt of the trade war, some European countries, such as Germany, Switzerland and Britain, will also feel some pain, over generally less than 0.1 per cent of GDP.

Finally, it is not all bad news. For China’s competitors in the US market, many of whom are also its supply chain partners, there are potential gains in market share. China commands the leading market share in electronics and machinery exports, which have been targeted by the US tariffs, and its loss may be its rivals’ gain.

Assuming that China’s loss will be redistributed proportionally to its competitors, potential beneficiaries will be Mexico, Taiwan, Canada, Korea and Japan. For Mexico, China’s market share could be worth up to 1.2 per cent of its GDP. This would more than offset the loss from the impact of the first round of tariffs – Mexico is also a tiny value contributor to China’s exports – leaving it as the biggest net beneficiary of China’s exit from the US market. Canada would also benefit, though much less than Mexico.

Most other countries, particularly in Asia, would find limited offsets, making them net causalities of the trade war.

Two key caveats: first, this analysis is based on the crude assumption that the Chinese will pass the tax increases along to their supply chain partners, which will react by cutting exports and production proportionally.

Second, China’s competitors will be able to ramp up production quickly to pick up some market share. This is obviously unrealistic though, unless producers have the spare capacity of both investment and workers. Hence, while gains are possible, they will take time and effort to realise.

Overall, the popular belief that the trade war is bad for everyone except a precious few of China’s competitors seems to hold. As the Korean saying goes, “When whales fight, the shrimps’ backs are broken”.

Aidan Yao is senior emerging Asia economist at AXA Investment Managers