As central banks turn dovish, how loose will this year’s monetary policy be?

- Nicholas Spiro says the Federal Reserve’s more cautious stance towards raising interest rates has set the pace for other central banks. However, while the US economy may be showing signs of slowing, China and Europe are of greater concern

In the middle of November last year, the yield on one-year Chinese government debt fell below its American counterpart for the first time ever, according to data from Bloomberg, dropping to 2.5 per cent as Beijing’s shift towards more growth-supportive measures gathered pace. The yield gap between the two countries’ 10-year bonds had also narrowed sharply, dropping to just 30 basis points as the divergence between Chinese and American monetary policy gained momentum.

It was not just the Federal Reserve and the People’s Bank of China that were parting ways. A succession of US interest rate increases, coupled with expectations of further tightening this year as America’s economy powered ahead, contrasted starkly with a slowdown in growth in the euro zone. By early November, the spread between US and German 10-year bond yields had increased to nearly 2.8 percentage points, its widest level in almost three decades.

Divergences in monetary policy were also becoming more pronounced across emerging markets. While some economies, such as Brazil and Colombia, reduced borrowing costs to help stimulate growth, others, notably Indonesia and the Czech Republic, joined the Fed in raising rates with the aim of maintaining financial stability.

Yet, since the beginning of this year, a synchronised global slowdown, driven by a sharp deceleration in China and Europe, has taken root. The publication last Tuesday of survey data on global manufacturing and service-sector output, compiled by IHS Markit, showed that growth slowed to its weakest level last month since September 2016. This has brought about a shift towards looser – or at least less tight – policy stances in both advanced and developing economies.

The dovish tilt is being led by the Fed. In a dramatic change to its outlook in December when it raised rates and signalled further hikes this year, the Fed announced at its meeting last month that it would be patient before making any future adjustment. It even hinted that the next move could be a rate cut if America’s economy – which remains buoyant – succumbs to the global slowdown.

This abrupt reversal on the part of the world’s most influential central bank has changed the policy landscape, making it easier for other central banks to move in a more dovish direction.

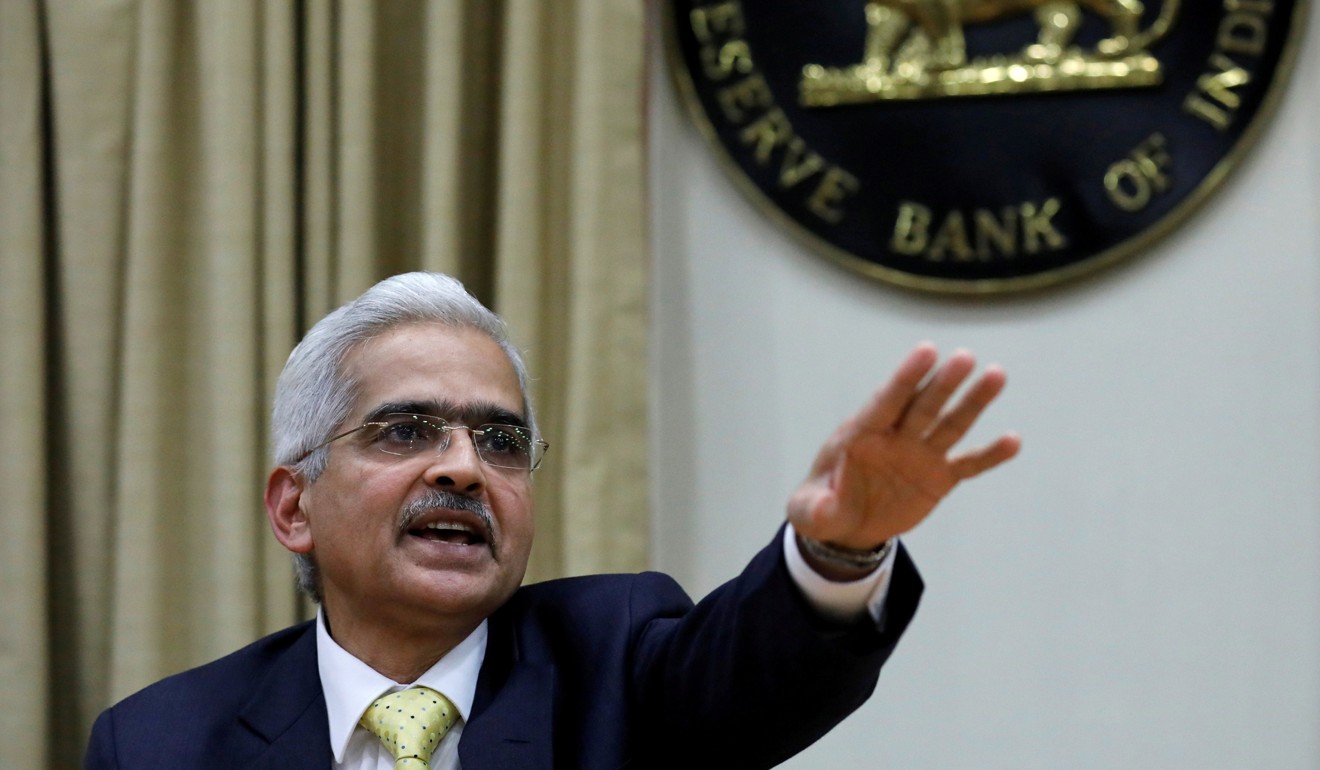

Last Wednesday, Philip Lowe, head of the Reserve Bank of Australia, warned of an accumulation of domestic and external risks which made a rate cut more likely, causing the Australian dollar – a proxy for sentiment towards China – to suffer its steepest daily decline since last August. The following day, the Reserve Bank of India unexpectedly cut rates, citing subdued inflation. Central banks in other emerging markets that hiked rates last year, notably the Philippines and the Czech Republic, are also striking a more dovish tone.

However, it is in Europe where the scope for sharper reversals is most apparent.

On Thursday, the Bank of England slashed its forecast for growth in Britain this year from 1.7 to 1.2 per cent as it shelved plans for further rate increases, warning that the risk of a recession would rise if the UK left the European Union at the end of March without a deal and no transition arrangements in place. The same day, the European Commission painted a bleak picture of growth in the euro zone, forecasting that Italy – which is already in recession – will barely grow this year, while Germany will expand by just 1.1 per cent.

As I argued previously, this leaves the European Central Bank, which terminated its quantitative easing programme last December, in an awkward position. If even the Fed is giving itself room to cut rates when America’s economy is still growing at a relatively brisk pace, then the ECB, which downgraded its outlook for the euro zone last month, should have already eliminated the possibility of a rate hike later this year. A more dovish stance is only a matter of time.

The Fed-led shift towards a looser policy stance has already contributed to an easing of financial conditions across developed and emerging markets. Global stocks are up more than 7 per cent this year, while spreads on corporate bonds have narrowed significantly.

However, the US dollar, which began to weaken in December as investors started pricing in a more dovish Fed, has strengthened markedly since the beginning of this month. The dollar index, a gauge of the greenback’s performance against a basket of other currencies, has enjoyed its longest winning streak in two years.

This is because the US, although showing signs of slowing, is still in a stronger position than the world’s other leading economies. The Fed may have turned dovish, but it is China and Europe that are the epicentre of the slowdown, benefiting the greenback.

Still, divergences in global monetary policy have narrowed markedly over the past several weeks. As the clamour for more forceful stimulus measures in China intensifies, it is the degree of dovishness on the part of Fed and, in particular, the ECB which is now the focal point of speculation among investors.

Nicholas Spiro is a partner at Lauressa Advisory