China knows artificial intelligence is rewriting the geopolitical rules, but the rest of the world looks unprepared

- Power is being redefined by data, leaving states unprepared for the global consequences of the AI revolution and individuals vulnerable to new techniques of control

In October 2017, President Xi Jinping laid out a bold plan at the Communist Party’s 19th National Party Congress, citing artificial intelligence, big data and the internet as central technologies that would transform China into an advanced economy over the coming decades.

It was the crystallisation of an ambitious strategy, in part triggered by the collective trauma endured on May 27 of that year when the AI system AlphaGo triumphed over Chinese Go master Ke Jie.

As Kai-Fu Lee writes in AI Superpowers: China, Silicon Valley, and the New World Order, “If AlphaGo was China’s Sputnik moment, the government’s AI [p]lan was like President John F. Kennedy’s landmark speech calling for America to land a man on the moon.”

Beijing had now decisively upped the stakes: theirs was the pursuit of a new vision of the future, one in which China would strive to be the global leader in AI by 2030.

Lee, the CEO of venture-capital fund Sinovation, believes China will succeed thanks to an edge in the four factors that AI success hinges upon: brains, capital, regulation and data.

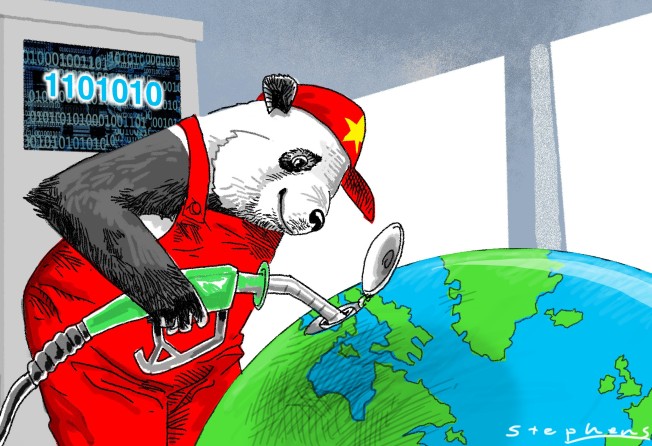

His thesis appears persuasive when you consider that China’s digital economy already generates massive pools of data, largely due to apps like Tencent’s WeChat, which integrates messaging, social media, retail and mobile payments all into one platform. So much so that The Economist saw fit to christen Beijing the “Saudi Arabia of data”.

At the city level, officials like Tianjin Vice-Mayor Sun Wenkui are splurging on AI start-ups.

The megacity of Xiongan accommodates self-driving cars. Silicon Valley’s R&D-innovation advantage is not nearly as decisive as implementation and deployment – getting algorithms to function on an everyday level – something China has been remarkably efficient in, allowing it to foster a more AI-friendly infrastructure.

Indeed, the use of big data to drive AI and machine learning is set to transform the way people live and how economies function. As the new phase of the digital revolution dawns, its arc is simultaneously pregnant with the horizon of techno-utopianism and “The Great Firewall”.

Technology’s dual-purpose potential can be wielded as a tool of control with profound consequences. Chinese authorities have already begun exploiting facial-recognition and social credit ratings to regulate public behaviour.

In India, WhatsApp has been at the centre of viral “fake news” and hoaxes that motivated a spate of mob lynchings. The rapid spread of Facebook dark ads, troll farms, Twitter bots and fake news sites resulted in a contagion that plagued the 2016 Brexit referendum and US elections.

Meanwhile, the Syrian conflict has been a laboratory for churning out a deluge of disinformation and propaganda.

With the acceleration of “platform capitalism”, power now accrues from controlling and mining data that in turn influences behaviour to produce favourable outcomes – be it economic, political or social.

This compulsion towards accumulating data intersects with the logic of surveillance; for, if data is the oil of the digital economy, then capitalist competition will encourage data extraction at the cost of privacy.

Both governments and multilateral organisations will have to weave regulatory frameworks, industrial policies and ethics into a unified AI national strategy.

What this means for geopolitics is significant: as AI blurs the boundaries between human and machine, its impact will not only be on our governance, growth models and behaviour, but the very spaces defined by our decision-making.

The evolution of human ecosystems (be it space, geospace and now cyberspace) is one that reflects a shifting balance of political power. Given machine and deep-learning, the notion of sovereignty will have to be re-evaluated.

It will be essential to understand the nexus between a nation’s digital infrastructure and capital, AI trends and geopolitics.

The unequal distribution of technology across geospatial realms will invariably disrupt the process by which countries develop, thereby critically determining their trajectories.

The international system has so far failed to construct a new social contract to ensure innovation is aligned with global governance standards.

One example of an imminent risk is deepfake videos, uses AI in programs such as FakeApp to replace filmed subjects with other people.

It isn’t hard to envision a scenario where such software is conceivably applied to simulate false portrayals of public officials, non-existent cyberattacks or biochemical epidemics that domestically and globally escalate.

Such an unsettling glimpse has all the trappings of a Black Mirror episode.

The global resurgence of nationalist agendas mean multilateral approaches bear little value on what might be considered lucrative technologies.

The grand theatre of a “cyber race”, where states compete for global data to fuel their hegemonic aspirations, seems imminent. Cyber-colonisation would become the rule, as powerful nations harness AI and biotech to administer other nations’ populations and ecosystems.

The vision of that future seems to be in motion. Of the US$15.2 billion invested in global AI start-ups in 2017, the US and China alone accounted for 48 per cent and 38 per cent of equity funding respectively.

As the two nations are engulfed in a trade war that steers them towards competitive isolation, some observers anticipate a cold war 2.0 arising: rival security blocs pegged to techno-political models that compete to offer developing economies the digital investment they will need in return for data.

If Silicon Valley falters, the algorithmic future is likely to be strung with Chinese fibre optic cables, Baidu’s driverless cars and Huawei’s mobile networks.

Amar Diwakar is a freelance writer and researcher of international affairs and political economy, focused on the Persian Gulf, South Asia, and the Belt and Road Initiative. He holds an MSc in international politics from SOAS, University of London