China’s ban on rare earths didn’t work on Japan and won’t work in the trade war with the US

- China is the world’s biggest producer of rare earths but doesn’t have the monopoly on them

- After Beijing briefly weaponised them against Tokyo, the Japanese built their own supply chain. China should not use them again, against the US

China has made no secret of its intention to weaponise the strategic market it dominates to retaliate against the US for the Trump administration’s decision to cut off telecoms giant Huawei’s supplies of microchips and components.

The state media and officials have joined a chorus of threats to block exports of rare earths to the US as a counterstrike in the spiralling trade war, with Global Times saying the minerals that the US relies on are “an ace in Beijing’s hand”.

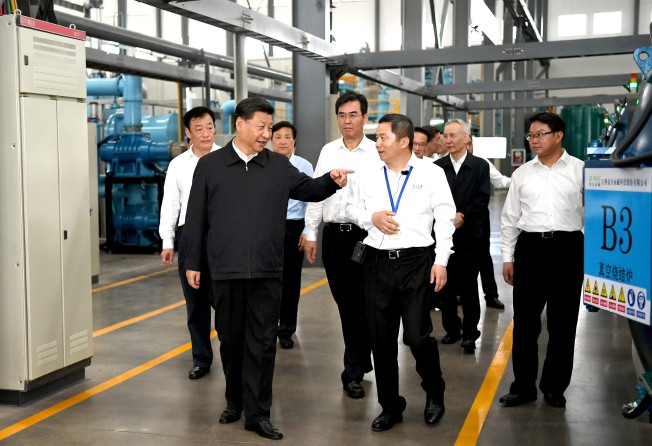

President Xi Jinping reinforced such a possibility when he visited a rare earth processing firm in Jiangxi province, following his US counterpart Donald Trump’s move against Huawei. The state media, well aware of the destructiveness of such a counter-attack, have indicated that China is prepared to fight the trade war with the US to the bitter end.

Rare earth metals, a suite of 17 elements, are crucial to important technological applications ranging from electric cars and smartphones to satellites, lasers, fighter jet engines and missiles. Indeed, they are so strategically significant that the world might be set back a few decades technologically if access to the elements is suddenly denied.

However, rare earths are actually “moderately abundant” in nature, according to the United States Geological Survey. They are rare because they occur in chemical compounds and it is costly and environmentally risky to process them into industrial materials.

A Chinese export ban would hurt some US companies, as 80 per cent of the rare earths imported by the US are from China. But the economic impact would be modest: last year, the US imported about 10,000 tonnes of rare earth compounds and metals worth US$160 million, or only 0.001 per cent of its gross domestic product.

In the event of China withholding rare earths, the US has private and public stockpiles to fall back on in the short term. In the medium term, the US and others are likely to increase their own production of rare earth metals.

China is the world’s biggest producer of rare earths, but it does not have the monopoly on them. It is estimated to have up to 37 per cent of the world’s rare earth reserves. The US also has rich deposits of the elements, and so do nations friendly to the US, such as Australia, Canada, India, South Africa and Brazil.

The US Defence Department said last week that it is looking to reduce its reliance on Chinese rare earth metals. Last year, Japanese researchers said they found rare earth deposits equivalent to hundreds of years of global consumption near the island of Minami-Torishima.

Beijing had briefly used rare earths as a weapon against Tokyo in 2010, in a territorial dispute, but it was a misfire. The Japanese responded by building a rare earth supply chain outside China, and the Chinese share of rare earth production dropped from more than 95 per cent of the world’s supply in 2010 to around 70 per cent in 2018.

The Chinese action was condemned by the US, the European Union and Japan; the World Trade Organisation also determined that the Chinese had violated global trade rules.

As the US and Chinese economies are closely intertwined in the global supply chain, any retaliation will bring more pain than gain for both parties. Bear in mind that both economies have their own vulnerabilities: the weaponisation of rare earths would hurt Chinese companies, just as the ban on Huawei is hurting US suppliers.

Worse, China is in danger of fuelling a weaponisation race, which it might not win. In this regard, the US dominates many industries and has more potential weapons in its arsenal.

A weaponisation of rare earths would also severely undermine Beijing’s efforts in recent years to play the role of a responsible actor on the global stage.

In a worst-case scenario, the sabre-rattling between the world’s biggest economic and political powers might push the world back to the bad old days of the cold-war era.

Cary Huang is a veteran China affairs columnist, having written on this topic since the early 1990s