US-China trade war is pushing the world economy closer to the edge. The longer it goes on, the harder it will be to undo the damage

- Compared to pre-2008 crisis levels, world economic growth has plummeted by half and is at risk of a long-term, hard-to-reverse stagnation. Returning to global integration and multilateral reconciliation could dramatically change the scenario

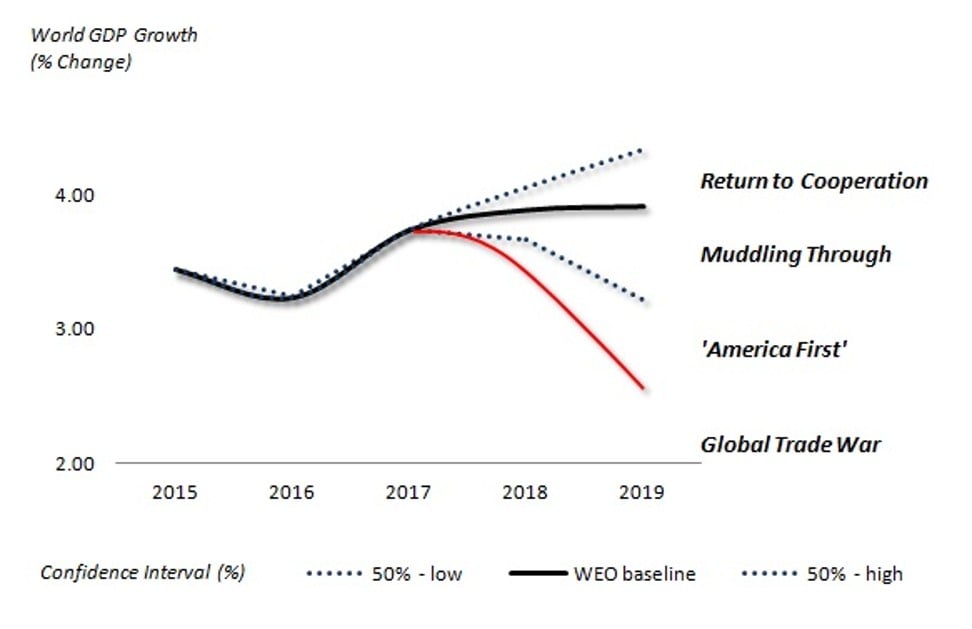

I have been following four generic scenarios on the prospects of global economic growth since the 2016 US presidential election. The first two represent variants of economic “recoupling”. In these cases, global integration prevails, despite tensions. In the next two scenarios, global integration fails, either in part and regionally, or fully and globally.

What should worry us all is that, as US-China trade war tensions have grown, global growth prospects have slowly but surely moved from the ideal and preferable scenarios towards the worst and darkest.

In the first scenario, a return to cooperation, the US and China achieve a trade agreement. Both agree to phase out additional tariffs, renounce trade threats and establish working groups to defuse other friction areas in intellectual property rights, social and political issues, and military matters.

Global growth prospects could — in the best scenario — exceed the old baselines of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development or the International Monetary Fund, at more than 4 per cent.

This was always the least likely scenario and, today, its probability is minimal. Yet, it is important to remember that around the time of the first meeting in 2017 between US President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping, many observers saw the scenario as possible, even probable.

In the second scenario of muddling through, the tariffs’ economic impact is limited to 0.4 per cent of China’s economy and 0.8 per cent for the US. During the truce, the US and China develop a path to a trade agreement but other friction areas, particularly in advanced technology, result in new skirmishes.

Uncertainty decreases but fluctuates. Global economic prospects barely improve. Markets witness rallies and plunges. Global recovery fails. Global growth prospects remain close to 3.5-3.9 per cent. Only half a year ago, this scenario was still seen as viable. Today, it feels like a bygone world.

In the third, America First, scenario, the import value at stake is tenfold relative to the start of the trade war, amounting to more than US$500 billion, with soaring collateral damage. In China, it could shave 0.4 per cent off economic growth this year and, in the US, 0.8 per cent. Neither the US nor China agree to phase out additional tariffs. Talks linger, fail or lead to new friction.

Uncertainty increases, volatility returns. Global prospects decline further. Markets linger at the depths. In this scenario, global prospects dampen as world economic growth in 2019 sinks to 3 per cent or worse.

Finally, in the scenario of a global trade war, all bets are off. The US and China fail to agree on a compromise. Additional tariffs are enacted and new trade threats declared. The White House escalates attacks against Chinese industries, taking aim at intellectual property rights, social and political issues, and military modernisation. Volatility soars. Real economic growth in the US takes a severe hit. Chinese growth erodes.

Eventually, risks to the global outlook overshadow world economic growth, which could linger at 2-2.5 per cent or worse. World trade and investment plunges. Migration crises abound. The number of globally displaced, which has exceeded World War II figures since the mid-2010s, soars to record highs. A series of new geopolitical conflicts prove harder to contain.

So, where are we today with regard to these scenarios? A simple answer is: moving closer to the edge. After trade frictions and the Trump tariffs undermined the momentum of global recovery, the International Monetary Fund finally woke up to the effects and started predicting that global economic activity will slow notably.

In early June, the World Bank estimated the world economy would expand by only 2.6 per cent. The IMF has also warned that trade wars could wipe US$455 billion off the world’s gross domestic product in 2020. Worse, Trump increased tariffs on US$200 billion worth of Chinese goods exported to the US, and introduced an effective ban on American companies doing business with Chinese telecom giant Huawei Technologies in May.

In brief, the status quo is shifting from the America First scenario towards an all-out global trade war.

In effect, multilateral banks’ estimates are still downplaying the collateral damage. If the Trump administration continues to expand trade wars and geopolitical ploys in multiple regions, their models ignore the impending adverse feedback of such measures — as evidenced by Morgan Stanley’s business conditions index that just took the worst one-month hit in its history.

To understand how much expectations have been revised, recall that before the 2008 crisis, the global growth rate was 4-4.3 per cent. The current rate has almost halved from its pre-crisis level. Something similar occurred in the 1970s, which saw the end of the “glorious 30” — three decades of solid post-war growth in major advanced economies.

What we are witnessing now is a potentially fatal fall into long-term stagnation. In part, it is structural, resulting from maturing economies and ageing populations. But, in part, it is self-induced and the effect of misguided trade policies and unilateral geopolitical aggression. In the absence of tariff wars and geopolitical destabilisation, the global growth rate could now be closer to 3.5 per cent.

The longer it takes to achieve multilateral reconciliation, the more likely it is that falling long-term growth rates will prove harder to reverse.

Dr Dan Steinbock is the founder of Difference Group and has served at the India, China and America Institute (US), Shanghai Institute for International Studies (China) and the EU Centre (Singapore). See http://www.differencegroup.net/