How Hong Kong protesters are turning off their mainland Chinese supporters

- With Tiananmen in recent memory, even the most liberal-minded mainland Chinese find violence as a means to an end hard to accept

- With Hong Kong protests becoming more disruptive and radical, and xenophobic slurs more prominent, support is waning among former sympathisers

On June 16, I shared on my social media feeds a clip of thousands of Hong Kong demonstrators moving aside in seconds to allow an ambulance to pass, amid a two-million-person march against a controversial bill that would allow the extradition of suspects to the mainland. “It’s like Moses parting the Red Sea, so moving,” I wrote.

Many friends of mine who are originally from mainland China also expressed their admiration of the courageous protesters. These friends are well-educated, informed, and critical of authoritarianism.

More than two months later, with radicalisation and violence tarnishing the movement, many are now having second thoughts. In mid-August, seeing the chaos at Hong Kong airport when protesters blocked travellers from boarding their flights and assaulted two mainland individuals suspected of being “undercover policemen”, these initially sympathetic friends expressed their disappointment.

For Richard, a Cantonese-speaking Guangzhou native who received his master’s degree in the United States and has worked in Hong Kong for nearly 10 years, the turning point was July 1, when protesters smashed the glass doors of the Legislative Council and vandalised it. “I don’t understand why people who claim to value democracy would ruin one of the most important democratic institutions that fulfils the separation of powers. It’s good for nothing except venting.”

Lewis, a Silicon Valley engineering manager born in Hangzhou, also started to doubt the demonstrators’ tactics after watching those scenes. What he found especially objectionable was the way some opponents of the movement had been treated.

“Even though Hong Kong has more or less lost some freedoms it once enjoyed, by and large the society is still a free one, and the government is not nearly as authoritarian as that in Beijing; endless street confrontations with no end in sight aren’t justified,'” he added.

Muzi, a young Washington DC teacher originally from northeastern China, recently quarrelled with her Hong Kong-American husband. She does not buy the accusations of widespread police brutality. “When it comes to violence like arson, Molotov cocktails and jumping on officers, how would the police in the US react? Probably with real bullets. So far, no fatal casualty, and the Hong Kong police have refrained from using riot control methods more lethal than things like tear gas, while they and their families have become targets of violence, doxxing and death threats.”

She was especially furious that two mainlanders were beaten up and humiliated at the airport. “Quite a lot of Hongkongers are hostile towards mainlanders. When I spoke Mandarin in some Hong Kong stores, the young shoppers were unfriendly to me. And it’s not just me. That kind of thing hurts.”

And for the Xi’an born, Singapore-based financial industry professional James Liu, the turning point was when the MTR and airport operations were targeted.

He thought it ironic that supposedly freedom-loving protesters would block train doors and airport check-in counters, showing little consideration for people who might have jobs to do, schedules to keep or homes to go back to, including pregnant women, crying children and the elderly in wheelchairs. “One’s freedom shouldn’t be exercised at the expense of that of others. Irrational radicalisation always leads to disasters.”

These friends of mine are by no means pro-Beijing. They had all shared Hongkongers’ frustration over the national authorities’ encroachment on political freedom in the territory. What has made them critical of the protests?

For one thing, most of my liberal-minded peers who grew up on the mainland find violence hard to accept, and the ends justifying the means hard to stomach, mainly due to either their or their parents’ life experiences through the tumultuous years in China’s history.

The highly decentralised protests in Hong Kong have been leaderless and fluid“like water”. Among the participants, there is apparently a code of conduct – stick together and never disavow each other no matter what. Thus, so far, prominent participants in this movement have yet to come out to forcefully condemn those responsible for vandalism and violence.

This “people using violence and condoning violence always together” signature, unfortunately ties the movement to the horrible actions of a few. When actions became increasingly radicalised, the initially sympathetic mainlanders drew a line between what is acceptable and what it is not.

Secondly, to many mainland people, the wounds of Tiananmen are still fresh. With the benefit of hindsight, they wish that the modern political practice of give-and-take had had a chance to take root and avert the bloody crackdown. And they have a really hard time understanding the apparent willingness of the protesters to take the city down and ruin everybody on board if their demands are not completely satisfied.

Furthermore, over the past two months, the rift between the mainland and Hong Kong has widened significantly. More young Hongkongers are less inclined to see the Beijing authorities as different from ordinary mainlanders. Nativism is on the rise and their northern neighbours have experienced hostility. Slurs on mainlanders such as “locusts” and “savages” can be heard often. Many mainlanders initially sympathetic to Hong Kong have been offended by the open display of xenophobic sentiments, especially the derogatory “shina” seen in graffiti.

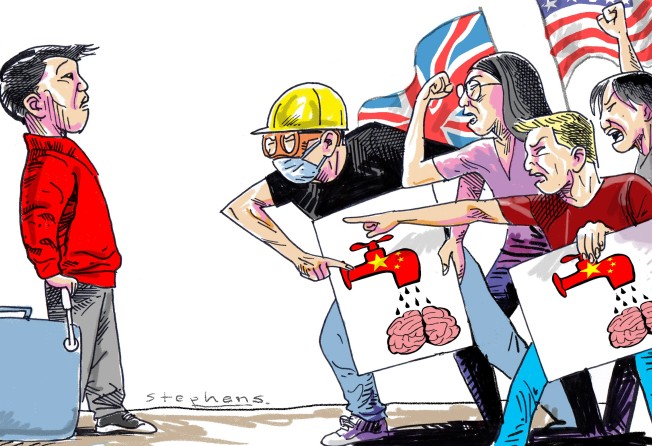

Sadly, each side now holds stereotypical perceptions about the other. Many mainlanders dismiss the UK/US flag-waving Hongkongers as people uncomfortable with the decline of Hong Kong’s geopolitical and economic status, and many mainlanders’ nationalist mindset makes them hostile to any political activity challenging the central power – thus, “pro-independence” separatism.

Hongkongers, on the other hand, have a tendency to paint mainlanders and overseas Chinese who do not totally agree with them as “brainwashed nefarious slaves” of the Communist Party and enemies of democracy.

For a few days, peaceful protests returned to Hong Kong, but soon, so did chaos, violence and vandalism, with shops smashed by some anti-government protesters.

I can only hope that, before long, the goodwill we once felt on the night of June 16 can return for good, and a tragedy like that experienced 30 years ago can be avoided.

Audrey Jiajia Li is a nonfiction writer and broadcast journalist