In a critical hour for Hong Kong, universities can help us find our way back to humanity

- Universities play an increasingly economic role in society but, more importantly, they should be places of thinking. In a polarised Hong Kong, it is the study of humanities that will equip people with critical thinking skills and empathy

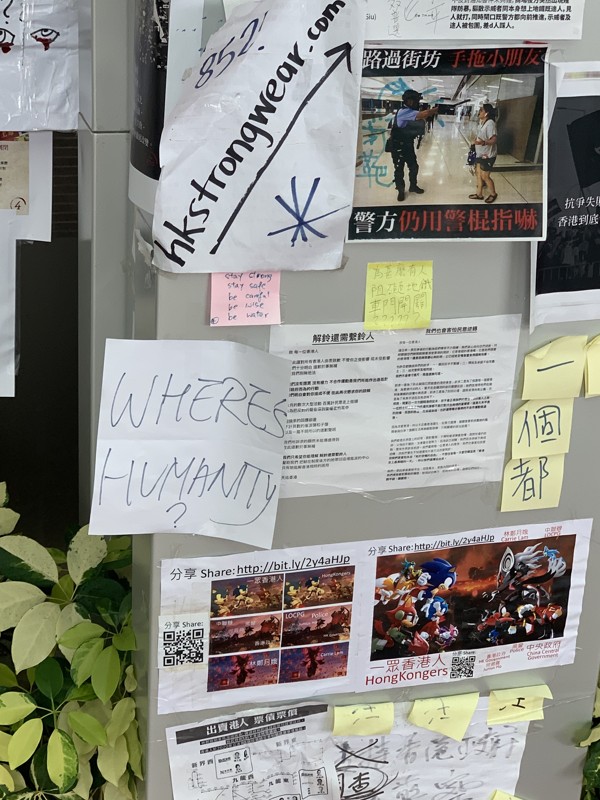

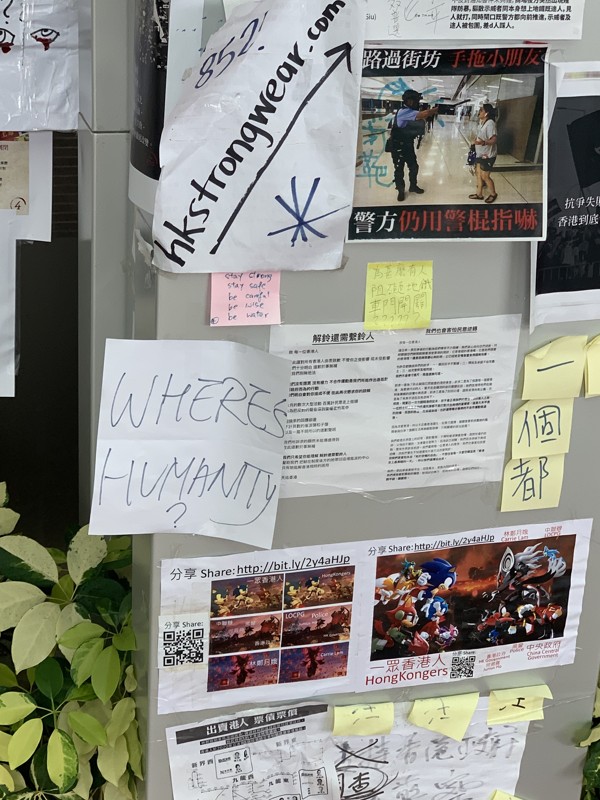

On the first day of the new academic year, the campus of the University of Hong Kong was as glum as a washed out holiday. Yes, there were students in the classrooms, but there was none of that first-day-of-semester camaraderie that usually animates the corridors. The jumble of anti-government posters stuck up on the walls looked utterly forlorn, a hopeless cri de coeur.

Ostensibly, it’s business as usual, despite the proposed class boycott. The university’s senior management has reiterated its pledge to uphold the institution’s core values. As President and Vice-Chancellor Xiang Zhang told all staff and students recently: “HKU forms a key part of the wider community, and is deeply invested in everything that takes place in our city.”

Along with many of my fellow academics, I have followed the intensifying violence between police and anti-extradition protesters with dismay. After all, the young protesters whose bloodied faces now circulate through the global media could well be our students. Some of them probably are.

And it’s impossible to reconcile our own experience of Hong Kong’s courteous youth with the increasingly censorious local news coverage that lumps young protesters together indiscriminately as “radicals” and “criminal elements”.

Anyone who has taught at a Hong Kong university can attest to the conscientiousness, consideration and impeccable manners of the student body. If there were Times Higher World University Rankings for student politesse, Hong Kong would be at the very top, no contest.

And, as with many of my colleagues, the escalating violence – much of it directed at young protesters – has elicited in me mixed emotions of shock, sadness and exasperation at the government’s political failure to find a solution. As a professor in the School of Humanities, events have also prompted deeper reflection about the field I research and teach in: the humanities.

As a poster I recently spotted on the students’ anti-government wall at HKU expressed it, “Where’s Humanity?” A good question and one that ought to jolt all humanist academics, like me, as they hurry to their classes.

Beyond this is a question that, at least in my view, all universities in the city ought to be addressing with some urgency at this point. Bluntly: what are universities for?

Since the neoliberal, free-market onslaught of the 1980s, universities have increasingly justified their existence on economic grounds. An output-impact model that favoured the applied sciences, medicine and technology has extended across the campus. In the process, the arts and humanities have invariably been sidelined, forced to play second fiddle to the big beasts who bring in the big funding.

Of course, universities ought to and do play a major economic role in society. As catalysts for technological innovation and engines driving professional expertise and public service, they can clearly benefit the broader community in a myriad of ways.

But they have another important role to play, as well. They are places of thinking.

In a well-known formulation, philosopher Martin Heidegger wrote that “science does not think”. This doesn’t mean that science is unthinking (far from it), only that science doesn’t need to self-reflect, as the humanities do, because it can make things happen. In this sense, its purpose is self-evident.

The humanities, on the other hand, are in the business of thinking. They provide critical perspectives on the world, examining how and why the world is as it is, and how and why it might be different. Thinking of this kind fosters empathy and lays the ethical groundwork for the doings of science and technology, the fundamental link between knowledge and good practice.

Today, as tensions mount across Hong Kong, it is imperative that residents maintain the right and ability to think and speak freely, and that they resist any form of encroaching self-censorship. This is a life-and-death matter for the city’s universities as spaces of independent inquiry.

The humanities require freedom. Of course, thinking can happen in times of non-freedom, which, after all, has characterised much of human history. But, as an institutional capacity and social practice, thinking becomes impossible without freedom. Indeed, the humanities are a barometer of freedom, the proverbial canary in the coal mine.

Which is why, as Hong Kong society becomes increasingly polarised, with people on every side reduced to ciphers, there’s a pressing need to reassert the human in humanities. We owe it to our students.

Robert Peckham is MB Lee Professor in the Humanities and Medicine at the University of Hong Kong