After the 1967 summer of discontent, Murray MacLehose led the crusade for a happy and prosperous Hong Kong. Where is that spirit today?

- Housing, education, medical care and social welfare: the issues addressed by the governor in the wake of the 1967 unrest are again front and centre in Hong Kong’s latest summer of discontent. Will the government take a leaf out of MacLehose’s book?

The Hong Kong government is besieged by its own citizens. Clouds of tear gas drift above streets that convulse with angry demonstrators, as police and radical protesters clash amid flames and gunfire. Blood splatters the pavement as pro-China and pro-Hong-Kong factions brawl. There are ominous rumblings of Chinese forces gathering across the border. The future of Hong Kong, in the eyes of its people and the world, is bleak and uncertain.

Just another weekend in 2019’s long, hot summer of discontent? The description is apt, but it was equally fitting during Hong Kong’s summer of unrest in 1967. The parallels are striking. Five decades ago, it took leadership that committed to real solutions to social problems, not political problems, to right Hong Kong’s ship.

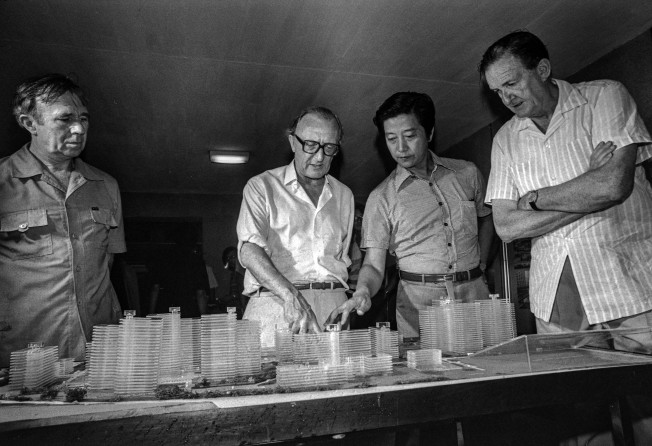

It took the arrival of an action-oriented leader of social change, Murray MacLehose, governor of Hong Kong from 1971 to 1982. Affectionately known as “Murray-in-a-Hurry”, MacLehose would later describe his mission in Hong Kong in simple terms: “My job was to make Hong Kong as contented and prosperous and cohesive as possible.”

Hongkongers are victims of their own laissez-faire system and a non-interventionist, administratively focused local government, not the machinations of the Chinese state. Hong Kong’s leaders, or their successors, need to take a page out of MacLehose’s book and take up the crusade for people’s contentment and prosperity.

Although political issues dominate headlines and public debate, much of the discontent can be traced to the reality of day-to-day life. The proportion of people living below the poverty line was 20 per cent in 2017, according to government statistics. That is 1.3 million people.

This goes some way to explaining why millions have taken to the streets in recent months. Unemployment is low, at less than 3 per cent, but for most who work in this famously hardworking city, it is their low income relative to Hong Kong's high costs that makes getting ahead virtually impossible.

This year, Hong Kong topped the Mercer Cost of Living Survey as the most expensive city in the world to live in. Housing affordability is particularly dire. Midland Realty, a local property brokerage, calculated that it takes 61 per cent of household income to afford a 500 sq ft flat financed with a 70 per cent mortgage.

That leaves little for food or other necessities. With the average property costing the equivalent of US$1.2 million, the possibility of somehow assembling a 30 per cent down payment to buy a flat is remote, particularly for a young person. Public rental housing programmes exist, but the waiting period, according to the Housing Authority, is 5 years five months.

Income disparity is extreme, not surprising in a system tilted to high-income earners and the wealthy, where personal income tax rates top out at only 17 per cent, and many forms of investment returns, such as capital gains, interest and dividends, attract no tax at all.

According to Oxfam, the 2016 Gini coefficient for post-tax, post-social-transfer monthly household income for Hong Kong was 0.473, one of the highest levels of inequality in the developed world, and substantially higher than comparable places such as Singapore at 0.356, Britain at 0.351, and the US at 0.391.

While Hong Kong is perennially ranked as the freest economy in the world by US think tank the Heritage Foundation, today’s unrest is exposing the limits of unfettered markets and passive government, much as the imbalances in the colony’s society were exposed in 1967. As governor MacLehose did then, the Hong Kong government needs to address the prosperity of the greater part of its citizens.

Fortunately, the government is comparatively rich, with fiscal reserves recently at HK$1.14 trillion (US$145 billion). Conservative budgeting that results in surpluses year after year should be rethought.

When MacLehose was implementing his vision to change the prospects of the people of Hong Kong in the early 1970s to the early 1980s, he raised government expenditure as a percentage of gross domestic product by 38 per cent, a resultant eight times increase in expenditure in US dollar terms.

His unprecedented social programmes tackled housing, education, medical care and social welfare, and put Hong Kong on track for the prosperity that followed.

In the years following the 1997 handover, Hong Kong’s government has been too obsessed with managing its sensitive political relationship with Beijing. The extradition bill was but one manifestation of this.

This distraction has prevented them from giving serious attention and resources to improving the social conditions and prospects of citizens. Issues of democracy and freedom will not fall off the agenda, but after 22 years of being part of China, it is time for a more visionary, public-welfare-oriented approach to governance.

As for whether Beijing might support this, Hong Kong’s leaders need only look to one of the 14 points of Xi Jinping Thought which declares that: “Improving people's livelihood and well-being is the primary goal of development.” Governor MacLehose would no doubt have agreed.

Robin Hibberd was executive vice-president of Scotiabank (a large Canadian-based international bank) until 2015, managing Scotiabank in Hong Kong, Greater China and also its Asian region. He has lived in Hong Kong since 1993 and is a former president of the Canadian Chamber of Commerce in Hong Kong