To gauge France’s South China Sea intentions, look at what it does, not what it does not say

- With his China visit, French President Macron won trade deals and climate cooperation and shored up European Union interests

- His silence on the South China Sea, however, does not mean France will stop trying to curb China’s influence or end arms sales to its rivals

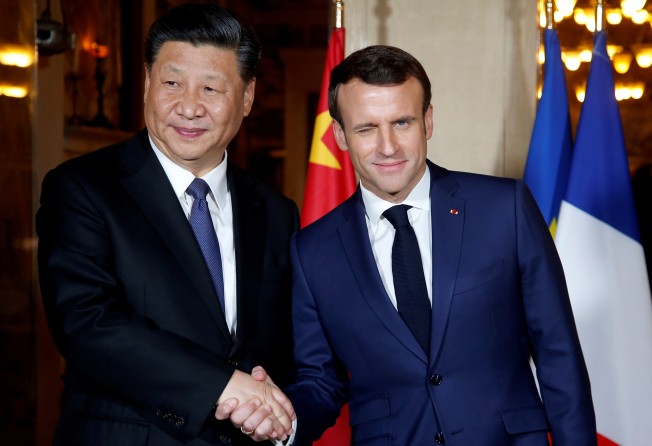

As he scrambled to help French businesses win lucrative contracts and protect the European Union’s commercial interests ahead of a possible solution to the trade war between China and the United States, President Emmanuel Macron of France was careful not to publicly raise objections to Chinese policy in the South China Sea during his recent trip to Shanghai and Beijing.

Unsurprisingly, a French declaration released at the end of Macron’s meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping on November 6 made no mention of the contested waters.

The Chinese had warned the French president not to touch upon the issue. Zhu Jing, deputy director of European affairs at the Chinese foreign ministry, said on November 5 that France should not play “a disruptive” role in the Indo-Pacific or send warships into Beijing-claimed territorial waters.

But France has toughened rhetoric against China’s moves in the South China Sea in recent years, and are playing a game east of Suez that basically matches the US Indo-Pacific strategy – a euphemism for containment of China.

The French navy deploys assets in the South China Sea an average of three to four times a year. China says it has historical rights to vast swathes of the resource-rich area, which is also a vital shipping route, but Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei and the Philippines dispute such claims.

France also sent the frigate Vendémiaire to the sensitive Taiwan Strait in April, leading to Chinese protests. Paris replied that its vessels would regularly sail in the region to reaffirm commitment to international maritime law.

For French officials, their country’s naval presence from the Arabian Sea to the Pacific Rim is aimed at preserving open seas, asserting freedom of navigation and securing the respect of international rules.

French defence minister Florence Parly said in the official policy document “France and Security in the Indo-Pacific” that the Indo-Pacific remains “an area of tensions due to the challenging behaviour of some states with regard to United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea”. The document added: “In the South China Sea, the large-scale land reclamation activities and the militarisation of contested archipelagos have changed the status quo and increased tensions.”

The French clearly refer to China’s expanded military footprint in the China seas. During a hearing before the French National Assembly in July, Chief of Staff of the French navy Christophe Prazuck said China’s ambitions extends to the Indian Ocean. He insisted that Chinese actions in the South China Sea called into question international maritime law and arbitration rulings.

France considers itself a resident power in the Indo-Pacific, where it has overseas dependencies and vast exclusive economic zones. It has restarted the Indo-Pacific Security Dialogue with the US, which in turn welcomed the extended deployment of the Charles de Gaulle aircraft carrier to the Indo-Pacific this year. Washington and Paris also share an emphasis on building a network of strategic alliances and partnerships to maintain a free and open Indo-Pacific.

Admiral Prazuck last month proposed joint patrols in Indo-Pacific waters between the navies of France and Australia – Canberra is increasingly at odds with China over its geopolitical assertiveness in the South China Sea and the South Pacific.

In Prazuck’s view, Australian warships could also contribute to escorting the Charles De Gaulle carrier when it conducts operations in the region, while French frigates could escort Australian amphibious ships. The French want greater interoperability with the Australian military, particularly in the realms of amphibious landings and anti-submarine warfare.

The Charles de Gaulle carrier trained in the Bay of Bengal with Japanese, Australian and American warships in May this year. Later, it conducted anti-submarine warfare drills with the Indian navy during the annual Varuna exercise, which was likely to have had China in its sights, and ended its Indo-Pacific mission in Singapore.

Common operations with the US Coast Guard, which has had a continued presence in the Western Pacific this year, and already has experience working with French naval forces in the South Pacific, would raise the French security profile in the South China Sea.

However, France must balance conflicting interests – the need to step up economic cooperation with China and, at the same time, help insulate the Western-shaped international order from Chinese challenges. This is why France carries out naval actions in the Indo-Pacific in a way that avoids irreparable damage to relations with China.

As a measure of “deconfliction”, France and China have agreed on a regular rhythm of French vessels’ stopovers in China and Chinese warships’ stopovers in France. Further, when the French warships sail between the islets of the South China Sea, they choose to stay outside the limit of territorial waters, which reduces the risk of incidents with Chinese forces.

If anything, the Chinese will eventually grow annoyed with France’s massive arms sales to China’s rivals and competitors. France reportedly sold some US$23 billion worth of weapons systems to Indo-Pacific countries between 2008 and 2017, of which US$15.5 billion were to India. Australia has increased reliance on French-manufactured weapons. South Korea, Indonesia, Singapore and Malaysia are also big purchasers of French arms.

Paris may well soften its opposition to China’s military activities in the South China Sea to protect trade ties, but it is doubtful that it will give up arming Beijing’s neighbours. Weapons sales are a pillar of France’s Indo-Pacific strategy, whether the Chinese like it or not.

Emanuele Scimia is an independent journalist and foreign affairs analyst