05:38

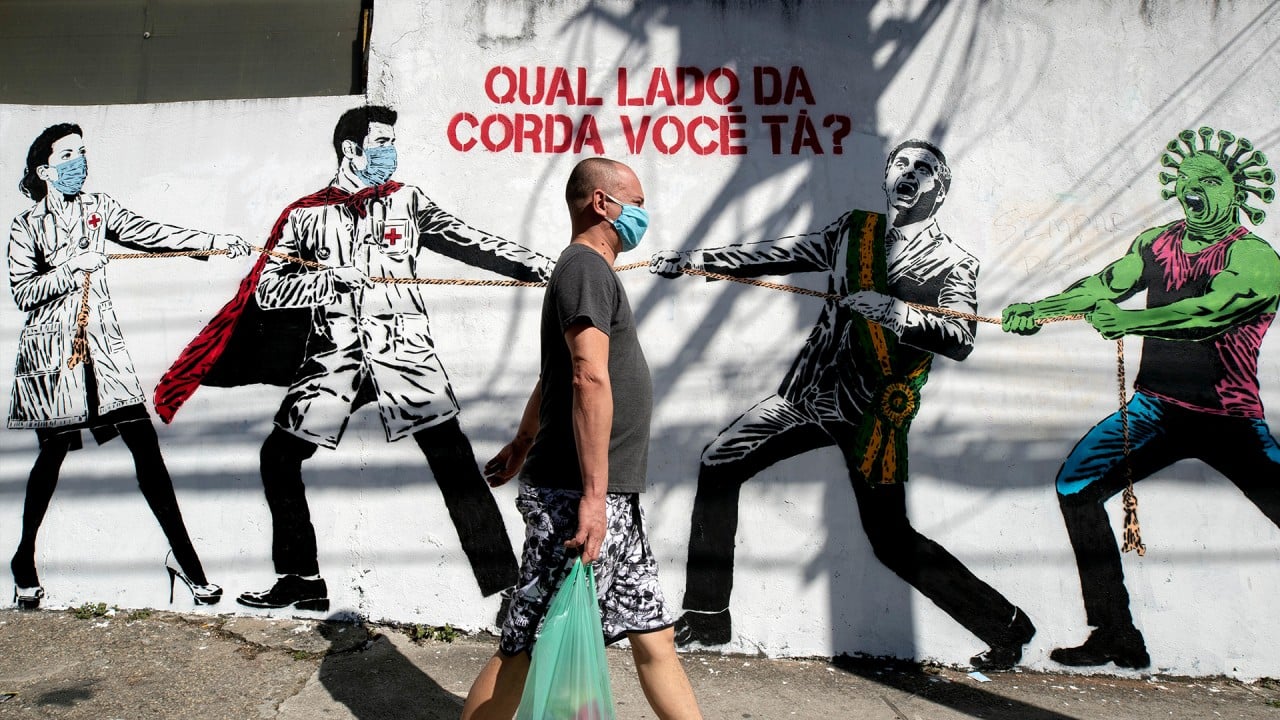

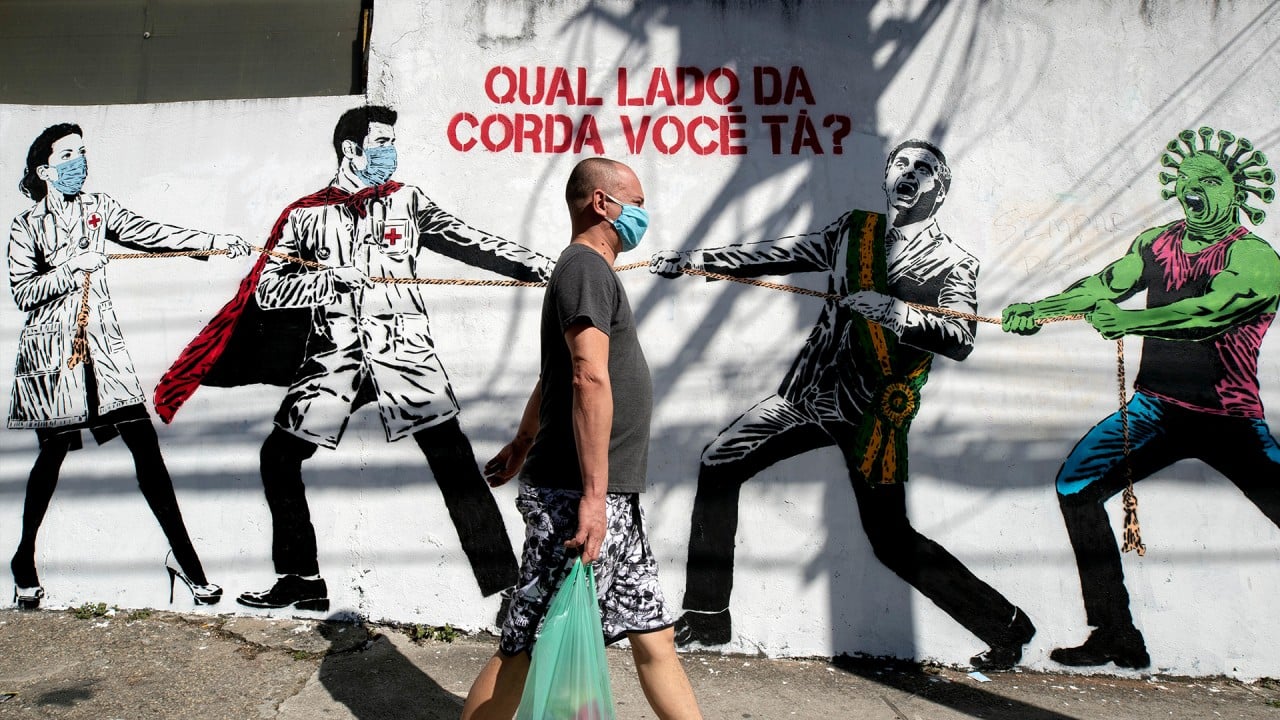

Experts reluctant to predict end of Covid-19 pandemic as global case numbers keep setting records

A comfort in these dark days of pandemic and recession has been the presence of governments and central banks with apparently bottomless purses.

Without this largesse, the world economy would be in a depression and in the midst of a savage financial crisis. But how long this fiscal and monetary support can continue if the pandemic flares up, or enters a second wave with no medical solution, is a very real risk.

We used to believe that governments had two revenue sources: taxes plus borrowings. And that central banks did not simply go on printing money. By some strange alchemy, however, debt concerns have become a thing of the past.

Governments can continue handing out trillions of dollars in aid to businesses and households while central banks prop up an increasingly shaky-looking financial system.

Meanwhile, the horror story on the economic front continues to worsen. In its latest economic outlook, the International Monetary Fund suggests the economic slump may be much longer-lived than feared and the need for propping-up measures much greater.

The figures are almost unbelievable. As IMF chief economist Rita Gopinath said, “We are now projecting deeper recession in 2020 and a slower recovery in 2021. Global growth is projected to decline by 4.9 per cent in 2020 [vs 3 per cent forecast in April] followed by partial recovery … in 2021.”

05:38

Experts reluctant to predict end of Covid-19 pandemic as global case numbers keep setting records

The country forecasts are most dismaying. The US economy is projected to shrink by a dramatic 8 per cent this year and Britain’s by 10 per cent, while Japan’s contracts by nearly 6 per cent, Germany’s shrinking by 7.8 per cent and France’s by 12.5 per cent.

Even next year’s partial recovery might not materialise in the event of a second wave. The picture looks grim too, in Asian and other emerging economies (not least India, whose economy is projected to shrink by 4.5 per cent).

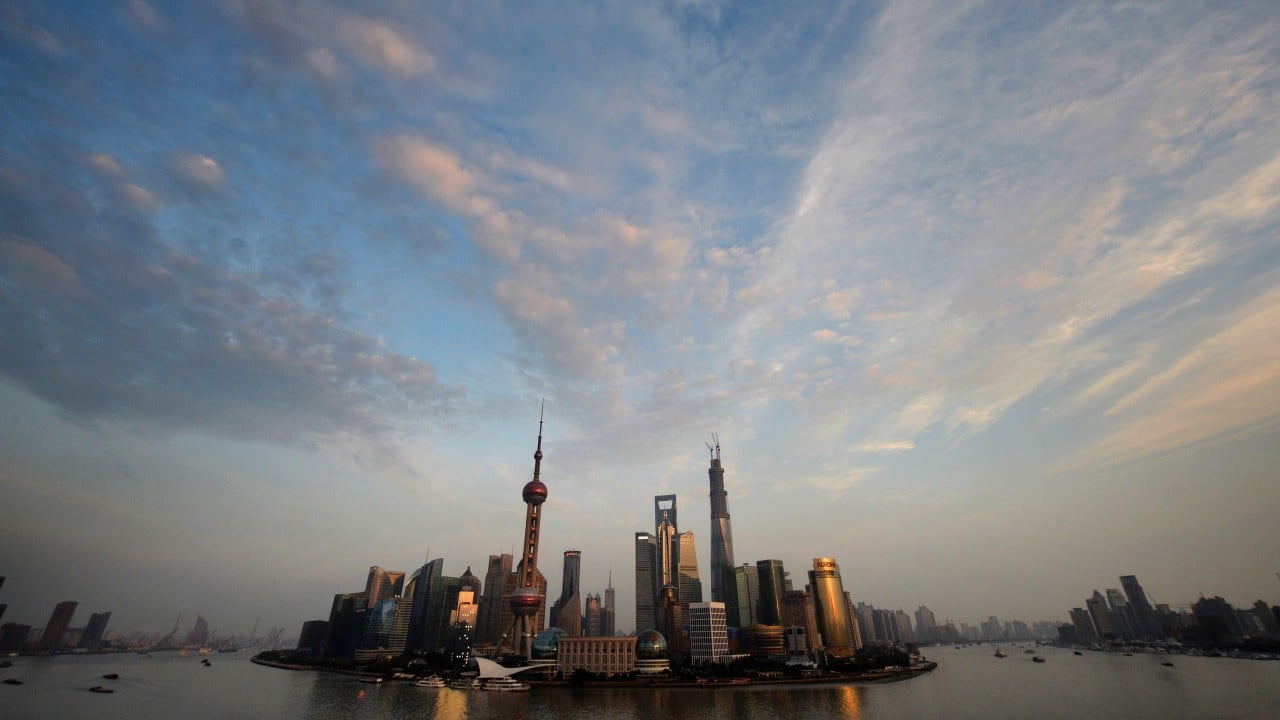

In this “synchronised slowdown”, China is the only major economy projected to grow this year but, at 1 per cent, this is not enough to pull the world out of recession, as China did after the 2008 global financial crisis.

05:59

Coronavirus: What’s going to happen to China’s economy?

The upshot is that the global economy will need a lot more policy support by way of fiscal measures (already amounting to some US$10 trillion) plus central bank purchases of financial assets to save stock markets from economic reality.

But back to the question of how long official financial support can keep coming. As Harvard economist (and former S&P Global chief) Paul Sheard wrote: “The blowout in fiscal deficits around the world triggered by the Covid-19 pandemic is leading many to ask: how are we going to pay for all this?”

He argues, however, that concern about fiscal deficits is largely outdated as “government debt issued in domestic currency never actually needs to be repaid”. He said: “We need to rethink the macroeconomic policy framework particularly the relationship between monetary and fiscal policy.”

05:55

What if Covid-19 is here to stay? Why we may need to prepare for the coronavirus becoming endemic

He added that “the size of the budget deficit should be driven by how far from full employment the economy is and how much inflationary or deflationary pressure there is, not by concerns about how much debt a government is accumulating”.

Such arguments tend to be arcane yet are so important that economists need to explain them more clearly. Finance ministers do not appear to have fully bought into them (supposing they fully understand them). Fiscal caution is still widely regarded as a virtue.

Indonesian finance minister Sri Mulyani Indrawati, for example, said at a recent Bloomberg investment event in Hong Kong that her government will do all it can to keep borrowing in check, and warned against slipping into the “habit of undisciplined fiscal and monetary stimulus”.

01:26

Indonesia coronavirus death toll may be higher than reported, burial numbers indicate

Cheah Cheng Hye, co-chairman of Value Partners Group, suggested at the same event that such behaviour could only “result in tears”. Moody’s Investors Services has said that economic slowdown will raise advanced economies’ debt burdens sharply and could result in credit rating downgrades.

With interest rates at rock bottom, leading economies can afford to finance the current debt burden but it can only get bigger. And emerging economies are running out of policy space for further fiscal stimulus, said the Institute of International Finance.

Coping with the recession is a matter of “all hands on deck” (fiscal and monetary), said the IMF’s Gopinath. But she added that this cannot extend to limitless fiscal support. Sheard, too, acknowledged the risk of high inflation if too much purchasing power is injected into an economy.

The moral for policymakers seems to be, do not rely too much on kindly uncles from finance ministries and central banks. Focus on getting the pandemic under control and then get everyone back to work, and economies back on a sustainable recovery track.

Anthony Rowley is a veteran journalist specialising in Asian economic and financial affairs