German election: why China-Germany tensions won’t be eased, whoever wins

- Germany’s election campaign has lacked a proper debate about China, despite fears its industry is losing out in trade

- Germany appears to be heading for Merkelism without Merkel, which is not necessarily good for bilateral relations

In just over a fortnight, Europe’s largest economy, and the world’s fourth-biggest, will hold a highly unpredictable election in which only two outcomes are certain.

The first is that Angela Merkel, Germany’s chancellor for the past 16 years, will step down, marking the end of an era in which Europe’s most powerful leader provided an anchor for European integration and was the most passionate defender of the West’s liberal values.

The second is that Merkel’s succession will not be smooth. Political fragmentation – different coalition permutations are possible after polling day on September 26 – makes it all but certain that the next government will lack a strong mandate for the hard decisions Germany needs to take.

That financial markets are not in the least bit concerned about the post-Merkel era – the Dax, Germany’s main equity index, is trading close to an all-time-high – might suggest a degree of complacency.

A more plausible interpretation is that the odds of Merkel’s successor charting a different course are slim. This is especially so in foreign affairs, particularly when it comes to China, a sensitive policy area given concerns over Germany industry’s dependence on an increasingly authoritarian and economically more sophisticated Middle Kingdom.

For years, German policy towards China has been guided by the principle of Wandel durch Handel – change through trade – whose strongest proponent and beneficiary has been Germany’s large carmakers and their suppliers.

A report published last November by the Mercator Institute for China Studies, a Berlin-based think tank, noted that Germany accounted for 48.5 per cent of EU exports to China in 2019, 4½ times more than France, the bloc’s second-biggest exporter to China in value terms.

Brands of Volkswagen, Europe’s largest carmaker, sold 4.2 million vehicles in China in 2019, nearly 40 per cent of the company’s passenger car sales. Several other Dax-listed firms, including BMW and chip maker Infineon, derive over one-fifth of their revenues from China.

Yet, while the world’s second-largest economy has become Germany’s biggest trading partner, it accounts for less than 8 per cent of its exports. The automotive sector’s outsize exposure is, according to the report, “a key driver of the perception that Germany and Europe are dependent on China”.

However, over the past few years, a major reassessment of Germany’s trade relationship with China has begun to exert an influence on policy. The breakdown in Sino-US relations under president Donald Trump helped bring to the fore German concerns about commercial ties with China.

In January 2019, the BDI, Germany’s main business lobby, sounded the alarm by publishing a paper calling China a “systemic competitor”. It called for a strong and united European response to the threats posed by a “state-dominated economy”, but also stressed the need for “an ambitious industrial policy for Europe and its companies”.

Fears that German industry is losing out in trade with China have intensified since the eruption of the pandemic. Chinese manufacturers’ rapid move up the value chain, allowing companies to produce more sophisticated machinery that can vie with high-quality German capital goods, has helped erode German export competitiveness.

A recent study by the Cologne Institute for Economic Research noted that the European Union is importing a growing proportion of high-end industrial goods from China, with the share of such products in the bloc’s imports surging from 50.7 per cent in 2000 to 68.2 per cent in 2019.

The pressure on German exporters has been exacerbated by the global supply chain crunch, which is aggravated by disruptions to trade caused by China’s zero-tolerance approach to Covid-19 cases. The shortage of semiconductors has hit Germany’s car industry hard, with Volkswagen’s global sales plunging 19 per cent year on year in July.

Addressing the challenge posed by China calls for a serious discussion, especially with Merkel – who has been reluctant to adopt a tougher diplomatic stance on China – about to bow out.

Yet, Germany’s election campaign has conspicuously lacked the proper debate that policy on China – and other key foreign and domestic issues – warrants. This is because the main parties’ candidates have bigger problems to contend with.

Unpopular with voters to varying degrees, and loath to call attention to their positions on sensitive subjects, all three leading contestants have barely mentioned China.

While the Greens’ candidate, Annalena Baerbock, is the most hawkish, she has performed poorly, as has Armin Laschet, the candidate for Merkel’s ruling Christian Democrats, who has paid a price for his blandness.

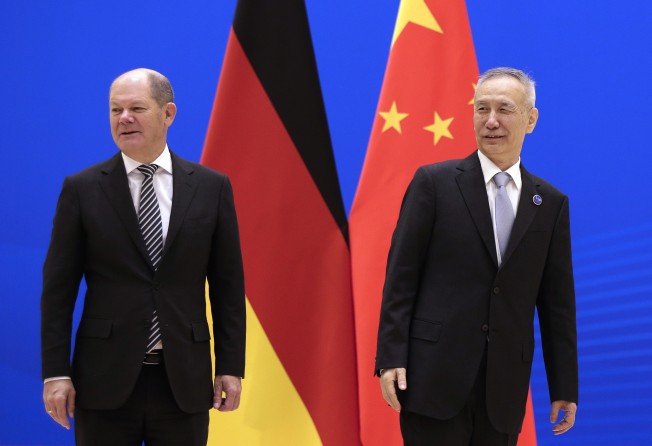

Tellingly, the candidate with the best chance of succeeding Merkel is the one who has been most successful at convincing the electorate that little would change if he heads the next government. Olaf Scholz, the Social Democrat candidate and current finance minister, has emerged as the continuity candidate.

Regardless of the outcome of the election, Germany appears to be heading for Merkelism without Merkel. This will please the nation’s powerful car industry, which has become more dependent on China, but it will not make it any easier to address the problems bedevilling Sino-German relations.

Nicholas Spiro is a partner at Lauressa Advisory