01:51

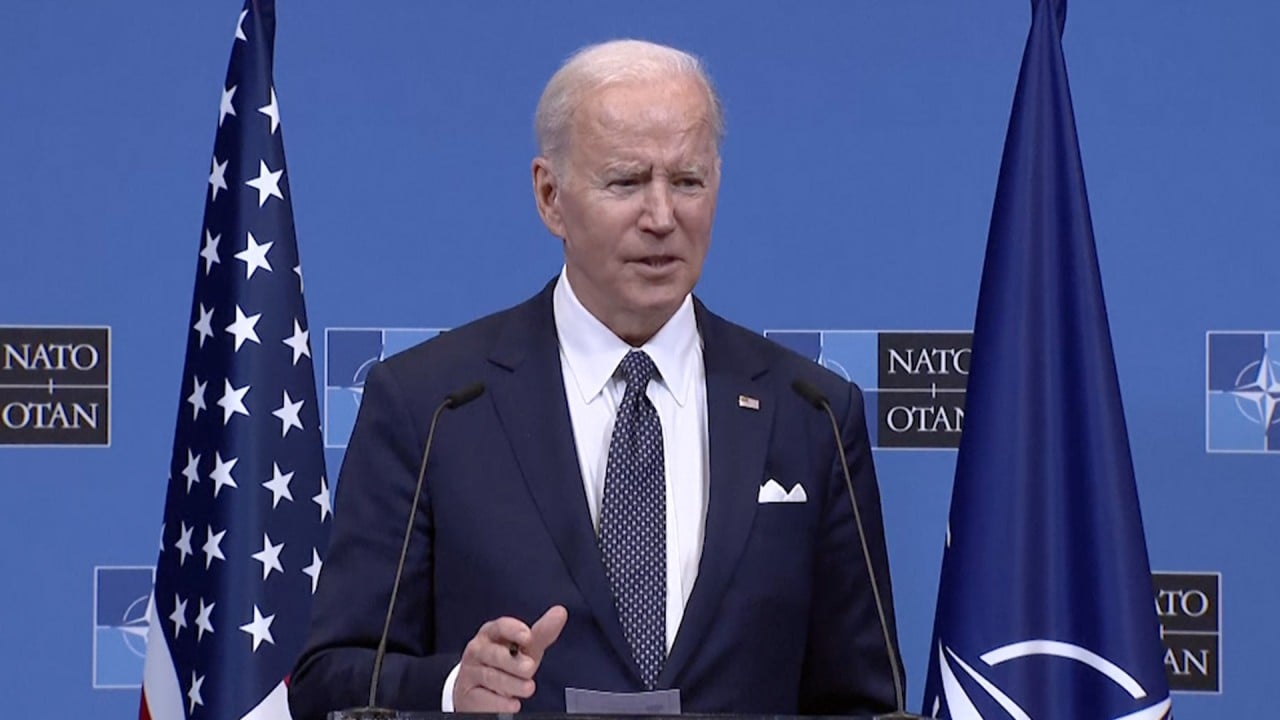

Biden says China’s economic future is ‘more closely tied to the West’ than to Russia

In the next month or so, the United States plans to introduce a new acronym aimed at boosting regional economic cooperation: the IPEF, or Indo-Pacific Economic Framework. Unveiling the idea last year as part of his “Build Back Better World” initiative, US President Joe Biden flagged the framework as ushering in a new era of American leadership across Asia.

It is a response to demands for more US economic involvement in the region beyond the perceived security and defence priorities around Taiwan and the South China Sea. It is also an attempt to rebuild constructively after Donald Trump’s demolition of most multilateral engagement.

What it will add to the existing blizzard of acronyms – Apec, Asean, RCEP, CPTPP – is, as yet, unclear. Also unclear is whether it will be economic rather than a political and security-focused complement to the Quad, whether it will embrace India and whether it will contain any incentives for Asian economies to join. What is resoundingly clear is its role in excluding and containing China.

The Biden team says the IPEF will be built on four pillars: fair and resilient trade; resilient supply chains; building infrastructure and cooperation on clean energy and decarbonisation; and cooperation on tax and anti-corruption efforts. It will be overseen by the US Trade Representative’s office and the Department of Commerce. The aim is to complete the agreement by November next year at the US-chaired Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (Apec) leaders’ meeting.

But even before the IPEF is conceived, hard questions have been raised about its viability. First, there is concern over the ability of Biden’s team to deliver any international trade deal unless it explicitly generates jobs at home and export opportunities for US manufacturers.

Democrats are at times sceptical of the benefits of trade and globalisation, and trade is as toxic an issue in the US as it has ever been. Many around Biden will argue that any trade-related initiative raised ahead of November’s midterm elections will only raise the danger of an electoral defeat.

Even before the details of the framework have been delivered in print, the Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) – a Washington-based think tank – has released a wide-ranging assessment. Based on interviews with governments across the Asia-Pacific, the report says most would welcome more meaningful economic engagement across the Pacific, but they raise several concerns.

First, there are the incentives. As the CSIS report notes, the US proposal includes many asks but few offers: “To practically all regional governments interviewed, prospective US offers under the IPEF are not commensurate with these expected US requests.” Almost all want better access to the US market, but Biden’s Democrats are unlikely to offer it.

Second, there is little evidence of any distinct value in the IPEF that does not already sit in an existing trade agreement, whether bilateral, plurilateral or even in the Trump-traumatised World Trade Organization. Many governments across the region would see value in a specific focus on digital issues, but slow progress in other trade forums makes it difficult to see what digital progress the IPEF could provide.

Third is the question of membership. Some argue the IPEF should be tightly bound to trusted US allies in the region, such as Australia, New Zealand, Japan, South Korea and perhaps Singapore.

The downside would be that many might see this as confirmation the US is primarily concerned with military-security issues in the region rather than economic cooperation. At the heart of this would be whether Taiwan would be included.

Most would like a wider membership. This would be good for the optics and the fact it would embrace a larger share of regional trade and investment, as well as because, for example, the 10 members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) prefer to move as a bloc.

Fourth is the matter of China. Many regional governments question the value of any economic deal that excludes the region’s largest economy and, for many, their main trading and investment partner. This is likely to be problematic.

Even staunch US allies such as Australia export 13 times more to China than to the US, while the Southeast Asian economies are tightly linked to China-based supply chains. In 2021, China-Asean trade amounted to US$878 billion, more than double Asean’s US$384 billion trade with the US. As the CSIS report notes, “The perception of an anti-China bent has a chilling effect on enthusiasm.”

Finally, there is durability. Memories of Trump’s cavalier abandonment of multilateral commitments raise questions about US commitment to any IPEF deal. Even if Biden’s pledges are sincere, the likelihood of losing control of Congress in November and the residual appeal of Trump to the Republican Party generate reasonable concerns about the durability of US leadership beyond 2022.

As the CSIS report concludes: “This can only happen if partners believe there is something in it for them, and that the US is committed to long-term engagement.” It calls on Biden to show more ambition to make a deal relevant and meaningful, and more inclusivity to deliver necessary scale.

Otherwise, there are plenty of other trade agreements across the region, including Apec, the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership which Trump abandoned, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership and the much-maligned WTO.

From a Hong Kong vantage point, there can be no realistic or useful new trade agreement that ducks the obligation to include the world’s two largest economies. There is far more to be gained by building on or broadening the architecture of agreements that already exist. But who cares what Hong Kong thinks? We are unlikely to be invited to the party anyway.

David Dodwell researches and writes about global, regional and Hong Kong challenges from a Hong Kong point of view