01:45

China says ‘no limits’ in cooperation with Russia

The Manicheans among us, who like to divide the world into “good” and evil”, have since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine doubled down on the idea that Russia and China are partners in an evil “axis of autocracy”, which must at all costs be brought to heel by an alliance of democracies.

The narrative has been reinforced by February’s joint statement by Russian President Vladimir Putin and Chinese President Xi Jinping that the relationship between their countries has “no limits” and that there are “no forbidden areas of cooperation”.

Beijing’s refusal to condemn Russia’s invasion – China was one of 35 nations that abstained from the United Nations vote – and its willingness to keep its market open to Russian oil, gas and coal, have prompted many to buy into the narrative, even though it is largely mistaken.

As Kadri Liik at the European Council on Foreign Relations said in a 2021 policy brief, Russia and China are not “two parts of a single problem”.

The reality is that despite a strong personal relationship between Putin and Xi – the two have met about 40 times since 2012 – China and Russia harbour deep mutual distrust that goes back to “unequal treaties” in the mid-19th century, and have little in common and divergent futures.

Their “marriage of inconvenience” hinges on a common shared suspicion of a number of Western powers and geographic factors, including a 4,300km (2,800-mile) border, one of the longest in the world.

Russia’s jealousy of China’s growing influence in Central Asia and the Russian Far East requires constant delicate management. In 2000, China’s imports from Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan were less than a quarter of Russia’s imports. By 2020, they were more than double Russia’s imports.

Whatever the apparent cosiness of present Russia-China ties, the relationship over the past 180 years has more often been in the deep freeze.

Russia was one of several Western powers that imposed “unequal treaties” on China. Under the 1858 Treaty of Aigun, China had to cede 600,000 sq km (232,000 square miles) of land to Russia, and under the 1860 Treaty of Peking, China forfeited a large chunk of its northeastern territories to Moscow.

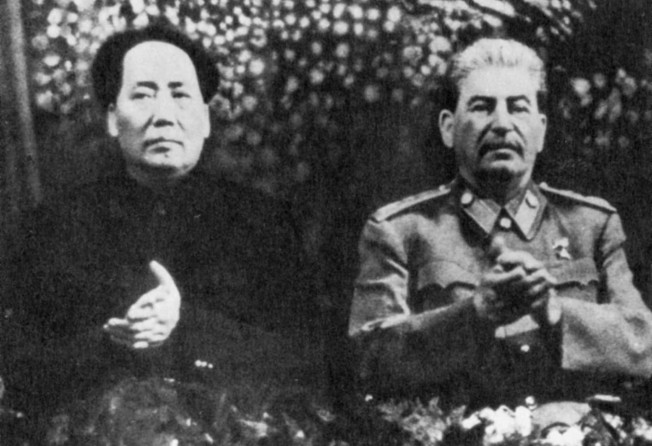

Many in China have grim memories of Mao Zedong’s 1949 visit to Moscow, just two months after coming to power. It took two months of humiliating hard bargaining with Stalin to get the friendship pact he desperately needed.

That Russian view of China as a poor and dependent younger brother created deepening stresses and resentments as China became wealthier.

China’s rise has generated one of the most serious sources of stress between the two countries. In 1990, during the break-up of the Soviet Union, Russia’s gross domestic product was virtually on a par with China’s – around U$1 trillion (based on constant 2015 US dollar).

By the end of last year, China’s GDP had grown 15-fold, while Russia was only 28 per cent up. Even more significant, China’s military spending is US$239 billion, almost four times Russia’s US$65.9 billion, while research and development stands at US$465.2 billion (on a 2018 purchasing power parity basis), over 10 times Russia’s US$41.5 billion.

As China has grown, its reliance on “big brother” has shrivelled. Of Russia’s total US$550 billion trade in 2021, 18 per cent was with China. But Russia accounted for only 2 per cent of China’s US$4.2 trillion trade. Most of Russia’s exports are linked to fossil fuels, demand for which will decline as Beijing moves towards a carbon-neutral economy by 2060.

This has led to a marked difference in attitudes to international relations. Russia is diplomatically at odds with the West, largely disconnected from the global economy, and with little to lose from conflict. China, however, sits at the heart of international trade, connected by complex supply chains across the global economy, with lots to lose in the event of conflict.

Russia’s willingness to act aggressively in what it perceives to be its national interests – in Chechnya in 1999, Georgia in 2008, Crimea and more largely Ukraine since 2014, and in the Syrian civil war from 2015 – contrasts with China’s more reluctant posture on military action.

If there are only two lessons for China to learn as it watches Russia pay the price for its Ukraine invasion, they are that a military invasion of Taiwan would be hugely expensive and challenging to win, and that the harm to the economy and China’s place in global trade would be catastrophically high.

Despite their pragmatic relationship, Russia and China have been reluctant either to support, or to criticise, each other’s controversial international arguments. Just as China abstained from the vote condemning Russia over Ukraine, and stayed neutral on the 2014 annexation of Crimea, so Russia has not criticised China on Tibet, Xinjiang and Beijing’s territorial claims in the South China Sea.

While China’s reluctance to provide formal support has often irritated Russia, Liik at the European Council on Foreign Relations notes that Moscow’s forbearance arises because China, being a growing power, has to be tolerated as “a geopolitical fact of life, like it or not” and because “China does not commit the sin of telling others how to live”. So the idea of a “no limits” relationship between Russia and China should be taken with a pinch of salt.

In reality, China’s interests are set to diverge further from Russia’s, and converge more closely with the interests of many countries that today treat China with deep suspicion. That will undoubtedly create its own set of challenges, but they will have little to do with Russia or any “axis of autocracy”.

David Dodwell researches and writes about global, regional and Hong Kong challenges from a Hong Kong point of view