Philippe Parreno’s Synchronicity rethinks art, as Shanghai exhibition space becomes immersive centrepiece

The French artist has used the walls of the Rockbund Art Museum as a canvas, turning the space into a moving, sensory experience focused on humans and nature

French artist Philippe Parreno has spent decades challenging the notion of artworks being shown in exhibitions as mere objects. For the 53-year-old master of multiple disciplines, a show should be an artwork in itself – a living, breathing, moving, changing work. The exhibition becomes, in essence, a dialogue with the space, putting some artistic meat on a gallery’s architectural bones.

Shanghai’s Rockbund Art Museum (RAM) – with four floors of wide open white space – offers Parreno the perfect canvas to work on.

“Synchronicity”, the artist’s first solo outing in China, is made up of multiple artworks, each telling a layered story that can stand alone or be read as a broader narrative about time and the interplay of humans and nature.

On the second floor is a new version of Parreno’s film Anywhere Out of the World (2000), in which the 2D animated manga character Annlee – an alien with a lipless mouth and tiny nose – is revisited in stereoscopic 3D. A newly added voice narrates a monologue about Annlee’s nature as an invented character.

Parreno offers visitors the opportunity to get inside the art and to become a part of it by engaging with it.

This update in Annlee’s story continues her “life”, as much as a manga character can be considered to have a life. She was initially destined for the cutting room floor before being bought by Parreno in the late 1990s, and has since made several appearances in films by Parreno and other artists. She was then ceremoniously killed off in 2002.

The film is notable for Annlee’s level of self-awareness as a central character, giving her a more human-likeelement than might otherwise be expected of a cartoon character. It raises questions about what is real and unreal and the nature of life and death for someone so clearly not alive.

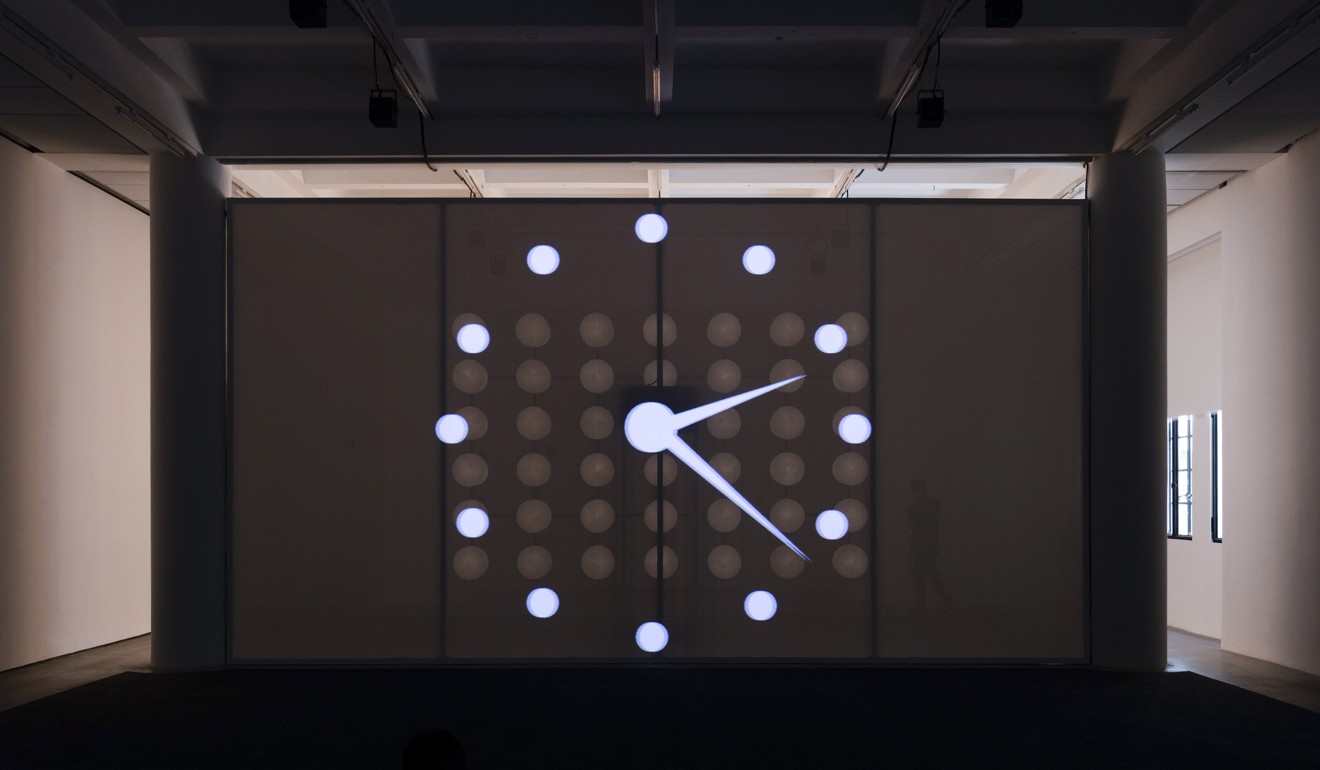

As her spiel ends, spotlights from behind the screen flash and an analogue clock appears. White blinds over the windows are raised and lowered automatically, like blinking eyes adjusting to the daylight pouring into the room.

On the third floor, a tune plays that resonates throughout the exhibition space. The time is also displayed in large numbers styled to look like a digital clock on the central wall.

But the installation, an update to Parreno’s Fade to Black series of 2003, is actually fluorescent numbers screen-printed on posters, then hung and removed by pairs of volunteers.

The volunteers are referred to as “dalangs” – the name for traditional Indonesian puppeteers – who also raise and lower window blinds in a choreographed routine of lightening and then darkening the room for each new, updated time to be revealed. It’s a trick. What looks digital, is actually incredibly lo-tech.

It’s on this floor that the “Synchronicity” title becomes most apparent, as people simultaneously work to both create the time by hanging the numbered posters and reveal it by lowering the blinds.

On the next floor up is a cavernous space, with natural light flooding in from a skylight – it showed a rare expanse of blue sky for a Shanghai summer day when we visited.

A dozen cubed speakers dangle from the mezzanine space, surrounding visitors with the sound of rain hitting the earth and flowing, as though along a swollen creek. Then thunder and lightning is simulated by the flashing of florescent lights, before a sudden silence.

The digitally enhanced sound reverberates in such a wide, open space. The effect is both oddly calming – as the sounds of nature tend to be – as well as disconcerting – as you stand there surrounded by hospital-grade whitewashed walls and concrete.

In making the exhibition the artwork, Parreno offers visitors the opportunity to get inside the art and to become a part of it by engaging with it. It’s unclear, though, how well this invitation to interact is being translated to audiences in Shanghai.

There is little to no explanation of what is happening as they make their way through the different floors. The chance to take part in the process of making the artwork largely seems to bypass visitors who aren’t aware of the artist’s intention.

Curated by museum director Larys Frogier, the exhibition runs until September 17.