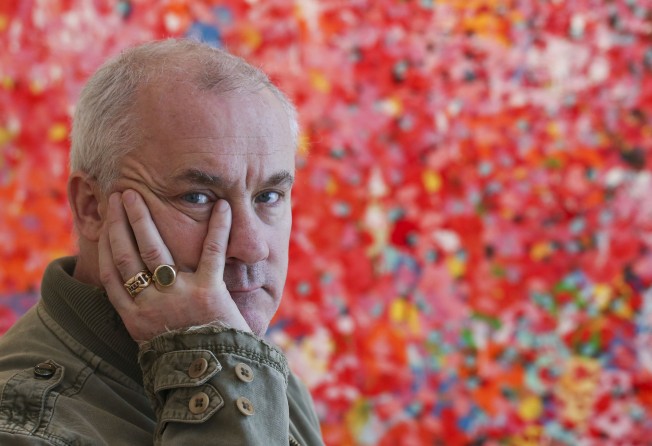

Damien Hirst, focused and funny, is back at Gagosian in Hong Kong with his pickled sharks

‘I prefer them now to when I made them’, says British artist about show of early works featuring preserved animals, his first in Hong Kong since 2011, and quips he’s ‘the patron saint of tourism’ in Venice, site of his latest provocative show

In January 2011, when Hong Kong was still deciding whether it could reinvent itself as an arts hub, the New York dealer Larry Gagosian opened a gallery in the city. It was his 11th worldwide but his first in Asia.

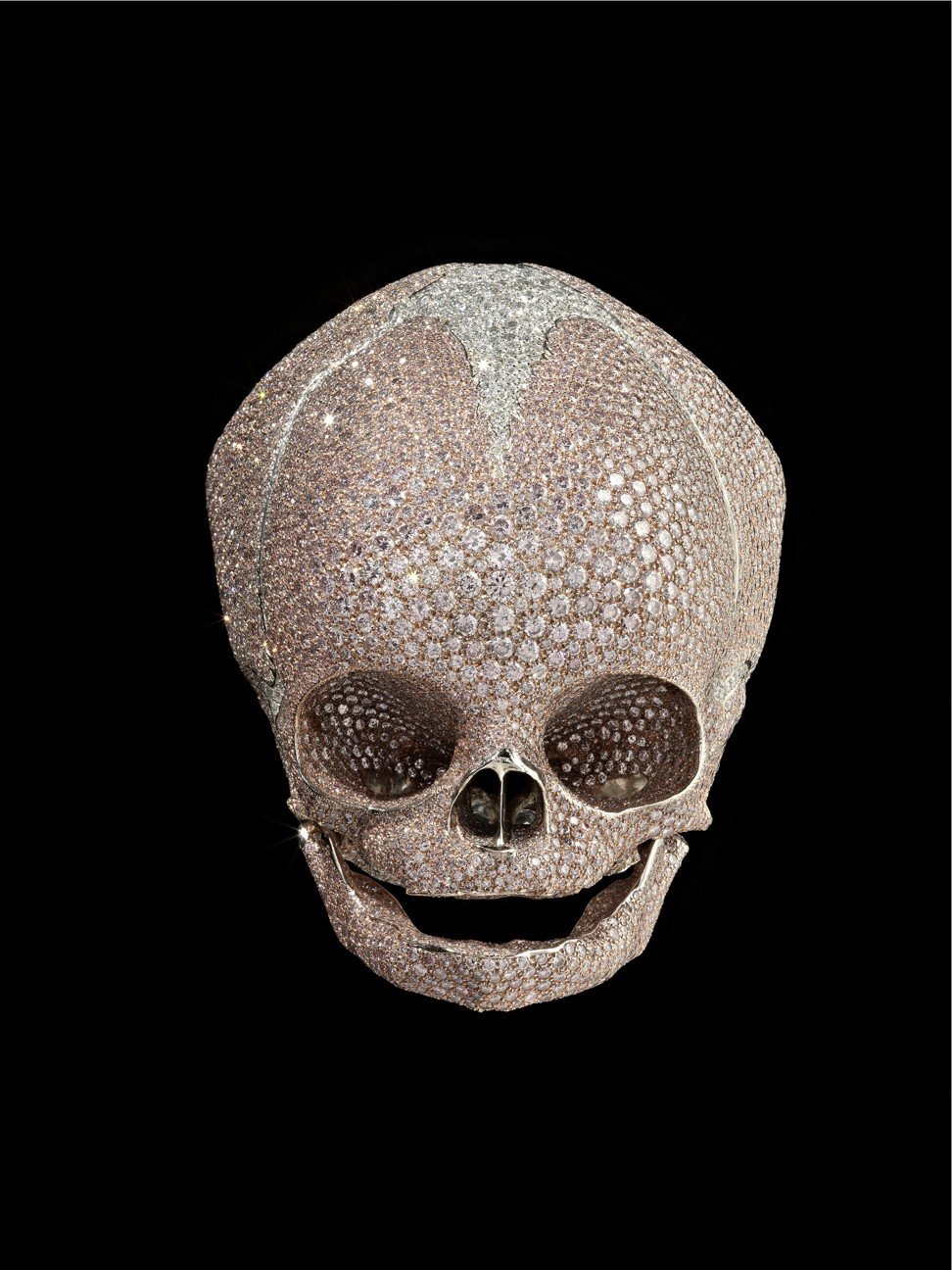

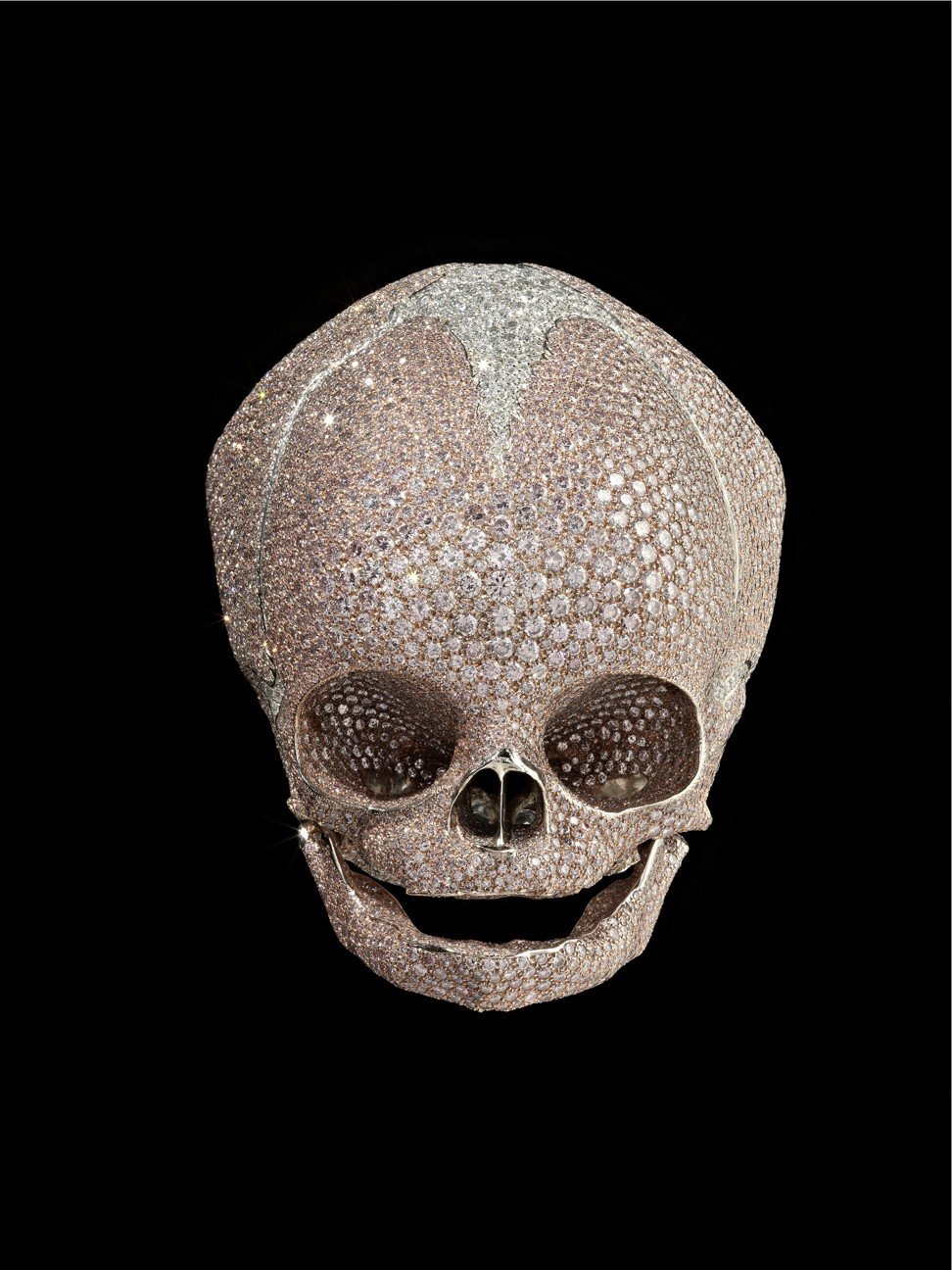

Such an occasion required a megaphone artistic presence. At the time, there was really only one contender: Damien Hirst, one of the world’s wealthiest artists. He came, he obligingly brought the cast of a baby’s skull studded with 8,000 diamonds and global debate ensued (bling vs morality). Job done.

Six years later, he’s back. There have been other Hirst shows in the city: Gagosian galleries worldwide collectively showed 25 years’ worth of his spot paintings in 2012, while White Cube gallery had an exhibition of his entomology cabinets and scalpel-blade paintings in 2013. But the new show, “Visual Candy and Natural History”, at Gagosian in Central is mostly confined to works from 1993 and 1994, and, curiously, this exhibition feels like the introduction people might have expected in 2011.

For one thing, there are pickled sharks on show. Also pickled calves, pickled sheep, a pickled dove and a pickled oven-ready turkey (which, as the staff kindly point out, isn’t a Thanksgiving turkey). There’s a cow’s head laying in a puddle of fly-blown blood. There’s also a series of wildly exuberant paintings collectively called Visual Candy. And there are the memorable titles: Zipedeedoodar and Two Similar Swimming Forms in Infinite Flight (Broken) and Myth Explored, Explained, Exploded.

Hirst has always been clever with words, and the evidence of that plus the themes that still obsess him – liquids, contained spaces, animals, sequences – are striking. A few of the exhibits are showing their age: condensation pearls the glass, the tanks in which the calves Cain and Abel are forever suspended on tiptoe have required a coat of new paint.

The early 1990s is when he laid out his stall: most of these works were created before his Turner Prize win in 1995. “I prefer them now to when I made them,” he says after a short scrutiny. Possibly that’s because he’s more preferable to himself now than then.

What he sees in the works is a young artist who staked a claim to an insult (at the time, a critic had sneered about the spot paintings) but who didn’t have the conviction to paint a large enough riposte, which is why they’re relatively small.

The ironic titles – Fun Fun Fun Fun, Dippy Dappy Dabby, Happy Happy Happy – suggest mania. “It’s a sort of psychotic happiness isn’t it?” he says. “Endlessly happy, infinitely happy – maybe a drug-induced happiness.”

As a young artist, he applied himself to the rigours of working with formaldehyde (which he uses to preserve his subjects). From the beginning, science and art have been twin aspects of his professional life (his company is called Science Ltd), pulling him in different directions.

“I’d always think my work was like a group show, like many different artists [were coming together to create],” he says.

The famed drinking didn’t help, either. “If anybody asked [me] a complicated question, I’d always say, ‘There are a lot of people in here, which one are you asking?’” he recalls. But by realising that he didn’t have to tie himself to “this individual artist thing”, it freed him to do everything.

“I do go to my studio sometimes and think ‘Who is this man?’ There’s so much going on, you’d think he’s insane,” he says.

He doesn’t appear insane. The drugs and drinking stopped in 2002. In 2011, he’d arrived for an interview more or less straight from Phuket, beach-baked anddisinclined to be serious; this time, though, he’s funny but focused.

Perhaps it’s his age – he’s 52 – or perhaps it’s the video team filming the encounter, or perhaps it’s a side effect of working on his autobiography with James Fox, who did such a magnificent job crafting Life out of the mayhem that is Keith Richard’s existence.

Why is so much of his work enclosed?

“I feel really uncomfortable with open space. [Artist] Sarah Lucas, who’s a friend of mine, she’d put fragile things on a table and I hate that. I want a big box round it. This space, this tank, this box is owned by Damien Hirst,” he says. “The idea that it’s in the world and I’m not there and people can mess around with it and touch things – I could never relax with that.”

Hirst appears to be fine with the world’s critical opinion, of which there has been much this summer. In May, “Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable” – a project on which he’d spent 10 years and millions of dollars – was unveiled at the Venice Biennale.

The response, rather like his own artistic impulses, were pulled in two directions: ArtNews.com calling it, “devoid of ideas, aesthetically bland and ultimately snooze-inducing”, while The Guardian labelled it his “titanic return”.

“Mixed reviews – brilliant,” Hirst says, with what seems to be genuine enthusiasm. “What I love is when they start arguing among themselves, that’s great.

“If you work it all out in the studio and get behind it and believe in it, it doesn’t matter what other people say.”

The premise of “Unbelievable” is that it’s the wrecked collection of a former slave called Cif Amotan II – an anagram for ‘I am fiction’ – discovered off East Africa in 2008. With its catalogue of solemn analysis by, for instance, English historian Simon Schama, it’s such a perfect exhibition for our post-truth world that the real wonder is how Hirst managed to tap into the 2017 zeitgeist a decade ago.

“It is lucky but it’s instinctive as well,” he says. “After I was making pieces with chickens or cows like Cain and Abel, salmonella and BSE (bovine spongiform encephalopathy) was in the press.”

The exhibition in Venice closes on December 3 when, Hirst says, its constituent parts will be dispersed and it will enter the realm of myth. “The feeling I have is that it’s safer then.”

Safer? “It’s conceptual art you can look at now but it’s much better, with conceptual art, to talk about something you can’t see.”

In January, Netflix will show a documentary about the exhibition and its creation. (Myth explored, explained, exploded, perhaps.)

One of the rescued “treasures” is The Collector, an apparently barnacled, coral-encrusted statue of what looks suspiciously like Hirst himself. What’s that about? “I was hoping you could tell me!” he exclaims.

Well, maybe it’s a man who fell to the bottom of the sea, weighed down by the growth of possessions over the years, who’s finally been brought to the surface. Can it be a coincidence that the legendary shipwreck of the “Unbelievable”, scattered across the sea floor, as Hirst describes it, was “found” in the same year that he famously sold 223 artworks for about US$200 million at Sotheby’s?

Or maybe he’s simply thumbing his nose at the art world. “I always do that,” Hirst says. “If the market’s getting me down, I just distance myself from it. But if you do that, you just create another market, so there’s no escape.”

And speaking of distance – in 2012, the year after he came to Hong Kong for the opening of the Gagosian, Hirst left the gallery after 17 years. Now here he is, all smiles, back with Gagosian again. “There is a commercial side to art which you need to get rid of so you can focus more,” he says.

“I left Larry [Gagosian]. Then I had this [Venice Biennale] project that’s so big, Larry’s the only person who can sell it. I’d kept my friendship with him during that time and he came round and looked at it and liked it.”

So had he discussed the showcase with Gagosian at the beginning of the 10-year project? Hirst nods. “I think so, yeah. And with Jay [Jopling, founder of White Cube]. But they didn’t really get it. It’s like ‘what have you got for me now, not in 10 years?’”

There’s no lolling about after his decade’s toil. He’s rushing back to get on with the many other projects waiting in the controlled, enclosed space that is his studio and which he describes as his “favourite place along with bed”.

Having his finger so firmly on the political pulse, of course, he’s thinking of getting an Irish passport “because of this Brexit bullshit”.

It means you don’t get spat at in other countries in Europe,” he says. Did anyone spit on him in Venice? Hirst grins. “No, I’m the patron saint of tourism there.”

“Damien Hirst: Visual Candy and Natural History”, Gagosian, 7/F Pedder Building, 12 Pedder Street, Central, until January 13, 2018