When Britain sent Malayan Chinese into exile and sometimes death: taboo-breaking exhibition brings a dark episode to life

It’s a cold war episode many would prefer stay buried: Britain’s ultimatum during the Malayan Emergency to leftist Chinese of jail or deportation. The discovery of a family secret led a Singaporean photojournalist to trace surviving deportees and tell their stories

Revelations about a grandfather who died before she was born stirred photojournalist Sim Chi Yin to delve into her family history and a little-known chapter of the Malayan Emergency: the large-scale deportation of ethnic Chinese by the British just after the second world war.

The Singaporean photojournalist has lived in Beijing since 2007, where she was first the China correspondent of The Straits Times and, since 2011, a freelancer working on socio-political stories.

In between assignments about the treatment of migrant workers, pollution in China, and North Korea (the 2017 Novel Peace Prize commissioned “Fallout”, her exhibition about nuclear weapons currently on show in Oslo), Sim has interviewed, photographed and filmed dozens of surviving deportees now living in southern China, Hong Kong, Malaysia and Thailand.

They were all accused of being leftist guerillas or were their supporters during the bloody communist insurgency from 1948-60.

Sim’s grandfather was Shen Huan Sheng (the mandarin pinyin of his Chinese name), a school principal and editor of the Chinese language Ipoh Daily. His paper published a lot of anti-British editorial and he was arrested at his family’s provision shop in Selama, near the northern Malaysian city of Taiping, and taken to a detention camp in Taiping, in Perak State.

Shen and around 31,000 other Malayans were given a choice: stay in jail or be deported to their ancestral “homes” in China via Hong Kong so that they would not be able to stir up trouble in Malaya. He opted for freedom and a new life in Meixian, in Guangdong.

“He promised my grandmother and their children he would settle down and send for them. Two years later, a letter came from China saying he had joined the local Chinese Communist Party, been arrested by the Kuomintang and executed,” Sim says.

Eventually, an aunt produced a particularly poignant photograph of Shen – the newspaperman posing with a twin lens camera – a photograph of him in jail and a letter from the Sims’ Meixian relatives.

My grandmother died when I was 15. When she was alive, she banned anyone from talking about grandfather, or about politics, or China

The photos are among the archival images that form part of “One Day We’ll Understand”, Sim’s first attempt to present her seven-year research to the public and part of a multimedia group exhibition at Singapore’s Esplanade. Art, rather than a documentary, allows her to tell a complex and layered history in a non-linear and multidisciplinary fashion.

Detailed captions give you the background narrative. A watercolour of St John’s Island, just off Singapore, dated June 1949, was the work of a detainee Cen Yuan Zhi. The Ipoh native had painted every detainee who came into the St John's Island camp while he was there.

There is a photograph of a crudely made prosthetic leg that the Malayan communists used during the guerilla war. That was found in the jungle bordering southern Thailand – an area covered in landmines – and now sits in a museum in Peace Village converted from a former communist camp.

An image of David Alexander Adamson’s grave in Perak is a reminder of the other side of a protracted war that killed thousands, including British plantation owners such as 25-year-old Adamson, who was murdered in his home by the guerillas.

“My story is more focused on the leftists because of my family connection and because theirs are the unwritten tales. But I also interviewed a man in the British home guard and a man whose brother was killed by the communists,” she says.

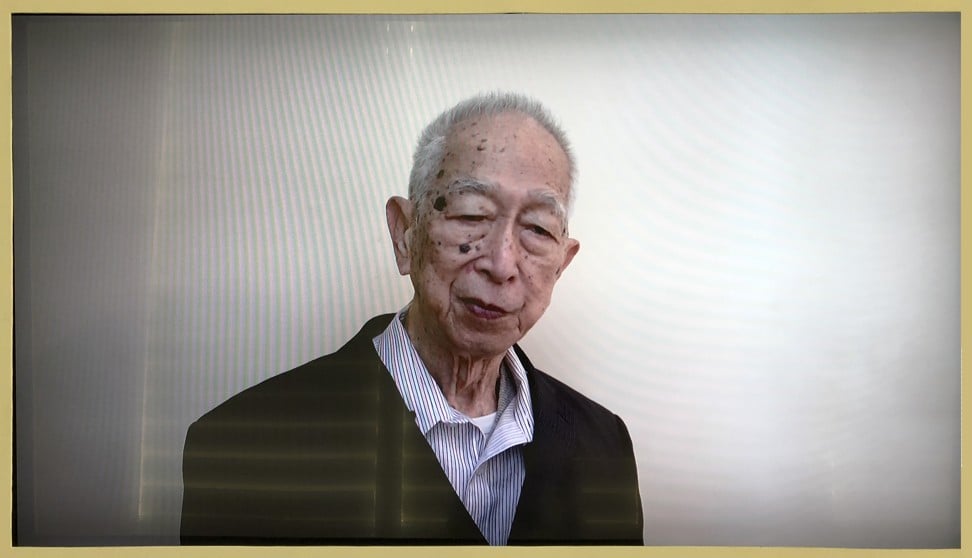

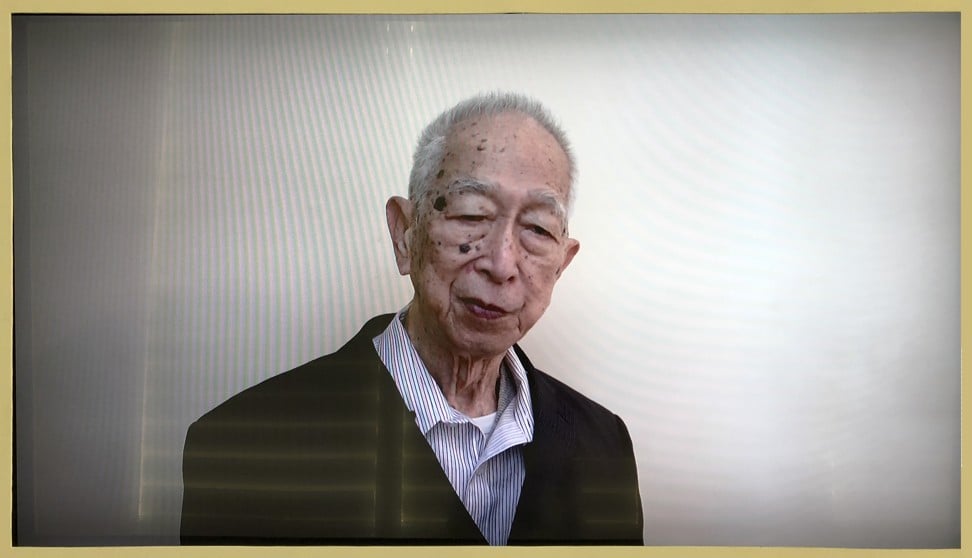

The most affecting of the exhibits are two videos showing people in their nineties recalling, through songs, the moment their ships set sail from Malaya. On one screen, 96-year-old Cen – the painter – sang parts of “Goodbye Malaya” that he could remember. He now lives in Hong Kong.

On the other screen, 92-year-old Zeng Zheng in Foshan, Guangdong, plays “Protect Malaya” on the piano – an anti-Japanese anthem in Chinese during the Japanese occupation from 1941-45.

I really want to get at some of the layers of trauma and memories left over from the early cold war

“She learned the piano in her eighties to ward off dementia. Of all the interviews I did, this piano tune is what really punched me in the gut,” Sim says.

Zeng was an exception here. She wasn’t deported. She was driven by her own conviction to join the Communist revolution in southern China.

Many people who were deported involuntarily were not at all ideological, Sim says. “The less educated ones, such as rubber tappers, simply became mobilised and joined the guerilla movement out of a feeling that they had been let down by the Brits during the second world war. The anti-colonial sentiment bound them together, not ideology,” she says.

Such relatively recent history is rarely discussed, even though many other families would have been touched by events similar to what her family went through, Sim says.

Most Singaporeans were taught growing up that the communists were the enemies. Her own family had reservations about the exhibition and public activities around it because they still see communism as a dirty, dangerous word. But Sim is determined to carry on her research and publish a book on the topic.

“The world is so different now. Singaporeans don’t even think of China as communist any more. I really want to get at some of the layers of trauma and memories left over from the early cold war. It is a memory common to so many in our part of the world,” she says.

“One Day We’ll Understand” is part of the “Relics” exhibition, which also features works by Phan Thao Nguyen and Sarker Protick that explore the region’s colonial legacy.

Relics, Jendela (Visual Arts Space), 1 Esplanade Drive, Singapore. Until April 1