Are dead bodies of Chinese prisoners on show in Sydney? It wouldn’t be the first time an exhibition courted controversy

The Real Bodies exhibition in Sydney has come under fire, with protesters asking whether the cadavers displayed are those of prisoners executed in China. We recall five other art shows that raised hackles

Are bodies of Chinese prisoners really on show at an exhibition in Sydney? That’s what protesters claim is the case with Real Bodies, a show in the Australian city’s Byron Kennedy Hall that features bodies and anatomical specimens that “have been respectfully preserved to explore the complex inner workings of the human form in a refreshing and thought-provoking style”, according to the exhibition’s website.

The protesters – a group of academics and human rights campaigners – are urging the boycott and closure of the exhibition, which is billed as featuring the largest collection of bodies and human specimens ever put on show in Australia.

According to The Guardian, Vaughan Macefield, a professor of physiology at the University of Western Sydney, said it was “appalling that in 2018 such specimens from China were being displayed to members of the public who were unaware of their origin”.

Tom Zaller, chief executive of Imagine Exhibitions – the company organising the show – told NewsCorp ( a media sponsor of the exhibition) that the bodies came from China, a detail that raised flags with human rights activists.

Susie Hughes, executive director of the International Coalition to End Transplant Abuse in China (ETAC), asked whether the bodies had been obtained ethically.

In 2016, China came under international fire when reports surfaced that the government was illegally harvesting organs from prisoners despite saying it had ended the practice two years earlier. At the time it was estimated that between 60,000 and 100,000 such organs were transplanted annually.

This is hardly the first time art has courted controversy. Here are five other exhibitions that caused a stir:

Art and China after 1989: Theatre of the World

In September last year, New York’s Guggenheim museum bowed to pressure and removed three contentious pieces from an exhibition, “Art and China after 1989: Theatre of the World”, after protests because they feature live animals.

The museum received thousands of calls, emails and letters from animal rights activists protesting about what they saw as the abuse of animals. Huang Yongping’s Theatre of the World, for example, showed live insects and reptiles trapped in a survival-of-the-fittest habitat.

“People who find entertainment in watching animals try to fight each other are sick individuals whose twisted whims the Guggenheim should refuse to cater to,” wrote Ingrid Newkirk, the president of animal rights group PETA, to museum director Richard Armstrong at the time.

Their removal raised accusations of censorship.

Ai Weiwei

Chinese artist and activist Ai Weiwei, who is critical of the Chinese government’s stance on democracy and human rights, is never far from controversy. In 2017, he launched a contentious public art project focusing on immigration called Good Fences Make Good Neighbours.

The project comprised 300 installations around New York based on the concept of fences and borders to show, according to Ai, the “narrow-minded” attempts used to “create some kind of hatred between people”.

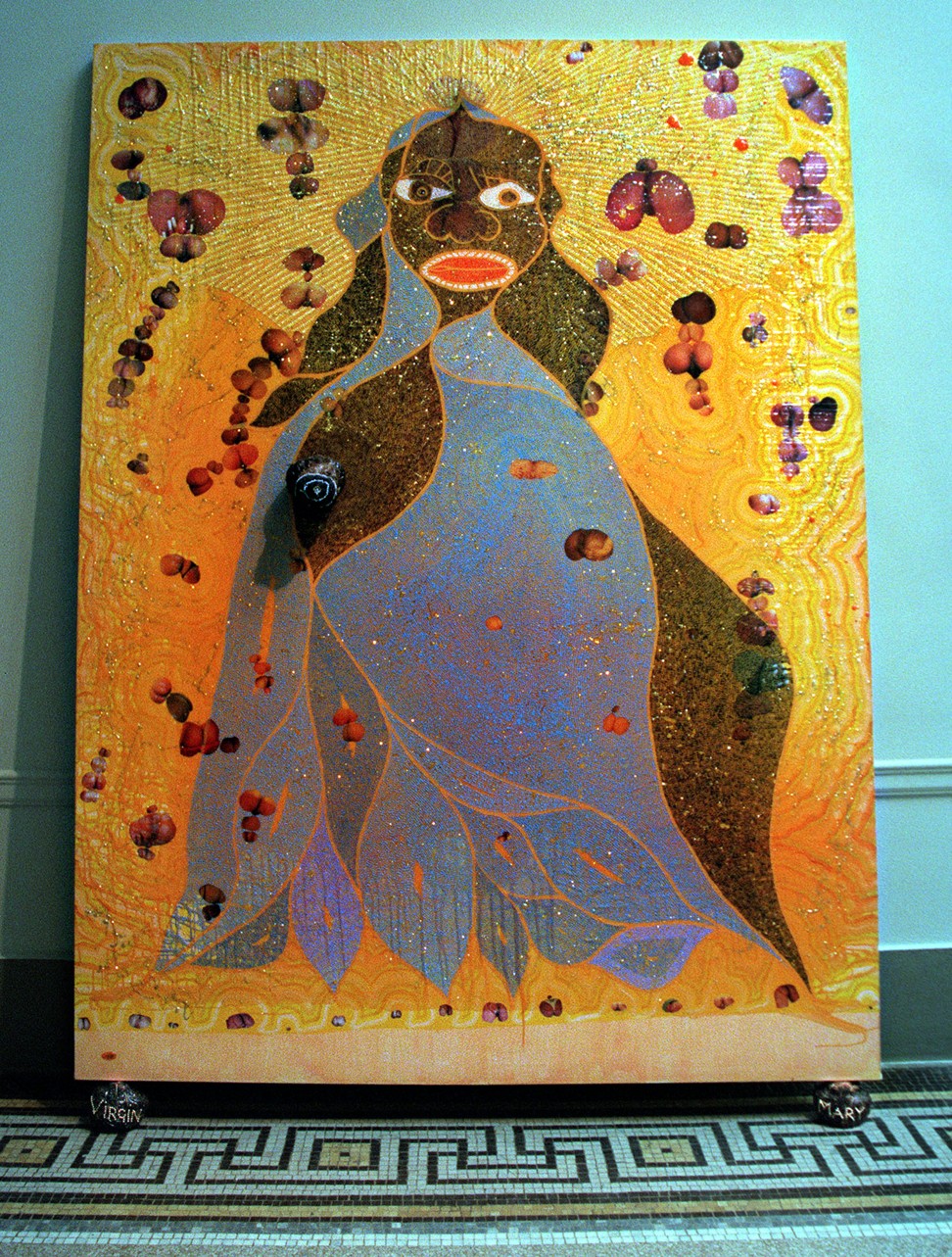

The Holy Virgin Mary

Mix art with religion and it’s bound to rub some people up the wrong way. Turner Prize-winning artist Chris Ofili’s mixed media painting of a black Virgin Mary was always going to do that.

Adding fuel to the fire, British-born Ofili added images to the work of female genitalia cut from pornographic magazines, while a bare breast was made from elephant dung.

When it went on display in New York in 1999, then mayor Rudy Giuliani called it disgusting and tried to sue the Brooklyn Museum to have it removed.

Banksy

Banksy has pulled off so many pranks and caused so much controversy that it’s difficult to pinpoint one. In 2003, using a hammer and nail, the anonymous UK-based graffiti artist, political activist and film director hung his own work on one of the Tate Modern’s walls. It was accompanied by the caption: “This new acquisition is a beautiful example of the neo post-idiotic style. Little is known about Banksy whose work is inspired by cannabis resin and daytime television.”

In 2007, Banksy struck again when he graffitied a wall in the West Bank town of Bethlehem in Israel. His art was defaced by locals who found it offensive.

The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living

We couldn’t leave out Damien Hirst. Never a stranger to controversy, the British artist caused quite a stir with his 1991 instalment of a 14-foot (4.3-metre) tiger shark suspended and preserved in formaldehyde.

The piece was commissioned by Charles Saatchi, the Iraqi-British businessman and co-founder of Saatchi & Saatchi, who sold it for about US$12 million. The exhibit enraged animal rights groups who considered the work inhumane, while art critics thought it just wasn’t art.