Book review: the left’s part in putting black America behind bars

Harvard historian Elizabeth Hinton's book From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime explains how liberal politicians, not just conservative Republicans, are responsible for the mass incarceration of black Americans today

by Elizabeth Hinton

Harvard University Press

4/5 stars

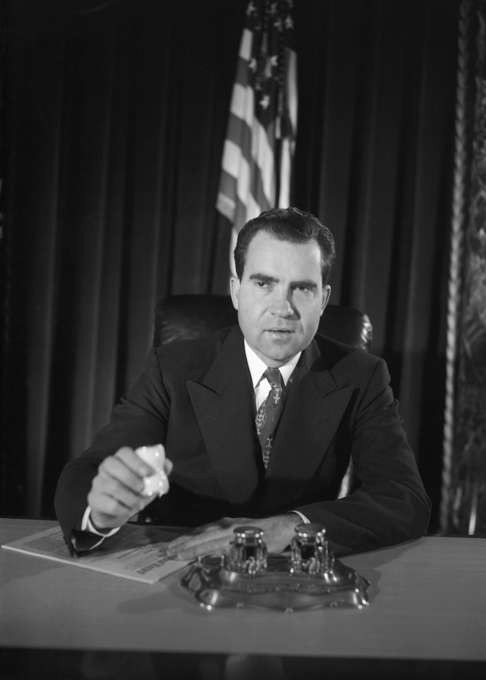

What if the mass incarceration and policing of African Americans in the United States was conceived not by reactionary Republicans but progressive Democrats? What if, in order to understand why police in the United States kill people daily and why there are about a million black faces behind bars in that country, you need to consider not just the usual bogeymen of Ronald Reagan and Richard Nixon, but also the liberal lions John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson?

These are questions provoked by Elizabeth’s Hinton’s magisterial new history, From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime: The Making of Mass Incarceration in America. Hinton argues that modern America’s imprisonment state was built over decades “by a consensus of liberals and conservatives who privileged punitive responses to urban problems as a reaction to the civil rights movement”.

Harper’s Magazine recently published an interview from 1994 with disgraced Nixon aide John Ehrlichman in which he said drug prohibition came about because the Nixon White House “had two enemies: the antiwar left and black people”. As they couldn’t outlaw either, they got “the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin” and criminalised both to destroy them.

While Hinton deals with Nixon and his “long-range master plan” for prison in the latter half of her book, she also explains that “even if all the citizens serving time for drug convictions were released, the United States would still be home to the largest penal system in the world”. She delivers a more wide-ranging indictment of liberalism instead.

Hinton sketches how free black people have been systematically shut out of American opportunity since slavery. By the 1890 census, blacks formed 12 per cent of American society and 30 per cent of its prisoners – and that over-representation only increased by the mid-20th century. Meanwhile, by the 1960s, “unemployment rates of African Americans were more than double their white counterparts” – similar to how black people today are twice as likely to be unemployed as their white counterparts.

Liberalism failed to target the economic inequality wrought by decades of systemic racism. Instead, it blamed the personal moral failings of contemporary young people. With its “total attack” on youth delinquency, the Kennedy administration began pinning the scourges of poverty and racism on troubled kids. Kennedy’s social policies pathologised teenagers in the “inner city” and called for the creation of punitive juvenile detention centres – but none of that made any of those increasingly policed kids, or the communities they lived in, any physically or economically safer.

It was really his successor, Lyndon Johnson, who cleared the path for mass incarceration. In March 1965, Johnson sent “three bills to Congress that epitomised the federal government’s ambivalent response to the civil rights movement”: the Housing and Urban Development Act, the Voting Rights Act, and the Law Enforcement Assistance Act.

The first two, ostensibly, were meant to help poor black people, by increasing access to housing and to the vote. But the third – not talked about now as much as the other two – put the federal government into the local law enforcement business just as black political power was rising. Federalisation opened the door for private business to sell local governments military gear, on Uncle Sam’s dime, in order to keep that power in check. Johnson’s efforts, Hinton argues, were thus a“manifestation of fear about urban disorder and about the behaviour of young people, particularly African Americans”.

Johnson quickly followed the War on Poverty with the War on Crime, which he called “a war within our own boundaries” that “costs taxpayers far more than the Vietnam conflict”. The wars’ casualties quickly and disproportionately became black people.

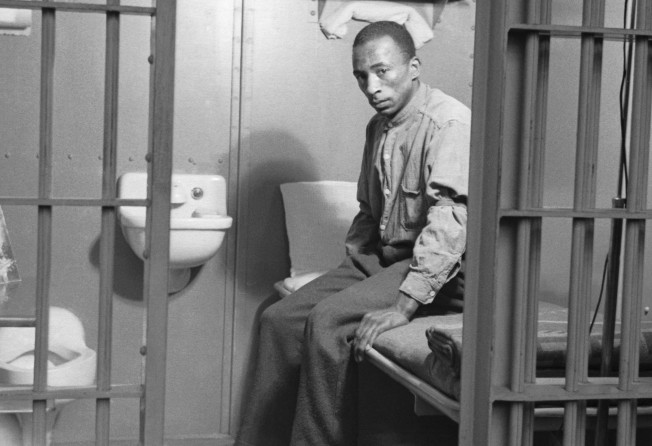

Hinton also charts the rise of programmes like Police Athletic Leagues and gives urgently needed context on the current debate about community policing. There’s a great photo in the middle of the book of young black men playing cards in a teen centre with cops in Washington in 1968. These efforts to improve community relationships with the police also had a sinister side: they were pre-emptive strikes for cops to find “potential criminals” under the cover of providing social services. Eventually, “policing became the main form of social service – when drugs came, folks had no one to call but the police”.

Hinton doesn’t only blame the police, though. She tracks how money is spent on building prison-like security features to public housing in St Louis, charts money spent on job training programmes, and demonstrates how the LEAA budget grows 13-fold. And yet “a federal employment drive to create jobs for black men never materialised” in the manner of the Works Progress Administration, which rescued impoverished white people during the Great Depression. At the same time, in allocating generous funding through the Office of Law Enforcement Assistance, the Johnson administration did underwrite robust hiring in nearly all-white police departments – some of which also began patrolling inner-city school campuses.

Johnson once said: “No right is more elemental to our society than the right to personal security and no right needs more urgent protection.” This was the “all lives matter” argument of its day: a dog whistle to scare white voters into believing black civil rights were a threat to their safety (and a playbook that Oval Office aspirants, not to mention the NRA, have evoked ever since). Some of the goals of the Great Society might have been lofty, but its execution by Johnson and his successors gave the US expanded surveillance and its present prison nightmare instead.

The Guardian