If ever there was a one-book wonder, that wonder was Thomas De Quincey. Few people could name another book after Confessions of an English Opium Eater, and yet his collected works run to 21 solid volumes – mostly essays, including such classics as On Murder, Considered as One of the Fine Arts. But as Frances Wilson writes in this exceptional biography, “Opium was the making of him”, and the Opium Eater persona stuck. It more than answered his dilemma in a teenage diary, agonising over his “character”: should he be “wild – impetuous – splendidly sublime? Dignified – melancholy – gloomily sublime? Or shrouded in mystery – supernatural – like the ‘ancient mariner’ – awfully sublime?”

De Quincey was hardly the first person to take opium – everybody took it in his day, and, more than that, they took it for granted – nor was he the first person to take it recreationally, as we might say today (or as he puts it, “for luxurious sensations”). But he was the first person to frame it so exotically, with an orientalism that is by turns playful – the title of English Opium Eater is a joke, an oxymoron that we barely hear now, because “opium eaters” were implicitly Turks – and beautifully horrifying: “I ran into pagodas, and was fixed, for centuries, at the summit or in secret rooms: I was the idol; I was the priest: I was worshipped; I was sacrificed … I was buried for a thousand years … ”

Confessions of an English Opium Eater.

De Quincey made opium sublime and, in a word, romanticised it. His writing combined the monumental introspection of William Wordsworth, still new, with the drug-doom of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and stirred them together with a large dash of his own charm. The result made opiates seem intrinsically bound up with what he elsewhere calls “secret haunts of feeling”; “that inner world, that world of secret self-consciousness, in which each of us lives a second life.” It is thanks to De Quincey that John Updike could refer casually to “the writer in his opium den”, by which he means any sensitive modern writer in creative privacy: opium has become a metaphor, a quintessence of subjectivity itself.

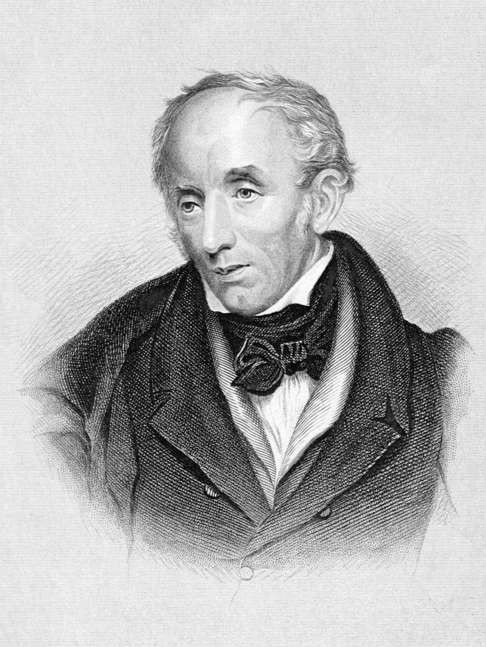

William Wordsworth. Illustration: Corbis

De Quincey’s shifting relationship with Coleridge and Wordsworth, particularly the latter, is central to the book. He began as a young fan, writing a list of poets he admired and putting three exclamation marks after Wordsworth’s name, and graduated to become his hero’s friend, lodger and dogsbody. Finally it all ended in resentment and hatred, after he had failed to make a sufficient impression on Wordsworth’s elephantine ego. Of all the pains De Quincey suffered with the Wordsworth family, mostly slights and disrespect, the worst was the infant death of Wordsworth’s daughter Catherine. She seems to have had Down’s syndrome and De Quincey doted on her. His grief when she died was so severe that for a couple of months he lay down nightly on the grave, and it appalled some witnesses: Henry Crabb Robinson , another figure in the Wordsworth circle, thought there was a “womanly weakness” about it.

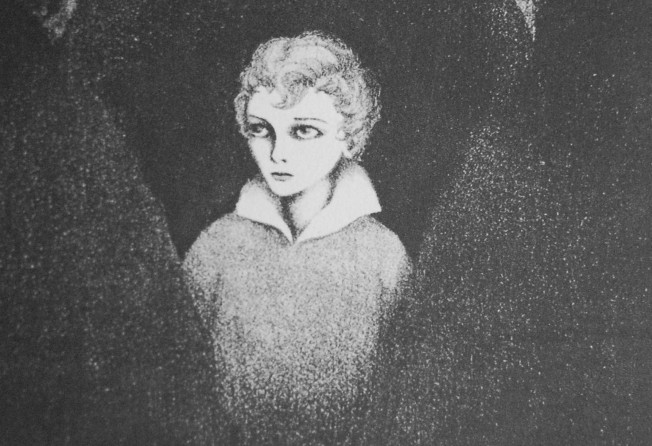

De Quincey’s fate was sealed not when he first took laudanum, but when his nine-year-old sister Elizabeth died when he was six. There was something sacred about sisters for him, and the poem that first attracted him to Wordsworth was the somewhat mawkish We Are Seven – where the number stands not for age but for the siblings a little girl insists are in her family, when in reality only five are still living. Lost girls, dead girls and brother-sister friendships were lifelong obsessions for De Quincey, particularly in the case of Ann, the child prostitute who befriended him in London after he ran away from school. He left town to borrow money and they arranged to meet again at the corner of Great Titchfield Street, but when he returned Ann was not there. London was already so vast and anonymous that he never found her again or discovered what had happened to her: “If she lived, doubtless we must have been sometimes in search of each other, at the very same moment, through the mighty labyrinths of London: perhaps even within a few feet … amounting in the end to a separation for eternity.”

Illustration of opium smokers in the East End of London from the London Illustrated News, 1874.

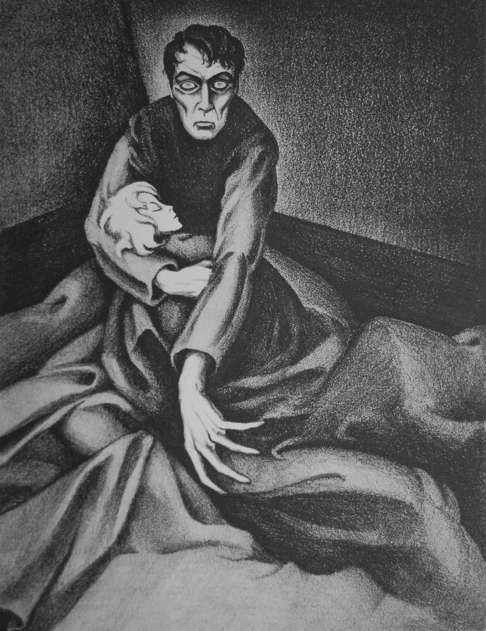

Everything recurs in De Quincey, and the theme of a girl in danger comes round again in his essay The

English Mail-Coach, recounting a journey – he liked to sit on the outside, with the driver, after dosing himself with laudanum – going at a breakneck gallop, when he realised the driver was asleep: and not only couldn’t he be woken, but the coach was bearing down like a juggernaut on two young lovers in a fragile carriage, and they didn’t seem able to hear De Quincey shouting until it was almost too late. In a coda to the essay,

The Dream Fugue, this already dreamlike episode comes back further transformed into nightmare, when he is on board a triple-decker warship bearing down on a girl in a boat. As Wilson says: “The unknown woman joined the gallery of girls whose deaths he had been unable to prevent” and she goes further in seeing the piece as a precursor to JG Ballard’s

Crash.

Ballardian or not, De Quincey was a pioneer in sensationalism, and Wilson’s other great theme is his obsession with murder, explored in successive versions of On Murder. This begins as a satire on the idea of the “aesthetic”, newly arrived from German philosophy, but De Quincey warms to his theme a little too enthusiastically, particularly when he gets his teeth into the Ratcliffe Highway murders. Murder also gave De Quincey the chance to indulge his arch sense of humour, with homicide as a slippery slope: “for if once a man indulges himself in murder, very soon he comes to think little of robbing; and from robbing he comes next to drinking and Sabbath-breaking, and from that to incivility and procrastination.”

Artwork from Confessions of an English Opium Eater.

More than opiates, the intoxicating thing in De Quincey is his writing itself, with its soaring heights and abyssal depths – a verticality that made 19th-century critic Leslie Stephen think of the rising and plunging of a bat, an appropriately gothic creature – and its sense of “involutes” or emotional constellations, as in his profound insight that “far more of our deepest thoughts and feelings pass to us through perplexed combinations of concrete objects, pass to us as involutes (if I may coin that word) in compound experiences incapable of being disentangled, than ever reach us directly, and in their own abstract shapes … ”

This is a superb book, more tangly, obsessive and excitable than previous biographies, and in that sense more in tune with its subject. It is packed with interest from the early days in Bath with his mother (where by strange chance they lived in the house that Edmund Burke , great theorist of the sublime, had just left) to the last debt-ridden days in Edinburgh. Finally, in the words of his daughter Emily, as “the waves of death rolled faster and faster over him” he suddenly rose as if from an “abyss” with his arms in the air and the words “Sister! Sister! Sister!” He died as he had lived, in character to the end.