Memoirs of cancer: how facing up to the worst can sometimes bring out a writer’s best

Memoirs about fighting terminal illness are not light summer reading, but books by Paul Kalanithi, Jenny Diski and Marion Coutts chronicling the final countdown are beautiful and moving works

A memoir of cancer – by an author who has since died of the disease – is an unlikely bestseller. Yet here is Paul Kalanithi’s When Breath Becomes Air, still hovering near the top of American non-fiction lists six months after it was published.

Light summer reading this is not: Kalanithi, a gifted neurosurgeon, was diagnosed with stage IV lung cancer when he was just 36 years old. He describes flipping through his CT scans, at once doctor and patient: “The lungs were matted with innumerable tumours, the spine deformed, a full lobe of the liver obliterated,” he writes. “Cancer, widely disseminated.”

Despite the grim subject matter, you can see why When Breath Becomes Air has struck a chord with readers. Kalanithi is a lucid, likeable narrator. The book is as much about his life’s journey of self-discovery as it is about illness and death; he got a master’s degree in literature before undertaking the rigours of medical school. Driving all his education was the quest for a deeper “understanding of the relationship between meaning, life, and death”.

But the book isn’t just an intellectual exercise. His writing about cancer – refracted through his marriage to Lucy, a fellow doctor, and the birth of the daughter he will hardly know – is unbearably sad. The slim, unfinished volume is bookended by a foreword by physician-author Abraham Verghese and an epilogue by his widow. Like Kalanithi’s life, it feels incomplete but rich with significance.

“Well, I suppose I’m going to write a cancer diary,” Jenny Diski remarked the very day she received her diagnosis (inoperable lung cancer). As she ruefully observed in the opening passages of In Gratitude: “Can there possibly be anything new to add? Isn’t the cliché of writing a cancer diary going to be compounded by the impossibility of writing in it anything other than what has already been written, over and over?”

Maybe so. But nobody had a voice quite like Diski’s. The novelist and memoirist, who died in April, was a longstanding contributor to the London Review of Books, where said diary first appeared, and her prose crackles with irony and intelligence. (Sample line: “Really, there is nothing I want to do before I die, except perhaps just lie back and enjoy the morphine, daydreaming my way to oblivion.”)

Though Diski writes bracingly about the failures of her body and the indignities of treatment, the most fascinating section of the memoir concerns her thorny relationship with Nobel Prize-winning novelist Doris Lessing, who took her in when she was a troubled teen expelled from school and abandoned by her dysfunctional parents. Through it all, you have the sense of Diski turning her life over and over in her lively mind, writing it all down to figure out what she thinks.

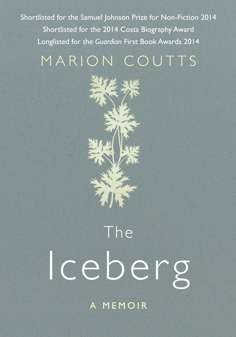

If Kalanithi and Diski were writing on the most unforgiving of deadlines, Marion Coutts had the bittersweet luxury of time as she crafted The Iceberg, a memoir of her last three years with husband Tom Lubbock, an art critic for The Independent newspaper, who died of a brain tumour in 2011. The book, Coutts’ first, is astonishing: poetic, philosophical, dense with ideas and emotions.

“How many times do I think, Now we are really in trouble,” she writes after the latest round of Tom’s chemo appears not to be working. “Well, on this page I say it again. Now, we are really in trouble. And this time I mean it more than all the previous times. But there will surely be another time when I will mean it more still and this time will seem as nothing.”

Two surgeries, different chemotherapies – nothing stops the tumour’s growth. It begins to impair his mobility, his linguistic abilities. “Tracking elusive words was always Tom’s pleasure,” Coutts writes, “but now it has added urgency.” Through it all he presses on with his writing.

Meanwhile, Coutts tries to make a normal life for their young son, here called Ev. The boy runs wild through these pages, “an island boy to our city dwellers”. At the end of an especially rough week for Tom, she writes, Ev is “smiling and relaxed, happy and about to sleep. I believe him. He does not dissimulate. What a wonder.”

Even as Tom loses words, Coutts finds the ones she needs to tell her story: “All I can do is put one word down after another and rearrange them so that you might have a sense of what they mean,” she says. With The Iceberg, she succeeds beautifully.