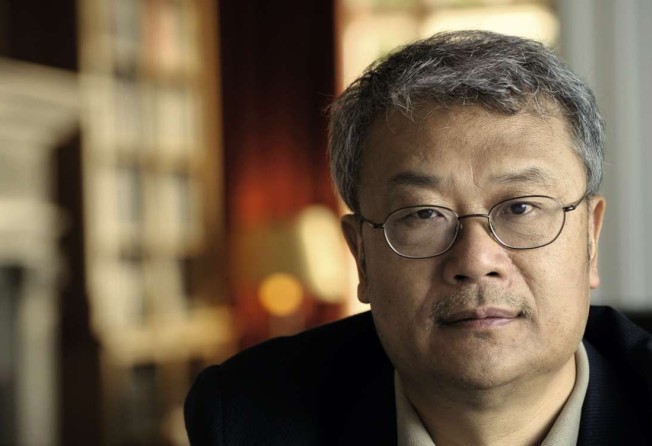

Book review: In Ha Jin’s choppy Boat Rocker, a journalist takes on China

More a screed taking aim at the various permutations of Chinese censorship than a novel, the poorly constructed and executed Boat Rocker flounders

The Boat Rocker

by Ha Jin

Pantheon

2.5 stars

“You’re like a little turtle attempting to rock a boat shared by two huge countries.”

Hence the title of Ha Jin’s The Boat Rocker, in which the so-called turtle is 36-year-old Feng Danlin, a journalist working on Long Island for a small Chinese news agency that’s trying to speak truth to power back home in Beijing.

Easier said than done, which is why Danlin is being lectured by a Chinese consul, making clear that if Feng continues rocking the boat with his current series of columns, there’ll be significant consequences – never mind that this onetime Chinese national has recently become a US citizen.

One wouldn’t think Danlin’s columns could cause such consternation; they involve a takedown of Love and Death in September, a soon-to-be-published Chinese romance novel penned by Yan Haili – none other than Danlin’s ex-wife, who’d unceremoniously dumped him when he’d followed her to America seven years earlier.

But some heavy hitters in the Chinese cultural establishment have thrown their weight behind the novel; packaged with its attractive, pro-China author, they see it as a means of advancing China’s cause in the West.

Would that any novel in this era could actually cause these sorts of waves; in a clunky plot filled with improbabilities, this might be the hardest one to swallow. It’s much easier to believe that Beijing would put the screws to a journalist – regardless of origin or citizenship – suggesting that when it comes to culture as with speech, China is less interested in freedom than its image.

Unfortunately, Ha Jin the multiple award-winning Chinese writer of novels such as Nanjing Requiem – seems less interested in writing a novel than a screed taking aim at the various permutations of Chinese censorship – and how they thwart intellectuals’ efforts to speak their minds, which become “docile and atrophied” by trading “principles” for “perks”.

There’s a nearly Orwellian aspect to Danlin’s lonely struggle to hang tight to what he believes, even as those around him follow the footsteps of his onetime wife, sacrificing youthful idealism for power and prestige. “I felt like Don Quixote,” he tells us, “charging at windmills with a broken lance.”

Danlin’s quest – often less heroic than priggishly self-righteous – results in some wooden, ideologically charged dialogue. Here’s an illustrative example, involving an exchange between Danlin and a woman who remains loyal to Beijing:

“The truth,” Danlin insists, “is that a country is not a god, it’s a historical construct. It’s foolish to imagine a country as a mystical figure, a generous mother that has raised all the Chinese, who in turn must remain obedient, longing for her love and nurturance. That’s a fallacy, a lie.”

“Wait a second,” his companion responds, interrupting Danlin’s harangue with one of her own. “I object! I believe we must maintain the distinction between the country and the ruling power, just as I love China but hate the Chinese government. Shame on you for what you just said.”

Such exchanges – and they’re legion, in this novel – are lifeless. Worse, they stifle potentially more interesting but ultimately undeveloped ideas that are introduced and then dropped.

How, for example, is Danlin’s high-minded crusade compromised by his acknowledged thirst for revenge against an ex he describes as a “brassy b****,” who he claims he wouldn’t forgive “even if she begged me on her knees”? What does one make of Danlin’s consequent ambivalence towards women, sexuality, marriage and children?

What is the relationship between aesthetic merit and the often cutthroat bookselling business – not just in China but throughout the world? A related question: why does Danlin periodically ruminate on carpentry and solid craftsmanship, in a novel nostalgic for an era when people as well as buildings – like the one he watches go up – were made of stronger stuff?

Recollecting infinitely better Ha Jin novels, this poorly constructed and executed book induces such nostalgia.