Book review - Wartime Macau: Under the Japanese Shadow investigates the precarious freedom of a neutral enclave

Macau was never occupied by the imperial Japanese forces and remained a safe haven in a war-torn region, but information on this period has been hard to come by in English, making this volume all the more appreciated

Wartime Macau: Under the Japanese Shadow

edited by Geoffrey C. Gunn

Hong Kong University Press

4/5 stars

Macau is endlessly fascinating in no small part because it is so anomalous. Dating back to the “Age of Exploration”, it was the only Iberian possession in East Asia that survived as such into the 20th century – and remained in European hands two years longer than Hong Kong did.

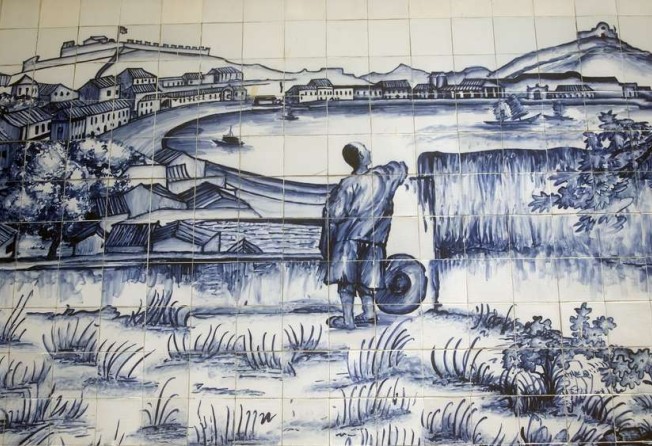

In spite of all the recent development, it is still a city of baroque churches, blue tiles and black-and-white pavements; streets are ruas; a local Portuguese patois unique to the city still just hangs on.

Macau is often contrasted with the much larger Hong Kong. Already sliding into obscurity when Hong Kong was founded, Macau soon became and remained the junior of the two foreign-run municipalities. Hong Kong ran on banking and trade, Macau on gambling. Many Macanese set up in Hong Kong, while Macau was often considered a somewhat dissolute weekend playground.

But perhaps most strikingly, Macau escaped Japanese occupation during the second world war due to Portugal’s neutrality. Hong Kong’s war years have been the subject of countless studies, novels and films, but information on Macau – especially in English – has been much harder to come by.

With the exception of The Lone Flag: Memoir of the British Consul in Macau during World War II, also published by Hong Kong University Press, Wartime Macau: Under the Japanese Shadow might be just about it.

Although Wartime Macau is a collection of contributions from several authors, perhaps half the material is provided by the editor, Geoffrey C. Gunn, lending the volume more coherence of style and focus than can be the case in such books.

Whether by accident or design, Wartime Macau’s combination of the personal and political stimulates intellectually and emotionally. The intellectually satisfying moment comes with Gunn’s discussion of how Macau fitted into the geopolitics of the war.

It is too simple to say that Portugal was neutral, that therefore Macau was considered neutral territory and the Japanese respected it. Neutrality was not enough to spare East Timor, for example: Japan invaded to expel a small group of Australian, British and Dutch forces that had installed themselves there. Japan never left. Portuguese protestations had to stop short of a declaration of war because Macau would have been immediately occupied.

The Allies, meanwhile, were concerned about Portugal’s vulnerability and were angling for base rights on the Azores. Germany didn’t want Portugal to tip into outright Allied solidarity. António de Oliveira Salazar, the Portuguese leader, was working to preserve Portugal’s colonial possessions in the future post-war period. The resulting unstable equilibrium contributed to preserving Macau’s precarious autonomy: it was a close thing at times.

Similarly interesting, if less far-reaching, is the discussion of the role that Banco Nacional Ultramarino played in maintaining some semblance of financial stability at a time of multiple fluctuating currencies.

The hero of the book, if such a book can be said to have had one, is the governor of the time, Gabriel Mauricio Teixeira, who managed to keep the place going despite food shortages and a dramatic influx of refugees which more than doubled Macau’s population. Macau seems, at least by today’s standards, to have been remarkably generous.

Teixeira also had to contend with the murder of the Japanese consul, the bombing of Macau by the Americans, and other incidents which could have brought an end to the enclave’s fragile independence. Other personalities also make their appearance: British Consul John Pownall Reeves, businessman and philanthropist Pedro José Lobo and, of course, casino mogul Stanley Ho.

Macau deserves rather more respect than it sometimes receives. When a conflict has such clearly etched antagonists as the second world war did, it can sometimes be hard to see neutrality as a virtue. But Macau was neutral and the many who benefited from the resulting relative safe haven were no doubt glad that Macau worked so hard to maintain it. And we should be glad it has been chronicled in such a conscientious and heartfelt manner.

Asian Review of Books