Hong Kong in a period of change and danger, ex-city academic and writer Madeleine Thien warns

Everything’s on the table for city in this time of transition, says Chinese-Canadian author who taught in Hong Kong for five years and calls herself a reluctant commentator on Chinese affairs

Madeleine Thien stands at a small podium facing a long line of fans who are waiting for her to sign their books. It is midway through this month’s Macau Literary Festival and she has just finished a talk about her latest novel, Do Not Say We Have Nothing. Eventually, every book has been graciously signed and Thien, a slight, elegant figure, steps down from the stage with a smile.

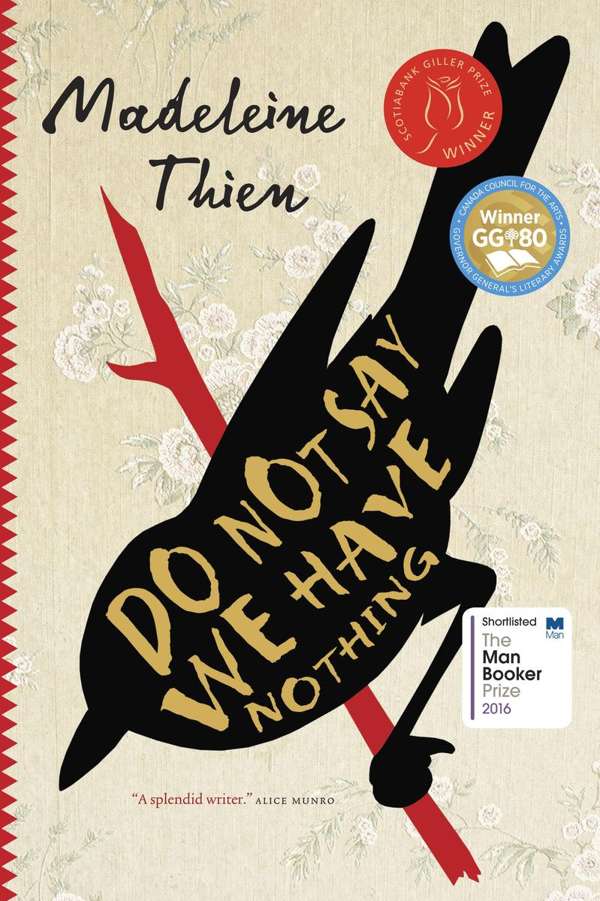

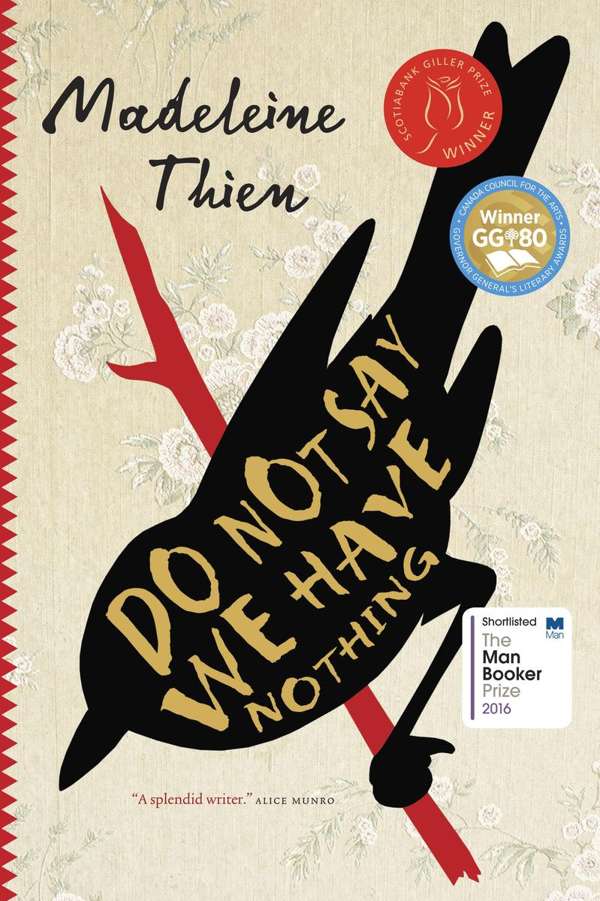

Thien has, naturally, talked a lot about her book since it was shortlisted for the Man Booker prize as well as winning a host of other literary awards. Do Not Say We Have Nothing tells the story of several generations of a family of musicians adjusting to the havoc wreaked on their lives by the Cultural Revolution and Tiananmen Square.

Many of the questions she was asked in Macau concerned politics as much as prose. Given that the book is about two of the most highly charged periods in China’s recent history, Thien, a Canadian, is frequently seen as a commentator on China. It’s not a role she particularly welcomes.

“When the political questions come, it’s in my nature to answer as best I can, but there is a part of me that is wondering, ‘Should I sidestep the question?’” she says.

Whatever desires were expressed in Occupy, they haven’t gone away. They are there, and it’s very unpredictable how it’s going to manifest

She answers them because she feels deeply connected to China and cares about the country, she explains. “I have never seen China and Canada – the different parts of myself – as two actual sides or poles,” she says. “They’ve always been overlaid one on top of the other. They’re always part of the same fabric.”

Thien’s Hakka father and Hong Kong mother moved to Vancouver a few months before Thien was born and she grew up as the only native English speaker in her family. That rich background has helped set the scene for some of her books. Thien now lives in Montreal, but her novels are centred on Asia and she has spent a lot of time in the region researching them. Her first novel was about Malaysia, her father’s home, the second was about Cambodia, and much of Do Not Say is set in China, as well as in Canada.

As her mother’s birthplace, Hong Kong has always had a strong pull for Thien. She lived here for five years, teaching on City University’s now-defunct master’s programme in creative writing and says she would happily return.

“[Hong Kong] is in a time of transition,” she says. “A place in transition has so many possibilities as well as so many dangers. Everything’s on the table in a way that it isn’t in more stable societies.”

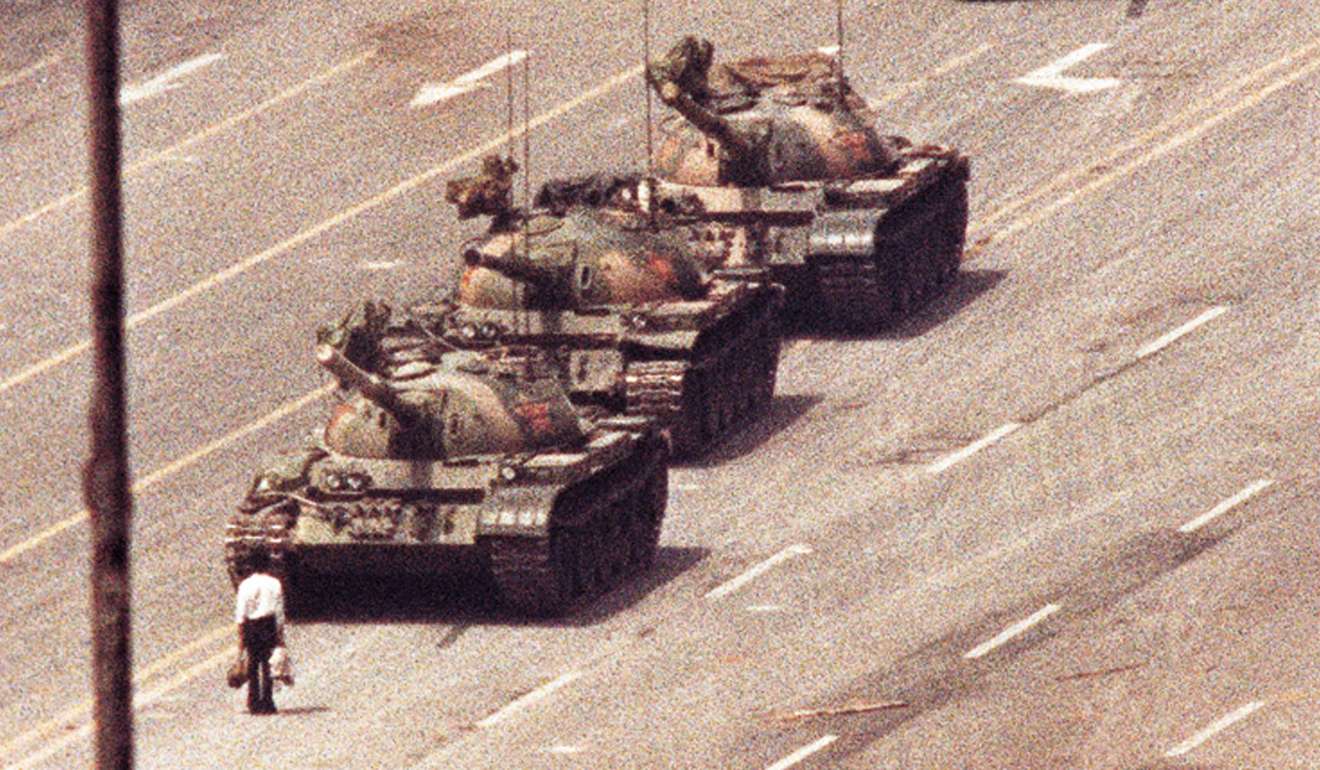

Unstable societies are a recurring theme for Thien. Dogs at the Perimeter, published in 2011, dealt with Cambodia’s genocide. Her original plan for Do Not Say was a short book about Tiananmen, but it became a longer and more expansive story after she became intrigued by the 40- and 50-year olds who came out to protest alongside the students. Thien realised that many in this older generation had lived through the Cultural Revolution and she saw a connection in the continuing idealism between the two generations.

“Because to understand 1989, I think you really have to understand what came before,” she says.

The potential similarity with the unfolding of Occupy in Hong Kong was not lost on Thien and she says she watched anxiously to see how far the protesters would go and how the government would react.

“Whatever desires were expressed in Occupy, they haven’t gone away,” she says. “They are there, and it’s very unpredictable how it’s going to manifest.”

She also followed the disappearance of the Hong Kong booksellers, which she sees as another sign of the “tightening” in the city, but not one that is necessarily linked to her book’s lack of a publisher here or in mainland China so far.

“There is definitely a chill in Hong Kong publishing and bookselling,” she says. “That is in addition to the normal commercial pressures that there are on booksellers and publishers. I get the feeling that people are still feeling their way forward. And this is a sensitive book.”

Hong Kong stores used to sell books offering a variety of political viewpoints, she says. “That availability of ideas is the sign of a healthy political structure,” she says. “The more that begins to narrow in, it is part and parcel of greater control over permissible ways of thinking about the situation.”

Do Not Say was not written with a particular audience in mind, or indeed, with hopes of much of an audience at all. “I didn’t think about it,” she says, with a slow smile. “You’re writing about something because it troubles you, so you’re just trying to get to what is deeply troubling your philosophical or moral self. That is where all the energy goes. I think I was protected because there hadn’t ever been a big audience for my books, so there was no expectation that there would be one.”

Her previous two books took her five years each to write. Although both dealt with particularly grim topics and times, Thien says that, looking back, she can see that the impetus that lay behind them was mainly positive.

“In a way, the impulse of the novels is very much about imagining our way back into these decisive moments and trying to see even momentarily what other possibilities were available, because it is a forking of the road, almost,” she says. The events of 1989 could have taken a very different turn, she says.

“It’s tracking those missed opportunities so that we can come to the present moment not feeling as if the worst-case scenario or the things that we fear are inevitable.” She pauses. “In this funny way, I think I am quite melancholic, but the novels are ways of – I never thought of it this way before – but they’re almost about being more prepared to live in the present.”