Singapore before colonisation: from Temasek to Singapura, destruction, and flight to Melaka and Johor

- Pre-Raffles history involves the Srivijayan and Majapahit empires, Portuguese and Dutch colonists, Acehnese, Bugis and Orang Laut

- New book Studying Singapore Before 1800 gauges the impact of early globalisation and ponders whether a lion gave Singapore its nickname

Studying Singapore Before 1800, edited by Kwa Chong Guan and Peter Borschberg (National University of Singapore Press). 3.5 stars

The history of Singapore before the foundation of the modern version of the city by Sir Stamford Raffles in 1819 has been largely ignored.

This volume of 18 articles (with a wide range of original publication dates) looks to rectify this and show that Singapore, because of its strategic location on the shipping route between East and West, was heavily involved in pre-British waves of global trade and colonisation.

Co-editor Kwan Chong Guan explains why this matters: “The challenge for Singapore in the 20th century is to recognise the nature of the post-colonial or postmodern cycle of globalisation it is caught in, and to decide best how to respond to it. Looking at the impact of earlier cycles of globalisation on the maritime history of the Melaka Straits may provide Singaporeans with a better understanding of their city state’s vulnerabilities.”

The sources regarding this early history are not easy to interpret. The Malay Annals (Sejarah Melayu), for example, are a mix of history and myth, and need to be compared with accounts of Chinese traders in the region.

Understanding the history of the region, with a focus on Singapore, is no mean feat, but over the course of these 18 articles the reader can begin to put it together.

Key to the narrative is the establishment of the kingdom Singapura in the 14th century by a Srivijayan prince from Sumatra.

One of the many issues up for dispute is whether the name Singapura (meaning “Lion City” in Sanskrit) came from the sighting of a lion or lion-like creature on the island, which originally had the name of Temasek. There have never been in lions in the region.

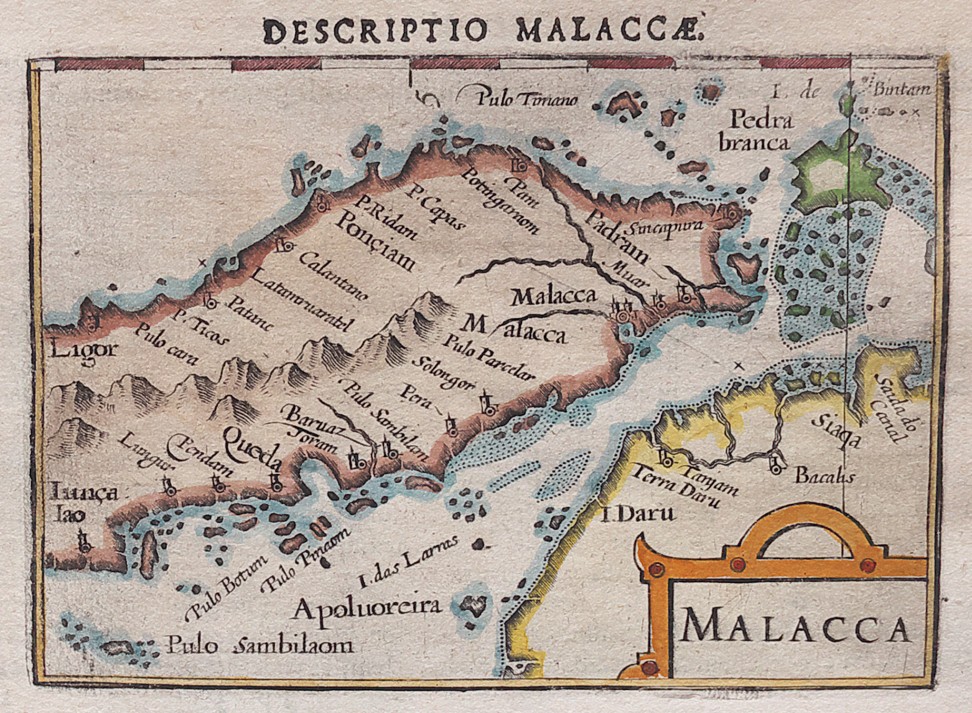

Singapura was destroyed by the Hindu Majapahit Empire, and the inhabitants moved on and formed the city state of Melaka (Malacca). The banished king of Singapura, Iskandar Shah, converted to Islam and Melaka became a flourishing Malay city state and trading hub.

It was conquered by the Portuguese in the 16th century. After this the Malays of Melaka founded the Johor kingdom – it was with one of the Johor sultans that Raffles later negotiated to acquire rights to the island of Singapore for the British.

In the interpretation of the sources, the scholars writing in this volume don’t hide the fact that there are unanswered questions. For example, who exactly was it who laid waste to the 14th-century version of Singapore in about 1377? It could have been the Majapahit already mentioned, but Portuguese sources point towards it having been the kingdom of Siam.

Portuguese dominance in the region, never complete, later gave way to the Dutch. Several Dutch articles appear for the first time in English in this book. Also on the scene were the Acehnese of North Sumatra, Bugis of Sulawesi and then perhaps most interesting of all, the Orang Laut or sea people.

The Orang Laut were alternately loyal subjects of Melaka and Johor and pirates who terrorised merchant ships. They often lived on their boats and were present in every part of the region.

In a particularly enjoyable essay on 17th century Malay power structures, contributor Leonard Y Andaya writes: “The duties of the of the Orang Laut were to gather sea products for the China trade, perform certain special services for the ruler at weddings, funerals, or on a hunt, serve as transport for envoys and royal missives, man the ships and serve as a fighting force on the ruler’s fleet, and patrol the waters of the kingdom.”

A lot of ground is covered in the book and these articles are great secondary source material for the serious historian.

Some of the content gets quite far away from Singapore and the number of ethnicities and kingdoms involved in telling this history is a bit overwhelming.

In the end, the story of Melaka comes through as equally fascinating as that of Singapore – if not more so. The introduction by editor Kwa Chong Guan makes a valiant attempt to give a solid overview of the topic at hand, and to hold this volume together. The plentiful illustrations, including maps, photos and paintings, also add greatly to this book.