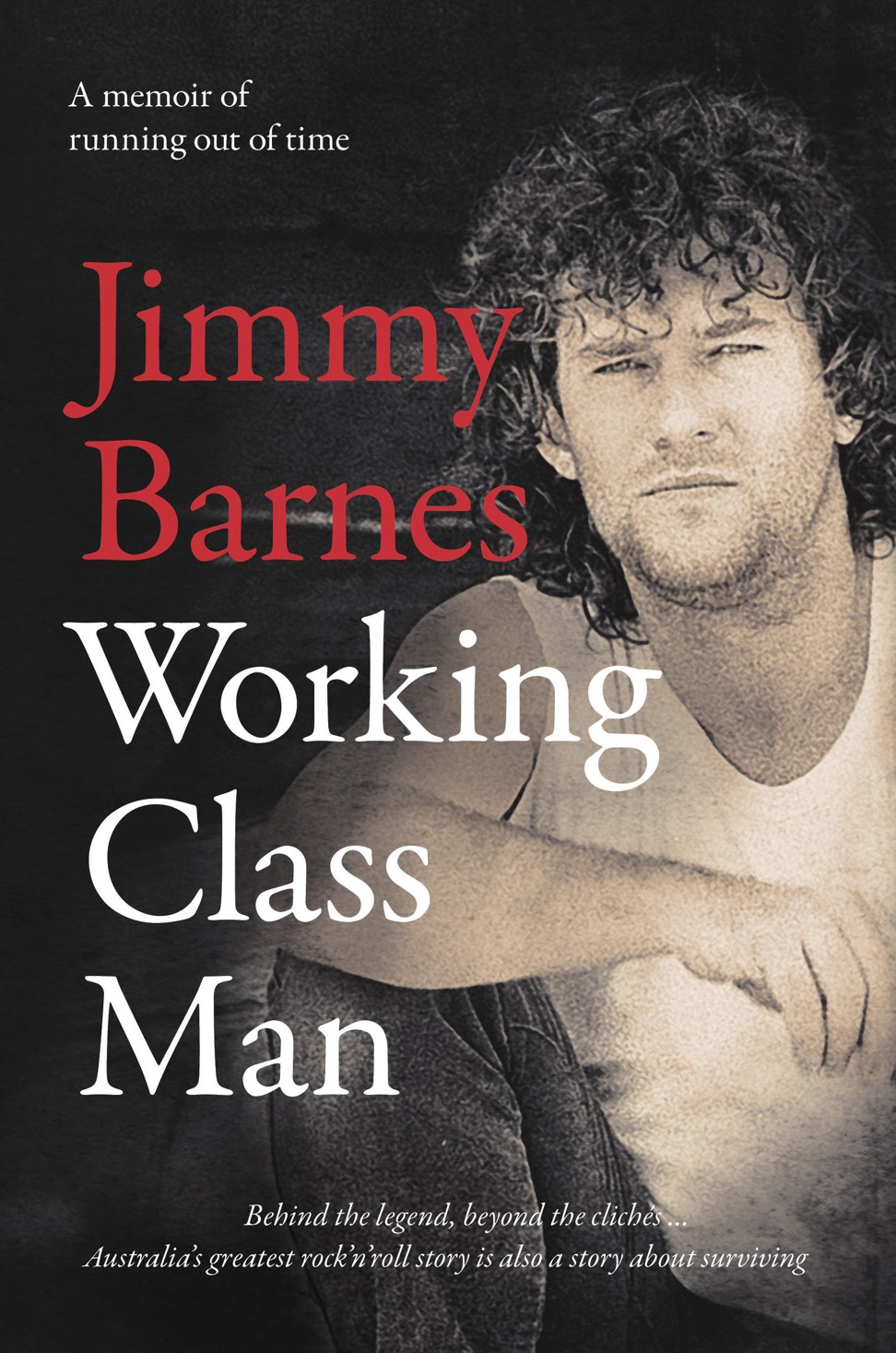

Jimmy Barnes won’t go down without a fight: Cold Chisel frontman faces his demons

The Australian rock star’s second memoir, Working Class Man, tells how for 40 years he tried to ‘drink himself to death’, only to finally see the light. Catch him at the Parisian Macao on December 9

When Jimmy Barnes shakes your hand, he’s scoping your knuckles. Are they split from fighting? Just how big is your hand, anyway?

“I’m friendly but I’ll want to have my back to the wall. I know where all the exits are and I’ll know who I have to hit if I want to get out,” says the former frontman of Australian rock band Cold Chisel, who’ll be performing a solo show at the Parisian Macao on December 9.

Don’t get him wrong; Barnes is known for his geniality. He’s light on his feet (like a boxer, like his dad), ready to smile, and has a patience with journalists quite unbecoming to a rock singer. But that hyper-vigilance he learned in childhood has never left him.

Barnes was the household name no one expected to get real about domestic violence. His first memoir, Working Class Boy, shocked even his own bandmates when it was published last year. It’s a graphic account of a childhood steeped in neglect, abuse and abject poverty. In the 1950s, his family migrated from Glasgow to a close-knit Scottish community in Adelaide’s Elizabeth. Close-knit, because no matter how many mums had black eyes, you didn’t embarrass each other by talking about it.

“For 40 years, in front of the public, I was drinking myself to death,” Barnes says. “If you did that in any other job, people would say, ‘You’ve got problems, mate.’ But people didn’t see it like that because they were living vicariously through me.”

The 17-year-old who joined Cold Chisel was an incendiary hothead, wired to take offence. He never paused to consider the childhood he was escaping. In fact, he was running full tilt, leading with his fists. “I’m homicidal, not suicidal,” he’d joke to himself. As he observes now: “If anything hurt me emotionally, I’d want to belt someone. That was my take on life in general: I’m not wounded, I’m the aggressor.”

Harnessed on stage, this fury made Chisel a live band to be reckoned with. It’s unsurprising Barnes made them his new family, having had his blood family shattered when his mother left. “The best times in Cold Chisel were when we were all in the back of the car together, us against the world,” he says of his contentment playing the roughest pubs in the country. “It wasn’t about ambition. It was about having a sense of belonging and freedom.”

It fell to songwriter and keys man Don Walker – who was in the middle of an honours degree in quantum mechanics – to play big brother and manager, and he’s the voice of reason throughout Working Class Man; the third-party conscience, even. “Poor Don,” Barnes says sincerely. “Whenever it fell apart he’d be the guy who had to pick up the pieces. He’s still the big brother; that’s been the dynamic of the family. These days we all pull our weight more but we look to Don for the final decision making.”

It was on the road that Barnes first met his wife, Jane Mahoney, and, make no mistake, Working Class Man is also a love story. “I can remember the minute that I seen Jane,” he says. “Four in the afternoon, the 29th of November, 1979. She was so beautiful, I literally had to walk out of the room and regroup. Throughout all the highs and lows over 38 years, I still pinch myself and think I lucked out big time.” The scenes in which Barnes journeys to Japan to impress the affluent expat in-laws are as howlingly well-described as his later collaborations with spandex-wearing, latte-chugging LA songwriters.

Once he’d established a young family (who all, he says, inherited his impulsivity), Barnes broke away from Chisel at the height of their popularity. He was furious at not seeing enough of the profits for his liking. Some band members might have derived a sense of romance from living in dilapidated hotels but, as he says: “I’d seen enough filth and desperation.”

Barnes is frank in his admission that much of his ensuing 35-year solo career was fuelled by his desire to live up to Chisel. “For a long time, it was all about chart position,” he admits. “‘If my record doesn’t come in at No 1, I’m a failure.’ I cared too much about what people thought of me, and that was symptomatic of the trauma from my childhood.”

He’s since had to reassess his definition of success, with the painful knowledge that it’s possible to have five No 1 albums in a row and also face bankruptcy. “Success isn’t about reaching your goals, it’s about striving for things, like the joy of trying to raise a family, trying to be a successful singer, trying to write good songs, trying to be a better person,” he says. “It’s that old thing about life being about the journey, not the destination.”

Such wisdom is hard-earned, from decades of chasing peace. In 2000, at a time he was snorting 10 grams of cocaine a day and relying on whisky for sustenance, he would jump in a limo and get dropped off at the new age guru Deepak Chopra’s clinic in San Diego. “He’d pump me full of vitamins and have people standing me up and stretching me,” he recalls. “He’d talk to me about ‘why are you doing this to yourself?’ Then they’d put me back in the limo and I’d go back to the studio and do it all again.”

Then there was the time spent at the Wat Pa Tham Wua monastery in northern Thailand, where he cooked vegetarian pasta for 1,000 monks, straining it in mosquito nets. “Nah, it didn’t help me,” he says, laughing, “but I learned stuff and it probably kept me alive.”

But it is playing live that gives him an almost spiritual sense of connection, he says.

“It feels like an out-of-body experience. There’s something about the energy and the expectations that an audience projects at you. I get up on stage and work and work, and there’s chaos all around me, then I’ll shut my eyes and boom! I slot into the zone. It’s like the eye of the hurricane. Everything is easy, and I’m capable of doing things I didn’t know I was. That’s what you chase. You want to be in there all the time.”

These days, that comes with a bonus: “I haven’t had to fight anybody for years.”

Jimmy Barnes, Dec 9, 9pm, Parisian Theatre, Parisian Macao, Cotai Strip, Macau, HK$380-HK$780, HK Ticketing