Tianjin’s foreign investment and jobs drop amid trade war and industrial shift to new sectors

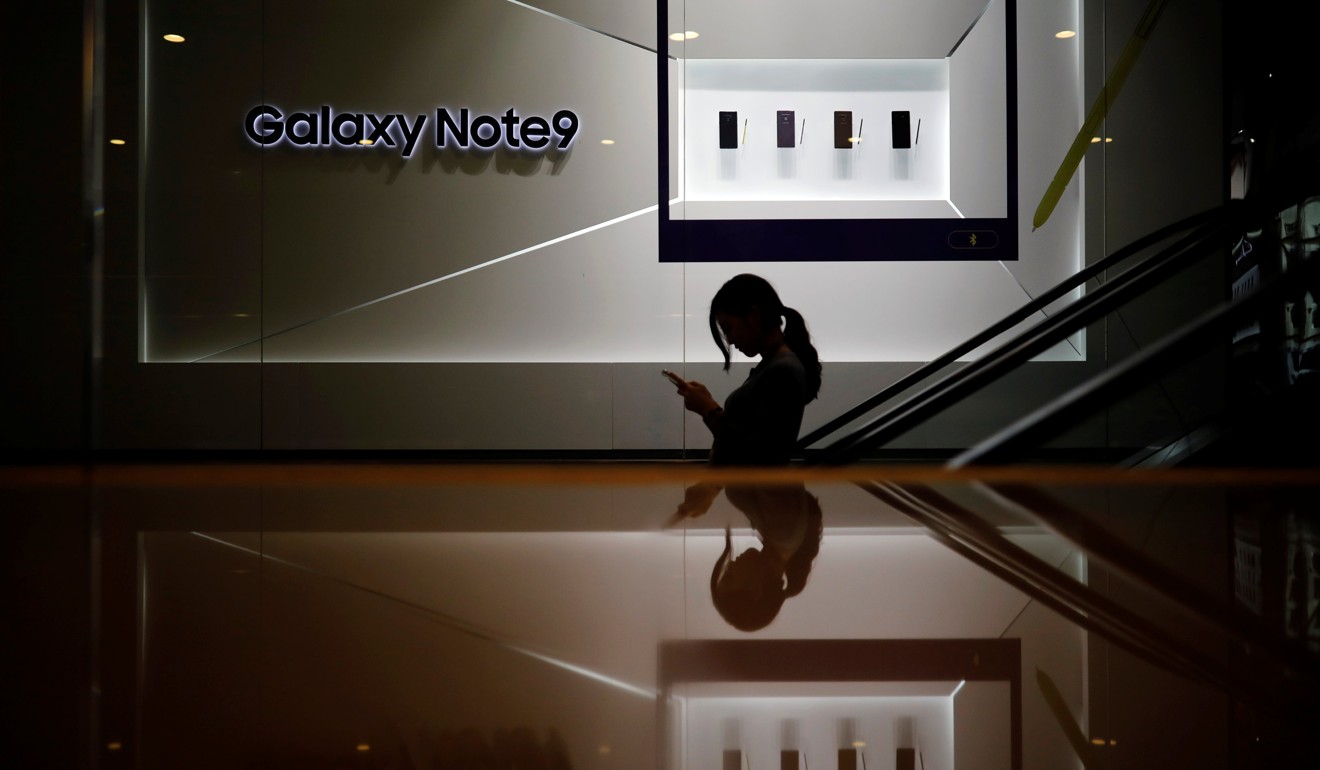

- Closure of Samsung’s huge smartphone factory in December highlights the challenges faced by foreign firms in China’s fast-evolving business environment

- Total foreign direct investment in Tianjin last year plunged to US$4.85 billion from US$10.61 billion in 2017; gross domestic product growth fell to 3.6 per cent

With the Chinese economy slowing, concern has increased among Chinese policymakers about the outlook for employment, since ensuring a sufficient number of new jobs is seen as a necessary ingredient in maintaining social stability in the country. Employment was the top priority the Politburo set last July when it shifted its economic policy focus to stabilising growth. That led the government to enact a series of policies to counter rising joblessness. This series explores the employment challenges faced by different segments of the Chinese economy; this fourth instalment examines the challenges faced by foreign firms.

For residents of the city of Tianjin in northeastern China, the closure of the huge Samsung smartphone factory in December symbolised the end of an era for the South Korean electronics giant, which was once the most popular brand in China.

The closing points to the challenges faced by foreign firms in China’s fast-evolving business environment as they go up against well-subsidised domestic competition, and the problems this presents for the thousands of people they employ.

It also highlights two major trends in the manufacturing industry in China: the shrinking of low-cost production due to rapidly rising costs and the push by the government to advance domestic high-end manufacturing.

Foreign firms cut back their investment in Tianjin sharply last year, amid the uncertainty created by both the US-China trade war and the companies’ search for lower-cost production outside of China.

The Samsung factory site, located in the port’s Xiqing district, which had been developed by the Tianjin government specifically to attract foreign investors, had been in operation since 2001.

The electronics firm said in December that the closure would lift the overall efficiency of its business in China, adding that it had reached compensation agreements with 90 per cent of its 2,600 employees.

“There aren’t many people here now,” said a security guard at the locked and deserted site.

“Those few you saw walking past are mostly staff cleaning up what’s left.”

Businesses that served the company’s employees have also felt the pain since the site ceased operations on December 31. “We used to get a lot of business ferrying customers in and out of the Samsung plant,” said one taxi driver. “The staff would come out for a smoke from the blocks where they lived and worked. Now it’s so quiet here.

“But it’s not really a surprise to me. I don’t see many people buying Samsung phones now. I have a Huawei phone myself. [Samsung] are not doing well here.”

Five years ago the South Korean brand was viewed by Chinese users as a technology and design leader, but over the past two years, no Samsung models have made it onto the list of China’s 10 bestselling phones.

Watch: Foxconn CEO Terry Gou pledges to invest in Tianjin, speaking in May 2018

Samsung is not the only foreign manufacturer to cut back on its investment in Tianjin, which has had a knock-on effect on employment.

For years, Tianjin was a popular location for foreign investors, with Japanese and South Korean manufacturers in particular attracted by supportive local government policies and low labour costs.

But since 2016, the city – which is located just over 100km (62 miles) east of Beijing – has been hit hard by a sharp drop in foreign investment, which has led to a slow-down in industrial growth and consumer spending.

Total foreign direct investment in Tianjin plunged to US$4.85 billion last year from US$10.61 billion in 2017 and US$10.1 billion in 2016, dragging down the growth rate in the port city, which had once been among China’s five fastest-growing large cities.

Gross domestic product growth in Tianjin fell to just 3.6 per cent last year and in 2017, well below the 9 per cent gain seen in 2016.

This decline of foreign investment has also had a significant impact on the local job market, according to Candice Wang, a consultant at RGF Human Resource Consulting in Tianjin.

RGF serves more than two-thirds of locally registered Japanese firms, but Wang said it has gotten increasingly difficult to find jobs for qualified workers in the city.

“The big picture is that Japanese firms waved goodbye to the good years a decade ago, and they have fallen behind European, American or even some Chinese peers,” she said.

When Wang joined the recruitment business five years ago, there was usually a long queue of applicants for both office and factory jobs. But this is no longer the case, as the monthly salary for entry-level university graduates has remained static at 3,500 yuan (US$520) for many years.

Foreign firms offering better reimbursement packages are having more success attracting qualified employees, with local workers flocking to better opportunities on Airbus aircraft assembly lines, in the Volkswagen car assembly plant or in the Amazon call centre, according to Wang.

“In many cases, we have to persuade human resources personnel to either lower their job requirements or raise the wage,” she said.

In a recent case, one of her clients had to offer 6,000 yuan (US$680) per month to hire an experienced security guard, well above the rate such a position would ordinarily offer.

Industrial downsizing among foreign manufacturers started in Tianjin in 2016 after Japanese semiconductor maker Rohm closed one of its two plants.

“I haven’t heard of a new opening of a Japanese factory” since then, Wang said.

China has been pushing hard to move its manufacturing industry up the value chain, as higher domestic costs for labour and land have caused many low-end manufacturers to consider moving to lower-cost countries in Southeast Asia.

Skyrocketing costs hit Samsung hard, squeezing its margins, and the company could no longer effectively operate in China.

According to a survey published on December 30 by the Japan External Trade Organisation, a government-affiliated think tank, 75.7 per cent of Japanese firms said rising wages was the top reason driving their businesses out of China.

A total of 53.5 per cent also pointed to regulatory challenges as the second most important factor when considering moving out of China.

The survey was conducted between October 9 and November 9 after the implementation of 10 per cent US tariffs on US$200 billion of Chinese products.

Responding to a question about their hiring plans this year, 64.2 per cent said they would maintain or reduce the current size of their workforce in China.

Overseas funded enterprises employed 25.8 million people in China in 2017, or 6.1 per cent of the total urban workforce, according to the National Bureau of Statistics, but this is already a large decline from its peak of 29.6 million, or 7.8 per cent, in 2013.

Foreign firms accounted for half of China’s total trade and a fifth of its tax revenue in 2017, according to a report titled “Foreign Investment in China” published by the Ministry of Commerce (Mofcom) in October.

Even though overseas companies are not employing as many people, they are better at job creation than local firms, according to the Mofcom report, which said that on average a foreign company hired nearly 3.7 times more employees than local firms in 2016.

Retaining and growing foreign investment is therefore key to steady employment and job creation, the report concluded, adding that China needs to enhance its position as one of the leading hubs for overseas investment.

“Since [Donald] Trump became [US] president, he implemented a substantial tax cut, greatly enhancing the attractiveness of the United States to cross-border investment,” Long Guoqiang, vice-president of the Development Research Centre of the State Council, said in an introduction to the Mofcom report.

“The [US tax] policy may trigger a new round of global tax cut competition, forcing countries to compete to reduce taxes to maintain or enhance the competitiveness of cross-border investment.

“In attracting high-end industries, [China] faces more intense competition and needs to prevent the withdrawal of foreign investment projects.”

Government officials in Tianjin seem to be listening, not least due to the slowdown in the city’s growth last year, and they were still able to keep Samsung as a major investor in the city.

Shortly before announcing the factory closure, Samsung said it would invest US$2.4 billion to build new battery and capacitor plants in Tianjin.

The Samsung investment also targets the rapidly growing electric vehicle market in China, which is part of the government plan to upgrade manufacturing.

In addition to throwing up new challenges for low-skill employees, high-value manufacturing also creates a new risk for cities like Tianjin: competition for a limited pool of highly skilled workers in advanced manufacturing industries.

“It is normal for foreign investment to come and go. Multinational enterprises are making readjustments globally, creating transfer of employment and re-employment of some workers,” said Ning Jizhe, deputy chairman of the National Bureau of Statistics.

As China’s share of hi-tech manufacturing grows, certain regions are likely to struggle to keep their home-grown talent and also attract experienced workers, Ning added, saying: “There is [already] a shortage of technicians, skilled workers and new-type talents in some companies in the coastal areas and in central and western China.”

This final instalment in the series will look at the situation in China’s traditional industrial base of Chongqing.