Is China’s concern over a possible US dollar shortage risk forcing companies to sell overseas assets?

- China’s need for US dollars to repay debts, pay for imports and fund Belt and Road initiative projects may exceed its US$3.1 trillion in foreign exchange reserves

- Anbang Insurance Group, Dalian Wanda Group and HNA Group have all been pressured to sell assets amid the trade war with the United States

This is the final article in a three-part series looking at China’s US dollar shortage risks in the trade war, as it aims to open up its markets.

Anbang Insurance Group’s plan to sell its condos at the Waldorf Astoria hotel in New York is the latest in the string of high-profile Chinese divestments that underscores China’s concern that the nation is running short of US dollars.

The Chinese holding company bought the Waldorf for a record US$1.95 billion in 2014, but under pressure from the Chinese government, is reported to be seeking buyers for the 375 flats at the hotel despite a glut of unsold luxury flats in Manhattan. In total, it is aiming to shed a portfolio of assets that includes 15 hotels having, like other highly leveraged Chinese conglomerates with overseas investments, been placed under scrutiny by Beijing.

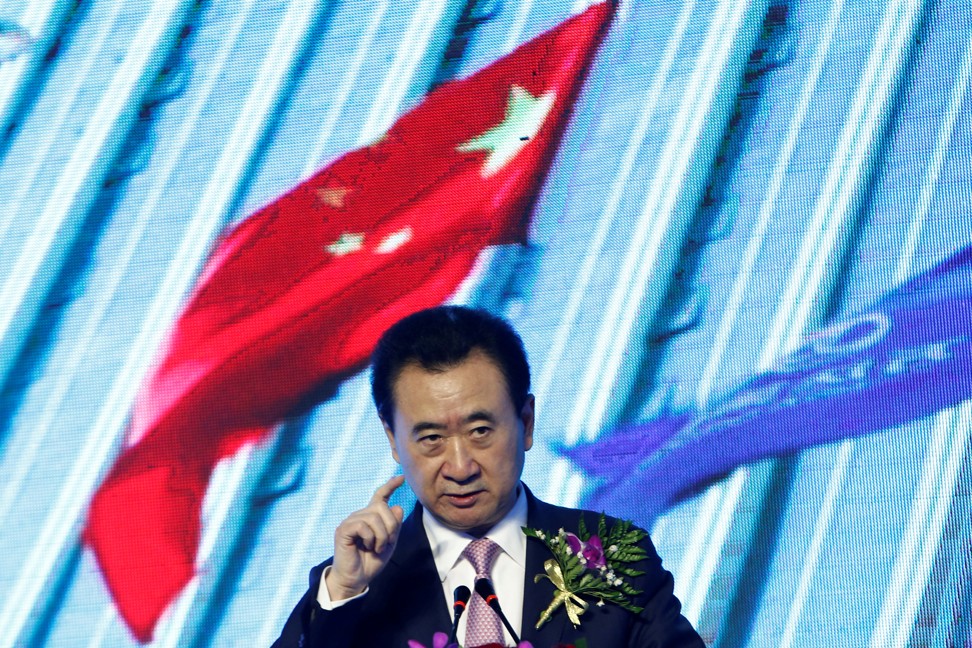

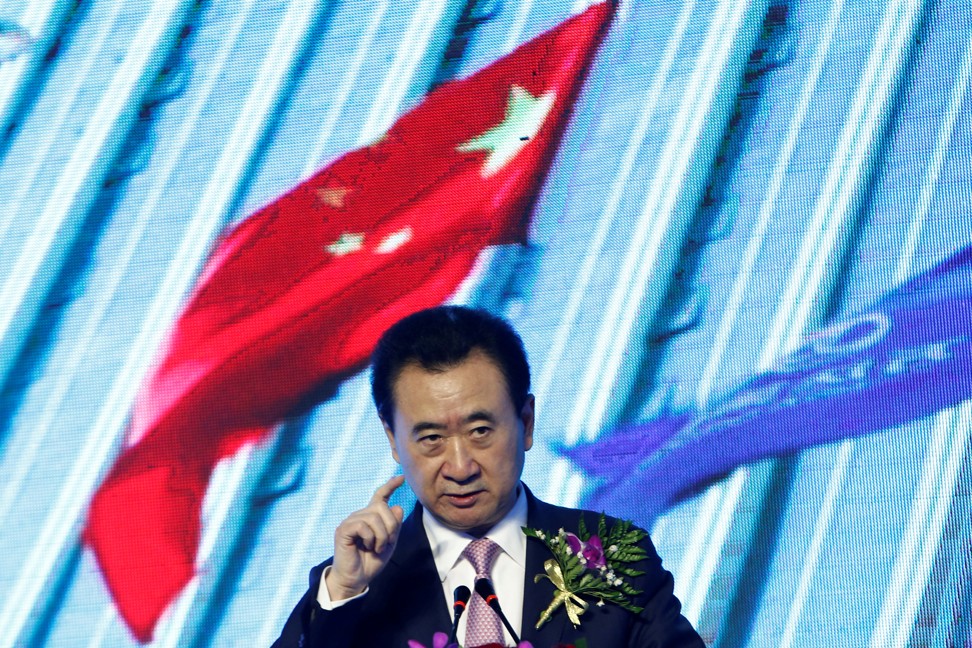

Chinese real estate mogul Wang Jianlin’s Dalian Wanda Group has dumped US$25 billion in assets since 2017, while troubled conglomerate HNA Group was forced to sell everything from Hong Kong land parcels, to its stakes in Deutsche Bank, Hilton Grand Vacations as well as its airlines. Chinese oil giant CEFC China Energy also wants to sell 100 properties worldwide.

The government’s dramatic about-face from encouraging aggressive overseas acquisitions to cracking down on risky lending and overseas transfers underscores worries over the risk that the nation could run short of enough US dollars to make the interest and principal payments on its mounting debt at a time when the current account balance is coming under pressure.

“These companies are selling their assets because they don’t have enough US dollars,” said Kevin Lai, chief economist for Asia excluding Japan at Daiwa Capital Markets. “China does not want to use its US$3 trillion foreign reserves for the debt repayments, so that is why these companies need to sell their assets.”

But with state-owned banks having lent heavily to these trouble groups, China’s policymakers will not allow the conglomerates go bankrupt, meaning an increasing demand for US dollars is needed to support inefficient, cash strapped companies, complicating China’s risk of a US dollar shortage. China also has the same need to its Belt and Road Initiative.

On the surface, China should be the last country to worry about a US dollar shortage given that its US$3.1 trillion worth of foreign exchange reserves is the largest help by any nation.

China does not want to use its US$3 trillion foreign reserves for the debt repayments, so that is why these companies need to sell their assets

But analysts believe China’s reserves may be insufficient to pay for its massive imports and debt payments in response to a worse-case scenario caused by the ongoing trade war with the United States, particularly since many of its assets cannot readily be turned into cash to help the central bank to save a crashing financial system or sharp devaluation of the yuan’s exchange rate.

“In reality, they don’t have as much as US$3.1 trillion of liquid reserves,” said Rabobank analyst Michael Every. “I would estimate they probably only have a little bit more liquid reserves than what they hold in US Treasuries.”

US Treasury data shows that US$1.1 trillion of China’s reserves are invested in US government bonds, with more than US$200 billion invested in US agency debt and US$280 billion in US corporate stocks, although as with most nations, it is hard to obtain an exact picture of the composition of China’s US$3.1 billion in foreign exchange reserves.

The remaining reserves may be invested in illiquid assets, including initial capital for the China Investment Corporation, the nation’s sovereign wealth fund, the Silk Road Fund that invests in the Belt and Road initiative infrastructure projects and cash-for-commodities loans to countries like Venezuela.

Reflecting the government’s increasing caution in managing the nation’s reserves, one of many investment arms of China’s State Administration of Foreign Exchange (Safe), Gingko Tree Investment, decided to sell the landmark Ropemaker Place office block in London in 2018 after having built up a portfolio of the most expensive properties in the United Kingdom, Belgium, Austria and Germany.

It is no secret that China is suffering huge losses in many of its investments that are funded in US dollar and Hong Kong dollar-denominated borrowings in the international markets, which are likely to keep expanding each year.

“Offshore demand for US dollar debt and bank borrowings from these people is strong,” said Lai from Daiwa Capital Markets. “China needs them to keep borrowing US dollars, with most of the funds converted into yuan to create fresh capital inflows and prop up the currency’s exchange rate.”

The root of the US dollar shortage issue goes back to the priority China places on maintaining stability and supporting its political objectives over maximising returns on its investments, with projects often failing to generate sufficient returns to make the accompanying debt burden worthwhile, analysts said. This means a continuous demand for US dollar-denominated lending from Chinese state banks by inefficient, cash-strapped companies and loss-making projects, is unlikely to stop.

“In China, there are capital controls and a desire from the central government to not show any financial distress. But this is happening at the cost of keeping many weak companies alive,” said Daniel Tabbush, founder of Asian bank consultancy firm Tabbush Report. “Most countries, foreign bankers and investors feel a more efficient allocation of capital, and a more open economy would be more ideal.”

Safe data shows China’s external debt rose 12 per cent year-on-year to US$1.97 trillion in 2018, due largely to increasing US dollar borrowing by Chinese companies. Similarly, the exposure of banks combined with the outstanding supply of bonds issued by Chinese joint-ventures, state-owned enterprises and mainland private companies in Hong Kong reached a record high of HK$4.4 trillion (US$562 billion) in the first quarter of 2019, according to data from the Hong Kong Monetary Authority.

Safe created a co-financing office in 2013 to facilitate Beijing’s strategic goal of securing energy and raw material supplies, with its main job providing US dollars to financial institutions, such as the official China Development Bank, to lend.

President’s Xi Jinping’s signature Belt and Road initiative to promote infrastructure development to link Asia, Europe, Africa with China, is being largely financed in US dollars, adding to worries of a shortage. Beijing, though, would like to promote the usage of the yuan for its Belt and Road initiative projects for the purchases of oil or raw materials, or for debt repayments, reducing its reliance on US dollars.

But China’s stringent capital controls has made conversion of the yuan increasingly difficult and the internationalisation of its currency has expanded only slowly.

“There isn’t an official breakdown of the currencies used for [Belt and Road initiative] projects but they are very likely to be dominated by US dollar denominated financing,” said Nathan Chow, an economist at DBS Group Research.

A total of US$614 billion has been invested by China in Belt and Road initiative projects, with another US$5 trillion of funding projected to be required by 2038, according to Veasna Kong, an economist at Moody’s Analytics.

But China and other participating countries are becoming wary over whether these projects can succeed commercially after new Belt and Road initiative construction contracts slumped to around US$63 billion last year from a peak of US$97 billion in 2016.

“Compounded by China’s reluctance for transparency about the projects, there are real doubts on the efficiency and effectiveness of the projects,” Kong added.

Most respondents in a survey by international consultant KPMG said that it was difficult to raise project financing for Belt and Road initiative projects on acceptable terms, manage financial risks and achieve profitable returns because of related high risks, institutional constraints as well as capability limitations faced by participants.