01:30

Workers unhappy about China’s plan to change decades-old retirement age rules

This is the first in a series of stories about China’s once-a-decade census conducted in 2020. The world’s most populous nation will release the national demographic data on Tuesday, and the figures will have far-reaching social policy and economic implications.

This story was originally published on April 28, 2021, but it has been republished and updated after the National Bureau of Statistics announced the release date.

Data from China’s latest nationwide census is expected to show a critical downward shift in the nation’s population trajectory, analysts said, making decisive reforms in population planning an urgent task for policymakers.

The census results will show China’s population continued to grow over the last decade, the National Bureau of Statistics announced last week, refuting a news report that it would show an outright decline.

However, demographers say the start of China’s population decline is likely to begin in the next few years.

The once-a-decade census, gauging changes in the size and diversity of China’s population, is an essential tool for future government policies. Beijing is currently in the process of implementing its new five-year plan that will set economic and social targets for the 2021-25 period, and census data will play a big part in the upcoming policy debate.

In particular, the outcome of the census will cast the spotlight on long-standing questions about the need to end limits on the number of children a family can have, to lift the retirement age, and to abolish the decades-old hukou registration system, which restricts the mobility of Chinese workers, straining overall economic growth.

China conducted its seventh population census in November and December last year, gathering a wide range of personal and household information pertaining to age, education, occupation, migration and marital status.

Based on the previous census in 2010, the upcoming initial release of 2020 census data is likely to contain details regarding gender composition; population breakdowns by age, nationality, and education level; and population figures from each of China’s 31 provincial-level jurisdictions. More detailed data will come out later this year.

It is unclear whether the initial figures released by the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) will include new birth data – the most consequential figure in the report – covering the census period from November 1, 2019, to October 31, 2020, because preliminary data released in 2010 did not include those figures. The NBS said this month that it might reveal more data this time.

Analysts widely expect the new census data to show an overall decline in China’s population due to a falling birth rate, warning that this is one of the largest risks facing the outlook for the world’s second-largest economy.

The last time China’s population dropped was in 1960-61 due to the impact of the Great Chinese Famine. The population fell about 10 million in 1960 and a further 3.4 million in 1961 before rebounding by 14.4 million in 1962, according to official figures.

In an unusual move, the country’s central bank earlier this month called for the immediate liberalisation of China’s birth policies, warning that the nation faces the risk of having a smaller share of workers supporting a higher burden for elderly care than the United States by 2050.

Four researchers from the People’s Bank of China said the country should not interfere with people’s ability to have children, or it will soon be too late to reverse the economic impact of a declining population. In 2016, the government abandoned its one-child policy – in place since the late 1970s – and allowed Chinese couples to have two children.

Beijing had expected a surge in births after embracing a two-child policy, but after decades of economic growth and tight birth controls, and given the high cost of raising a child in Chinese cities, the population has proven more reluctant to take advantage of the change than the government had anticipated.

Yu Luming, deputy director of Beijing’s working committee for the elderly population, said in an interview with state media in March that the speed and scale of population ageing in China were “unprecedented”.

“The first thing is to study and introduce a pilot programme to liberalise family planning as soon as possible,” Yu said. “The second is to implement a series of supporting policies to boost births as soon as possible.”

Over the past four decades, critics have charged that Beijing’s family-planning policy has been too conservative.

Zhai Zhenwu, chairman of the standing council of the China Population Association under the National Health and Family Planning Commission, told Shanghai-based Jiemian media in December that individuals should be able to decide how many children they have.

His comments signal an attitude shift about family planning among policymakers, given that Zhai expressed opposition to implement a “two-child” policy.

There are already signs that China’s birth rate and population are falling, with some experts warning of grave consequences. The nation’s capital, Beijing, which has a population of around 21 million, suffered a 24.3 per cent decline in its birth rate in 2020 compared with a year earlier, according to data released this month from Beijing Municipal Health Commission Information Centre. The total number of births in Beijing in 2020 was 100,368 – a decline of 32,266 compared with 2019’s 132,634, and the lowest figure in a decade.

According to an estimate by the China Population and Development Research Centre, a think tank under the central government, the nation’s population could peak around 2027 – the year when India may overtake China as the most populous country in the world – and fall to around 1.32 billion by 2050.

Over the past five years, the number of Chinese women in the prime childbearing ages between 20 and 34 has been falling steadily at an annual rate of 3.4 million. This pace of decline will almost double to 6.2 million in the next five years, according to the centre.

Consequently, the country’s annual number of births will fall to around 11 million by 2025 if China manages to keep its fertility rate at 1.5 births per woman, which is considered low. In comparison, Japan’s fertility rate was 1.369 in 2020.

James Liang, a research professor of applied economics at Peking University’s Guanghua School of Management, said in a blog post in December that the change in Zhai’s attitude could be interpreted as a sign that the end of birth restrictions in China was approaching.

“However, Zhai Zhenwu does not seem to realise the urgency of fully liberalising and encouraging childbearing,” Liang said. “We believe that the liberalisation of family planning has little effect on raising the birth rate, but this does not mean that it should not be implemented as soon as possible. Not only should it be implemented as soon as possible, but having children needs to be strongly encouraged.”

Ren Zeping, chief economist with Evergrande Group, predicted earlier this year that China’s population would contract during the 14th five-year plan period, and would begin to shrink sharply starting in 2050. By 2100, China’s population will drop to fewer than 800 million people from just under 1.4 billion in 2019, according to Ren’s estimates.

“The ageing population and declining birth rate are among the largest grey rhinos in China. Due to the long-term implementation of the family-planning policy, China’s population crisis is approaching, and the economic and social problems brought about by it will become increasingly severe,” Ren said in a research note in January.

In addition to its impact on birth-control policies, the census data also looks to factor in ongoing debates of hot-button issues, including the age at which individuals can retire, as well as an overhaul of the hukou system that could give people from rural areas more opportunities to become permanent residents in larger cities – a move that would speed up urbanisation. This would improve the income of workers and allow them to better support the social security system.

China’s hukou system is based on the birthplace of a person’s parents. Without official urban residency, many migrant workers have no access to social welfare benefits or government services, from pensions to public education. Many migrants working in cities have left their families behind in their hometowns and must return there for medical care.

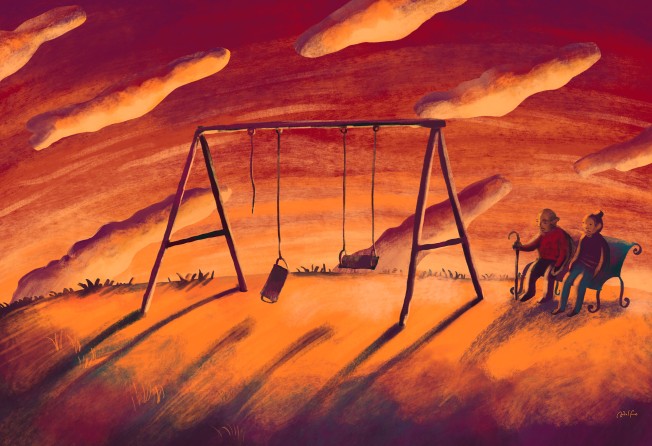

And for more than four decades, China’s retirement age has remained unchanged at 60 for men and 55 for women, though it can be even earlier for women in blue-collar jobs. As life expectancy increases, so does the economic burden of elderly care, but the nation’s workforce paying for those costs is already shrinking. The central government announced in March that it would gradually increase retirement ages, but there remains strong opposition in many quarters to the idea.

In the midst of the policy debate generated by the census figures, there are also lingering questions about the accuracy of China’s official data. In previous years, there has been a large gap between official data and academic estimates based on censuses.

Yi Fuxian, a researcher at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, said last year that China had “seriously overestimated the country’s actual birth rate and population size” in its official 2019 demographic data.

Yi estimated that China’s actual population size was 1.279 billion at the end of 2019, or 121 million fewer than the officially stated total of 1.4 billion. The actual number of births in China in 2019 should have been about 10 million, instead of 14.65 million reported by the NBS, Yi said.

“The wrong demographic data has not only delayed the adjustment of population policies, but also misled other policies,” Yi explained. “The statistics bureau needs to keep demographic data consistent with the past, or officials will be held accountable.

“The quality of the 2020 census may well be worrying.”