Why Hong Kong's remarkably diverse marine ecosystem is in peril

People who have lived in Hong Kong for some time know it is full of surprises. For conservationists currently marking the city's inaugural Ocean Appreciation Month, the occasion for a stocktake shows how special our surrounding marine environment is. But these qualities are a cause for concern as much as celebration, and may hold salutary lessons for the world.

What is so special?

Keen divers often rave about the kaleidoscope of marine life seen around reefs in Southeast Asia or the Maldives. Yet the species per unit area in Hong Kong waters is "at least a hundred times higher than many other regions in the world", according to a joint report by the Swire Institute of Marine Science (Swims) and the University of Hong Kong's School of Biological Sciences.

Titled "A review of marine biodiversity and ecological surveys in Hong Kong", the 2014 study found that our seas are home to more than 5,600 species of marine life.

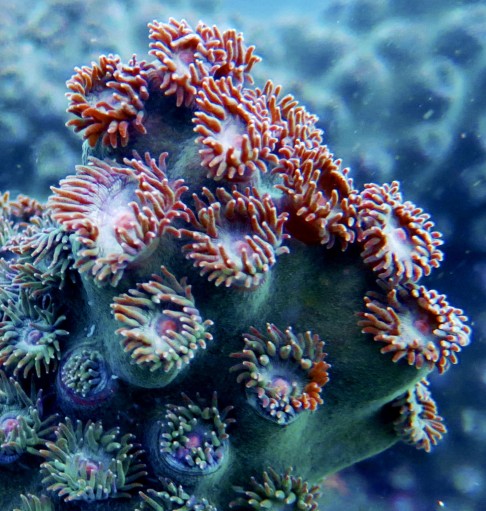

In fact, although Hong Kong waters cover about 1,600 sq km, they boast 84 species of hard coral - more than all of the Caribbean, which covers an expanse of 2.75 million sq km, says David Baker, a coral expert and an assistant professor at the university.

Several factors account for this wealth of species, mainly related to Hong Kong's position.

"The diversity of life you find here is because we're sitting on the edge of two worlds: we have a seasonal shift from a temperate marine ecosystem to a tropical ecosystem every year, so that variability increases the attractiveness of Hong Kong to a wider variety of species," Baker says.

Seasonally, the diversity is changing all the time. As a result, we find coral coexisting with mussels and sponges, which is very uncommon, he adds. And being situated near the Pearl River Delta means Hong Kong enjoys the added mix of its estuarine ecosystem.

But the factors that are contributing to a crisis in oceans all over the world are also evident in Hong Kong and, in some instances, magnified. Its incessant cycle of building brings a constant flow of muck that washes to the seabed. Reclamation works - including the planned third runway at Chek Lap Kok airport - add to the pollution in local waters.

Hats off

One bright spot amid all the filth is the government's harbour area treatment scheme (Hats). Stage one of the scheme provides basic filtration to 75 per cent of sewage from urban areas around Victoria Harbour and pumps it via a deep tunnel to a Stonecutters Island facility for enhanced treatment.

"Hong Kong is quite good in terms of water quality management in the region," says Professor Kenneth Leung Mei-yee, associate dean of science at Hong Kong University.

With 75 per cent of the discharge from the city collected daily, "that's 1,700 Olympic swimming pools, 2.5 million metric tonnes of waste a day".

"We've made significant progress in the past 20 years," Leung adds.

Stage 2A, which will be rolled out later this year, will expand filtration works to cover the remaining 25 per cent of the waste.

But conservationists and scientists worry that stage 2B, which sends this waste water on Stonecutters Island for biological treatment, has been put on hold.

Biological treatment is the "only way to remove most of the organic material and reduce pathogens", Leung says.

It suggested that funds would be better spent encouraging mainland authorities to clean up the delta.

Environmental groups and experts such as Leung reject this notion. Following that line of reasoning, he could teach his daughter that if she made a mess, she would not have to clean it up if her classmate made an even bigger mess. "I don't accept that. It's not logical," Leung says.

Net gains

A government ban on trawling, which came into effect in 2012, has been widely lauded as a breakthrough for restoring devastated fish stock, with the WWF-Hong Kong calling the move a "giant first step to save our near-collapsed marine ecosystem". The destructive practice of using weighted dragnets to scoop up everything from the seabed has led to dwindling catches while damaging coral reef and other fish habitats. Once a common food fish, the mud grouper is now an endangered species, as is the yellow croaker.

Anecdotal reports suggest that fish populations are beginning to recover, says Yvonne Sadovy, a professor of biological sciences at the University of Hong Kong.

"Enforcement is a big problem," she says. "There are problems with illegal fishing from Hong Kong, mainland and other vessels."

Despite talk about introducing barriers and underwater obstacles to trawlers, there has yet to be any concrete action. Moreover, the ban applies to just one type of fishing: "After the trawling ban, quite a few people have reported increased gill net fishing," Sadovy says. "If you use gill net fishing as a replacement for the trawling you're not going to get a lot of the benefits."

(Such nets hang vertically in the water like a mesh fence, stretched out between a float line at the top and a lead line at the bottom.)

Man-made reefs

The Agriculture Fisheries, and Conservation Department has been creating man-made reefs in surrounding waters since 1996 using material such as old car tyres and concrete blocks. The idea is that they provide surfaces where barnacles, oysters and coral can attach and grow, building a habitat that can provide food and shelter for fish.

But the initiatives aren't always successful and organisations such as the Ocean Conservancy argue the process of building artificial reefs can damage habitats and displace naturally occurring species.

A study of artificial reefs in Southeast Asia by Swims and the department of ecology and biodiversity at HKU found no scientific evidence that they improve fisheries.

"Indeed, with the exception of well-researched examples, such as shelters for juvenile lobsters in the Caribbean, artificial reefs are nowhere clearly demonstrated to enhance populations of exploited species," Sadovy says.

"Artificial reefs should still be considered an experimental approach in fisheries management, subject to evaluation."

Lessons for the world?

With the city's extensive reclamation projects, construction, depleting fish stock and coastal waters tainted by domestic waste and pollutants from the Pearl River Delta, the seas around Hong Kong can present a grim picture. Yet, it is also a microcosm that can hold clues to managing marine habitats around the world.

"This can be very important because as coral reefs are being lost all over the world, scientists are looking for examples of resilience to human stressors," Baker says. "So we can consider Hong Kong as a sort of biological repository for unique genetic strains of corals that may be very critical as global [climate] change continues."

Baker cites a type of massive coral, called Porites. Describing them as the "redwoods" of Hong Kong's underwater world, he says there are Porites colonies in Hong Kong that are about 200 years old.

"They were here when the British established the colony. There is something about these species that allow them to survive."

Then there are the brain-like Platygyra corals with polyps that can puff up in a way that shakes off sediment. "This ability allows [Platygyra] to live in areas where other corals wouldn't be happy."

We need effective legislation, political will and public support to maintain our marine ecosystem and the benefits and enjoyment we can gain from it

Still, there is a limit to how such traits can cushion the species against a deteriorating environment. "Platygyra used to be there in higher abundance but now are harder to find thanks to development in the Pearl River," he says.

But until the seas are cleaner, can transplanting hardier corals help build a habitat more conducive for marine life? Scientists have explored the notion, termed assisted migration, as a last-ditch measure. "With corals there are issues of international trade so it's not as simple as just shipping them. We also have to be mindful of genetic diversity," Baker says. "There may be a reason to pursue it in the future. For example, imagine a post-apocalyptic scenario in which coral is wiped out; then we may use assisted migration. But that's an extreme case."

Meanwhile, local scientists have been collaborating with government environment and fisheries officials on plans to improve the state of Hong Kong's marine ecosystem.

"I hope we can create a relationship because those two parties are vital for making our oceans healthy," Baker says.

They also hope to draw on the latest findings presented by experts at an upcoming international conference on marine ecosystems.

Sadovy says: "Fisheries need to be managed or we risk losing species and income-generating opportunities, and we become increasingly dependent on imports from other countries and a burden on their fisheries.

"We need effective legislation, political will and public support to maintain our marine ecosystem and the benefits and enjoyment we can gain from it."