5 of the most enduring myths about video games answered

From Pong to Pac-Man, from Death Race to Angry Birds, we put to rest some myths about origins, violence and sex discrimination, some of which have been doing the rounds since the 1970s

For decades, video games have mystified people who don’t play them. The New York Times Magazine grappled in 1974 with the emergence of the arcade game – calling it “the space-age pinball machine” - in Manhattan bars. What was this new coin-operated amusement? If not a kind of pinball, was it some sort of newfangled jukebox? Electronic foosball? How much money was it making? Was it addictive? Could it help sick people? Train air-traffic controllers? More than 40 years later, many of these questions are still with us. And some myths remain extremely difficult to dispel.

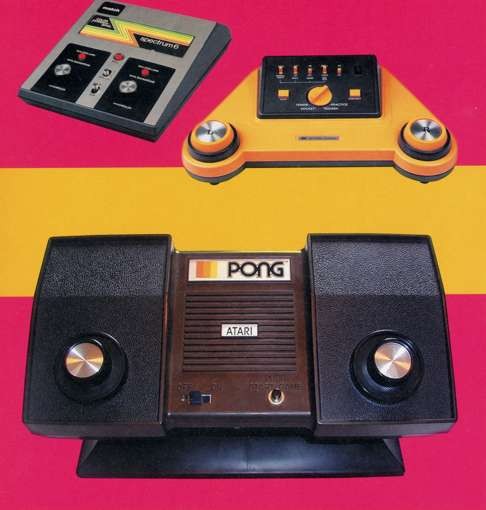

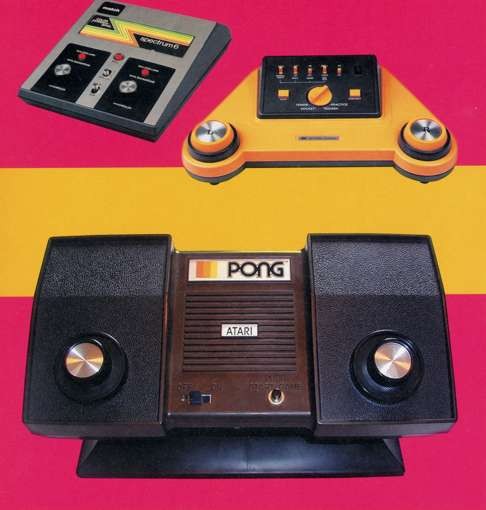

1. Pong was the first video game

Despite numerous debunkings, the idea that Pong was first persists. A headline in Vanity Fair illustrates this common misconception: The Origins of the First Arcade Video Game: Atari’s Pong.

Pong was a huge commercial success, one that helped turn a nascent medium into mass entertainment. But it wasn’t the first arcade game, nor was it the first home video game that you could hook up to your TV. Pong wasn’t even the first video game version of table tennis – it was just the first one that asked you for a quarter to play it.

Like any medium, video games have many antecedents. Most experts point to William Higinbotham’s Tennis for Two, a demonstration created for an open house at Long Island’s Brookhaven National Laboratory in 1958, as the first true video game.

The first home game console was not Pong but Baer’s Magnavox Odyssey, which went on sale in 1972, three years before Atari’s home version of Pong. It had table tennis in it, too.

Pong was not even the first coin-operated arcade game from Atari founder Nolan Bushnell. That distinction goes to 1971’s Computer Space.

2. Video games are bigger than films

Since the early 1980s, people have speculated that the popularity of interactive entertainment was hurting ticket sales at cinemas. In 1982, the New York Times reported that video games grossed US$8 billion a year, “compared with about US$3 billion for all the movies shown in cinemas.” More striking, the paper reported that Pac-Man had “grossed about US$1.2 billion – three times as much as Star Wars, history’s most popular film, has earned in the five years since its initial release.” The claim that the size of the video game industry rivals or exceeds Hollywood has been a staple of mainstream news reporting for more than three decades.

It’s true that Americans spent almost US$24 billion on video games last year, compared with a measly US$11 billion on movie tickets. But the box office is not even close to the entire revenue stream. Americans spent an additional US$18 billion on home entertainment including Blu-rays, DVDs, iTunes and Netflix.

Sure, some of that money is spent to binge-watch television shows instead of films. But that is already US$5 billion ahead of video-game revenue without considering the cost of (or the rights fees paid by) premium cable channels such as HBO.

The video-game numbers are inflated, too, by the inclusion of sales of hardware, such as consoles and controllers. The home entertainment figures don’t include the cost of things like Blu-ray players or universal remotes.

More important, dollars aren’t people. Here’s some rough maths: when Grand Theft Auto V makes US$1 billion, it’s because 20 million people, give or take, have bought the game. When The Force Awakens makes US$1 billion, it’s because 100 million tickets were sold, more or less. Even if every ticket buyer saw the new Star Wars film twice, and every Grand Theft Auto V player shared the game with another member of their household, the Lucas film would still come out ahead.

3. They’re for men

According to a Pew Research Centre survey published in December, 60 per cent of Americans believe that “most people who play video games are men.” Top-selling games such as Call of Duty and Madden NFL tend to be marketed to men, and almost three times as many men describe themselves as “gamers” (15 per cent of men compared with 6 per cent of women).

The latest data from the Entertainment Software Association, the lobbying arm of the video game industry, does indicate that the majority of players – 60 per cent – are men. But that still leaves a sizable percentage of female players. There are also more women over 18 who play video games than boys under 18 who play; women aged 50 and older are more likely than their male counterparts to play. A Pew Research Centre survey published last August found that nearly 60 per cent of teenage girls play video games on a computer, console or mobile phone.

One reason these players aren’t noticed: almost half of these teenage girls never play online games, and a quarter of them always play alone, never in the physical presence of another person. Only 28 per cent of the girls who play video games online use voice chat to talk to other plays. (More than 70 per cent of teenage boys who play online talk.)

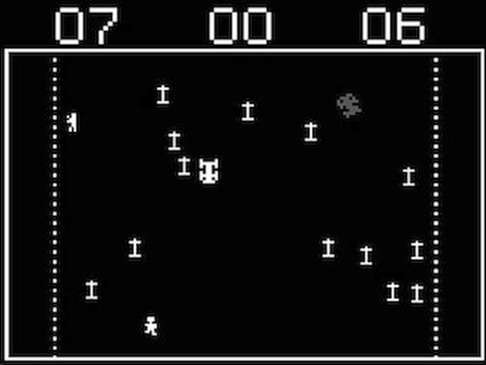

4. Violent video games are a cause of real-world violence

In the wake of the 1999 massacre at Columbine High School, video games were blamed for helping to numb the shooters to the consequences of their actions. Yet these allegations are much older than the age of mass violence: in the 1970s, journalists fretted about an arcade game called Death Race, and in 1982, The MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour hosted a debate on PBS over whether games like Space Invaders were too violent and taught children not to respect the value of human (not merely alien) life.

These concerns aren’t baseless. A review of the scientific literature, conducted by an American Psychological Association task force, found a “well established” link between violent video games and short-term increases in aggression. People who play violent games in laboratory settings are willing to administer, say, more hot sauce to a stranger, or a louder blast of noise, than people who don’t play violent games.

Playing violent games also leads to higher levels of what psychologists call “aggressive cognition” - for example, completing a word with a missing letter by choosing a D for “explode” rather than an R for “explore.”

But many scholars dispute these findings, saying that at best they indicate an effect on thoughts rather than actions, and at worst merely prove that looking at an image of an explosion makes you think about explosions. Many video games, including Pac-Man, could be called “violent” under the vague definitions psychologists often use. Frustration or competition, rather than violent imagery, might be leading to the heightened feelings of aggression, these researchers say.

Hundreds of scholars signed an open letter in 2013, when the task force began its work, to protest that media-effects research has well-known methodological issues and that “responsible scholars” may conclude that violent media does not increase aggression. Youth violence is at a historic low, the letter pointed out, at the very same time that violent video games are more popular than ever.

Regardless, the task force did not find evidence that playing violent video games leads to criminal violence or delinquency. And the favourite game of Adam Lanza, the Sandy Hook killer, was the non-violent Dance Dance Revolution.

At least since Steven Johnson’s Everything Bad Is Good for You was published in 2005, players have proudly declared that their hobby may look childish and brutish, but it’s actually changing their brains for the better.

5. They’re making us smarter

And they might not be wrong. “Action games” – mostly first-person shooters – have been found in a number of studies to improve hand-eye coordination and spatial thinking. More surprising, these games can improve vision, increase attention and make players more efficient at mental task-switching, even when they’re not playing the games.

But only some video games have these effects. Playing chess – whether on a physical board or a screen – doesn’t confer any of these benefits. Nor does playing some of the most popular video games, including the slower-paced Candy Crush Saga, Angry Birds, the Sims, Minecraft or even Tetris. Some sports, driving and adventure games might be considered “action games,” but the research has emphasised the benefits of shooters, which are more perceptually demanding. And the games that improve cognitive performance tend to be the very ones that the American Psychological Association task force says increase aggression.

If you want the “superior cognitive abilities” that gamers were found to possess in a review of the literature conducted by Gillian Dale and C. Shawn Green, and published in the recent book The Video Game Debate, you’ll need to play an action game. Try Overwatch or the new Doom. You’ll probably improve your “perception, attention, memory, and executive functioning,” Dale and Green write. Just don’t handle the china after.

The Washington Post

Suellentrop is a host of the podcast Shall We Play a Game?