Why fear is the biggest obstacle to a future of driverless cars, and the scientists working to convince us of their possibilities

A car that’s also a gym, a hotel room, an office, a nanny to your kids? Anything is possible, say researchers planning for a future of autonomous vehicles – but not until people and officialdom, in Hong Kong and other cities, accept them

When is a self-driving car not a car? When it’s a piece of gym equipment, or a mobile hotel room, perhaps. These are some of the offbeat ideas being dreamed up by participants of the GATEway Project, an £8 million (HK$82 million) research initiative focused on driverless vehicles funded by the British government and industry, which began a trial with prototype driverless pods in April.

Instead of having an accelerator pedal or steering wheel, the pods are fitted with three sensors and five cameras that read their surroundings as they chauffeur volunteers along a two-mile (3.2km) test route in the London borough of Greenwich.

The pods operate in much the same way as autonomous vehicles being developed by Google and about a dozen major carmakers. What the researchers are studying, however, is not the mechanics but the technical, legal and societal challenges they pose.

“We are looking at the acceptance, hopes and fears of driverless vehicles. The issue is every new technology is accompanied by a wave of discomfort from customers, passengers and users,” says Rama Gheerawo, the director of the Helen Hamlyn Centre for Design and vehicle design department at London’s Royal College of Art, which is part of the consortium.

On paper, the case for autonomous vehicles is strong. US government statistics have shown that 94 per cent of road accidents are the result of human error, making us the biggest threat to road safety. Besides improving road safety, algorithms could calculate and control how cars cross junctions, removing the need for traffic lights and cutting journey times. Rather than going in circles or waiting in lines for parking spaces, it’s envisaged that passengers could simply disembark at their destination, leaving their vehicles to automatically park themselves and return when summoned.

If you want to make something work, people will have to want to use it. You can’t enforce solutions that people don’t appreciate

Despite these benefits, human acceptance remains the biggest barrier in the implementation of the technology, Gheerawo says. A fatal accident in the US state of Florida involving a Tesla operating on autopilot mode received widespread attention in May last year. It raised suspicion of driverless vehicles, even after an investigation found no defects in the system and the driver was revealed to have ignored several safety warnings. In Hong Kong, the Transport Department has prohibited the use of self-drive features in Tesla cars.

“You can invent the best technology in the world, but if no one understands it, wants it, or they’re fearful of it, it’s dead,” says Gheerawo.

They fail, he says, to understand that “the thing with autonomy is it’s not taking anything away from human beings, except such things as repetitiveness, calculation ... certain things you don’t want to do”.

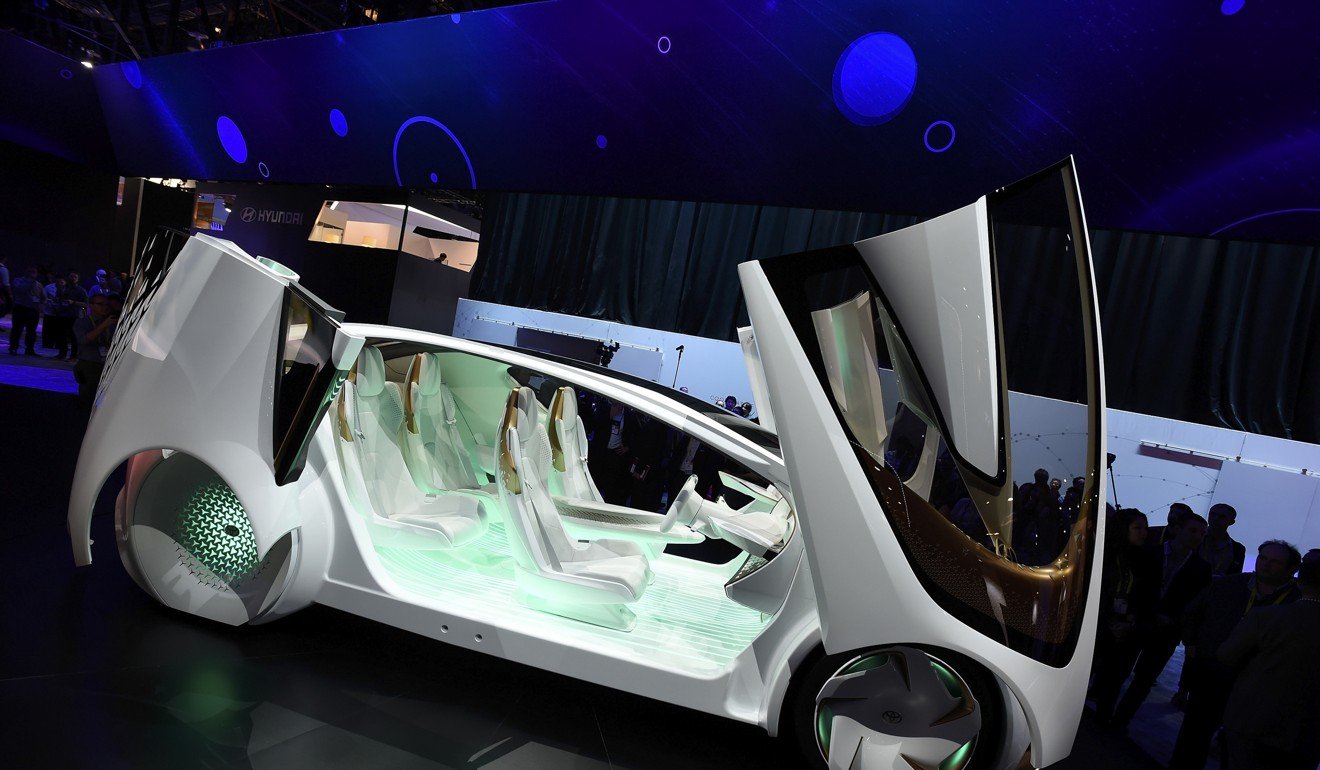

Autonomous vehicles could offer much more than just hands-free driving, and who is to say such a vehicle should have four wheels and look anything at all like today’s conventional vehicles? Believing so merely limits our imagination of what self-driving technology is capable of, Gheerawo says.

Coupled with advances in artificial intelligence and robotics, there are possibilities to dramatically transform the commuting experience, and even our lives.

For example, a car could be a moving container in which the occupant performs exercises that contribute to the energy needed to move the vehicle. Hotels may not necessarily need to be static buildings, but rooms on wheels, so a person can check in and go to bed in one city, and wake up in another.

“What if a car could be a nanny and pick your kids up from school? What if it could allow you to be more productive and relaxed, so the car was actually a living room and your commute to work was an extension of your home?” Gheerawo suggests.

You can invent the best technology in the world, but if no one understands it, wants it, or they’re fearful of it, it’s dead

Such ideas may seem too bizarre to be realised, but they do hint at the potential of the technology. And this is where design comes in, says Gheerawo, to reframe the problem and look at how the technology could be utilised for the benefit of people, especially those in need.

“I would hate to see autonomous vehicles as just playthings for the rich, or a kind of technology-driven circus act,” he says.

The GATEway Project is looking at how autonomous cars can improve the mobility of the disabled and the elderly, whose quality of life drops significantly when their driving licence is revoked, especially those living in car-dependent cities.

As the appearance and functionality of vehicles evolve, road systems will also be transformed, Gheerawo says. “At the moment, the road network and the idea of personal transport is seen as being quite environmentally unfriendly, but I think road vehicles shouldn’t be seen as the great enemy of the transport system,” he says.

Instead, the line between public and private transport will become increasingly blurred, he believes. In June US company Local Motors rolled out Olli, a 3D-printed, electric-powered driverless bus that is positioned as a “neighbourhood friendly mobility solution”. Rather than running on a fixed schedule and route, Olli, which is being tested on private property, can be summoned through a smartphone app. A similar project, the EZ10, is being tested in Singapore.

“We are just beginning to look at a driverless future and how you can have a seamless connection between different means of transportation,” says Onny Eikhaug, a programme leader at the Norwegian Centre for Design and Architecture. One proposal by Ruter, Norway’s public transportation provider, is a small fleet of driverless units that go door-to-door and help people travel the last kilometre home.

So how soon will it be before we see driverless cars on the roads? “It’s not a cliff-edge,” says Gheerawo. “In terms of technology, that’s short. That can be two years, max. If you’re looking at cultural acceptance, you are probably looking at another two years.”

Elon Musk, the CEO of electric car maker Tesla Motors, seems to agree. Musk has predicted that the company’s vehicles could feature level-five autonomy – meaning that the machines do everything – by 2019.

Most manufacturers are now in the final stage of conducting road tests. Yet it still seems to be overly optimistic to expect driverless cars to be commercially available by 2020 because of the non-technical complications they face – such as regulatory hurdles, liability and an insurance model.

But Gheerawo believes these obstacles can be overcome in about a decade, and insists the possibilities the future holds are endless.

“We want people to use our prototype. We want people to mess it up. We want people to dream and aspire,” he says, “because it’s a very basic prototype at the moment. But what it could be is anything.”