How digital streaming crowds out older movies and art-house films and threatens film and video history

Netflix and Amazon Prime offer large catalogues of popular films and TV series for subscribers to watch, but catering to the masses means old classics and art-house films are being ignored and movie buffs fear they may disappear

There isn’t much not to like about streaming video. Subscribe to Netflix or Amazon Prime, and you can choose from thousands of film and TV titles with the press of a button. No VHS tapes to get chewed up by a tape player, no DVDs to clutter the living room and collect dust and scratches. Whole seasons of TV series ready for binge viewing. This is entertainment technology at its best.

Or is it? Film historians and film buffs would beg to differ. For them, the rapidity with which streaming has supplanted discs and tapes as a viewing mode is a bug, not a feature. As the mass audience gravitates toward the big streaming services, those services have more incentive to focus their streaming inventory on recent and self-produced titles.

For classic film buffs, the golden age may have been the 1980s, when the rapid spread of VHS tape players awoke major studios to the commercial potential of marketing their back catalogues for home viewing. The trend continued through the DVD era – Warner Bros, Universal, and Disney were especially notable preservers and marketers of their archives – but it may be fading as physical discs fall out of favour.

There’s a sense of super abundance, but there are lots of important films that are not available

As the big streaming services increasingly define themselves as purveyors of mass market fare, the way that many film buffs first discovered the glories of cinema history – through serendipity – is evaporating. Several services have sprung up online to serve the classic film buff audience, but they have to be sought out by those with a pre-existing interest in the field – and they each require a separate subscription.

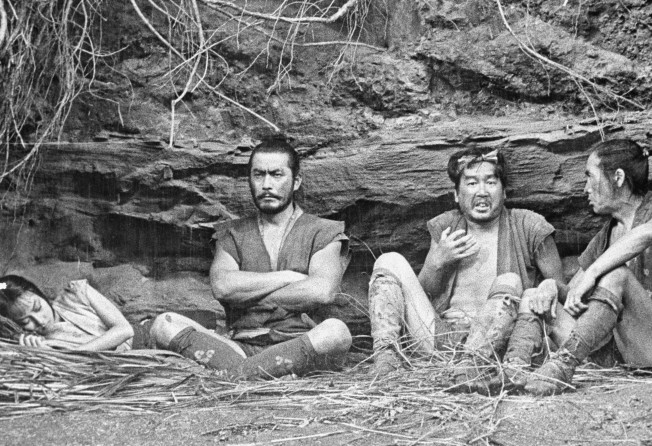

“Directors and screenwriters like Edgar Wright and Quentin Tarantino love to talk about the films that influenced them. But it’s very hard for people to see those films the way they did,” she says. Star Wars is having another moment, but how many people have seen The Hidden Fortress, the Akira Kurosawa film that was its inspiration?”

Concerns about the decline in physical distribution of film and video fall into two categories: technical and commercial.

Each technological transition seems to leave more history behind. Film historians say there were fewer classic films available on VHS tape than on 35mm and 16mm film, fewer still on DVD and an even smaller selection on Blu-ray discs.

At first glance it might seem that digital storage would be a more reliable and perhaps cheaper archival technology than film and magnetic tape – after all, what can go wrong with storing digital bits and bytes? Digital assets are subject to degradation from “heat, humidity, static electricity, and electromagnetic fields”, a 2007 Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences report warned.

They also have to be periodically migrated to new formats, because they can be illegible to new generations of read-and-write technology. (Nasa discovered this flaw in 1999, when it was unable to review data from the Viking spacecraft from 1975 because all the programmers familiar with the original format had retired or died.)

About 99 per cent of UCLA’s roughly 500,000 titles are archived on analogue media – 35mm or 16mm film or videotape – Horak says. Estimates for the creation of a digital asset management system are US$1.2 million and up, says Horak. “That is a huge expense for a public archive.”

The increasing focus of major streaming services on recent fare has left the field open for niche services.

Mubi, a 10-year-old, US$5.99 per month service that now claims 100,000 members, adds one film a day to its streaming inventory of foreign, independent, and art-house fare, and leaves it up for 30 days. Fandor (US$4.99 a month), a film buff site partially funded by the studio Lionsgate, offers an inventory of 5,000 streamed films with a focus on independent and foreign titles. The service says its speciality focus allows it to acquire films “the big players don’t think it’s worth investing in”, says Gail Gendler, Fandor’s head of programming.

The gold-standard classic-film channel for historians and film buffs is Turner Classic Movies, a cable channel that also operates the streaming service FilmStruck – which is now the exclusive streaming distributor for the Criterion Collection, the premier classic film library (from which one can stream The Hidden Fortress). A combined FilmStruck/Criterion subscription costs US$10.99 a month.

About 150 of TCM’s classic titles are available for streaming on FilmStruck, with plans to more than double that next year – in addition to the service’s independent, foreign, and Criterion offerings.

What worries film aficionados is that the rise of mass-market streaming will sap coming generations of their interest in classic films, which will in turn discourage those services and the studios themselves from continuing to invest in their century-old patrimony.

“Kids today are exposed to so much that they think that everything’s out there,” says Bordwell. “There’s a sense of super abundance, but there are lots of important films that are not available, including silent films that are impossible to see unless you go to a film archive and watch them on a flatbed moviola.”

Tabesh, for one, thinks it’s possible that digital storage and streaming will be the saviour of film history, not its nemesis.

“There are a lot of films that have never been available at all, even on DVD or home video, because there hasn’t been a market for them,” he says. “If anything, digital might make some of these more available to people. There are collectors of DVDs who will feel more safe owning the hard good. But over time, I think the convenience of digital will win out.”