Old feud stalls rebuilding of fire-ruined Chinese temple in Jakarta as flames of dispute still burn

Power struggle within foundation that manages the Dharma Bhakti temple means little progress has been made since a devastating 2015 fire, while the mixing of politics with religion threatens to further frustrate worshippers

Since a devastating fire tore through one of Indonesia’s oldest Chinese temples nearly three years ago, little progress has been made on restoring the centuries-old structure.

No one is certain when construction will begin. That is despite a groundbreaking ceremony that was supposed to kick off the process in July last year. What is known is that the main reason for the delay is a feud between two factions of the foundation in charge of managing the temple.

The wooden beams and columns of the Dharma Bhakti Chinese temple, in Jakarta’s Chinatown district of Glodok, were charred beyond repair as a result of the fire. Intricate carvings and ornaments are no longer recognisable. Tarpaulin sheets tied to flimsy bamboo poles stand in place of the missing roof tiles.

All parties involved agree that the structure must be completely demolished and rebuilt from scratch for safety reasons – and to rid the site of bad luck.

The Dharma Bhakti temple – also known by its Hokkien name Kim Tek Ie, or Jin De Yuan in Mandarin – is an important heritage site for the Chinese community in the Muslim-majority nation.

When the South China Morning Post visited recently, several workers came and went collecting floor tiles and sacks of cement littering the interior. But workers said the materials were for the temple complex’s courtyard, and not for renovating the historic structure itself.

Worshippers and neighbouring residents have theories about the slow renovation progress, ranging from bureaucratic red tape to the management’s inability to find contractors and artisans capable of restoring the building to its original condition.

Few may be aware that the problem stems from a bitter power struggle within the foundation that manages the Buddhist temple, which involves two key figures: the recently deceased Hindharto Budiman, who died last year and was the foundation’s chairman until August 2015, and Tan Adi Pranata, who took over.

The first temple on the site was built in 1650 as Chinese immigrants began arriving in the city, known as Batavia in Dutch colonial times.

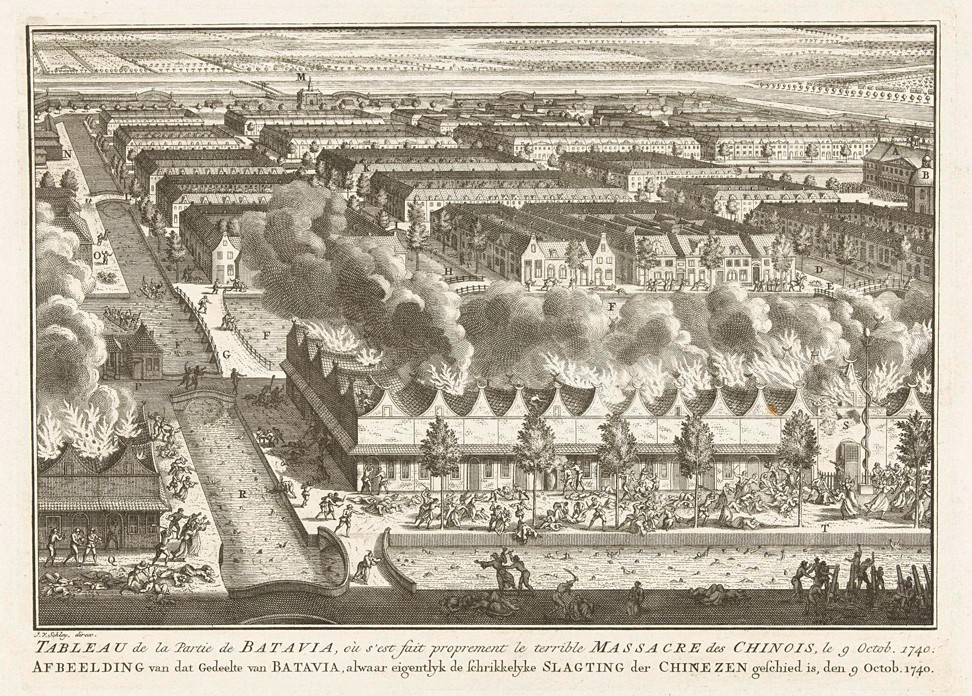

Along with almost all the houses and other buildings in its predominantly Chinese neighbourhood, the temple was burned down during a crackdown against a Chinese uprising in 1740. Historians estimate that as many as 10,000 ethnic Chinese were murdered during what became known as the Batavia massacre.

The temple was rebuilt in 1755 and its doors remained open to worshippers for 260 years until the early morning fire on March 2, 2015. A neighbourhood watchman, Hilman Sukirman, says he was at a nearby security post when the fire started.

“I heard a cry for help from the temple and I saw some people trying to rescue whatever relics and statues they could carry,” he says. “Before they could rescue more relics, the fire was already raging.”

An official inquiry ruled that the fire started when flames from lit candles burned a piece of tarpaulin sheet, which quickly spread throughout the temple.

Lighting candles for 15 consecutive days after the Lunar New Year is considered auspicious. Local residents blamed Budiman, then the temple foundation’s chairman, for leaving lit candles unattended at the temple.

“I wouldn’t have allowed it,” says Hartanto Wijaya, a caretaker at another historic temple in the area, Toa Se Bio. “When the temple closes, the candles must be extinguished. Who would tend to them at night?”

Eighty per cent of the centuries-old relics at the Dharma Bhakti temple were reduced to ashes, but the statue of Guan Yin, the Chinese Goddess of Mercy to whom the temple is dedicated, survived.

The temple complex was closed to the public after the fire, and months went by without any sign that it would ever open again, frustrating worshippers who flocked to the temple from every corner of the country.

Everyone is welcomed here, but we don’t like people mixing religion and politics

Linda Hartono says she travels 70km every week from Bogor, south of Jakarta, to pray before the Guan Yin statue, which has become even more revered since it emerged from the fire seemingly miraculously unscathed.

Glodok district is littered with temples and shrines, and some, like Toa Se Bio (dedicated to the Chinese wealth god Guan Yu), were built around the same time as Dharma Bhakti. But the Guan Yin at Dharma Bhakti “seems to be more potent”, Hartono says.

To the delight of many, the complex that houses the temple was reopened six months after the fire, this time under new management led by Tan Adi Pranata.

The Indonesian Ministry of Justice and Human Rights recognised Pranata’s claim for chairmanship of the Dharma Bhakti Foundation in August 2015 and he wasted no time in getting the site operational.

Pranata converted a storage wing at the complex into an area of prayer for Guan Yin. He tore down individual shrines at the back of the compound to make way for one large prayer hall, constructed out of steel frames and with corrugated metal roofs, and replaced all the burned statues and figurines.

The ousted Budiman, however, still regarded himself as the legitimate chairman of the foundation, and viewed Pranata’s move as an illegal and hostile takeover.

Budiman accused Pranata of trying to sell the compound. Pranata strongly denied the allegation.

“I am only doing this for the good of the worshippers. We have to serve the people coming to the temple to pray,” Pranata told the Post.

With the help of prominent lawyer and politician Yusril Ihza Mahendra, Budiman launched a legal case against the Justice Ministry, demanding that it rescind recognition of Pranata’s chairmanship. Budiman also convinced city officials not to meet Pranata’s management team until the case was resolved.

“For us, as long as they are not planning to alter or expand the original building, we have no problem issuing a permit for the renovation,” says Tinia Budiarti, head of the Jakarta Tourism and Culture Office, which oversees conservation of all historical buildings and sites in the Indonesian capital.

“Of course, we want to know whether they can find the same materials and hire architects with experience in restoring a historical building,” Budiarti adds. “But before that happens, we need them to settle their internal problems first.”

Without the temple’s legal documents – which are still in the possession of Budiman’s camp – Pranata cannot go ahead with the restoration. But that did not stop him from raising funds, and receiving donation pledges from powerful businessmen, politicians and several embassies.

Then, when no progress was seen after three lavish “groundbreaking ceremonies” over the span of two years and billions of rupiah collected, Pranata’s motives began to be questioned.

His decision to invite controversial politicians to the ceremony last July also did not sit well with critics. Guests included Jakarta Deputy Governor Sandiaga Uno, who was seen by activists and analysts to be taking advantage of divisive tactics and racial slurs directed at the city’s then governor Basuki “Ahok” Tjahaja Purnama, a Chinese Christian.

“Everyone is welcomed here, but we don’t like people mixing religion and politics,” one Glodok resident, who refuses to be identified, says. “We don’t like politicians at our temple.”

Glodok was one of the worst affected areas during a citywide riot targeting Chinese businesses in 1998, at the height of the Asian Financial Crisis that ended the 32-year presidency of dictator Suharto. Many feared a repeat of the same unrest in the lead up to February’s gubernatorial election.

Purnama lost his reelection bid after a series of massive rallies calling for his arrest in a blasphemy case. He was later jailed for two years for insulting Islam.

After a protracted court case, Indonesia’s Supreme Court has refused to issue a ruling on the dispute over the foundation’s chairmanship, says Mahendra, the Budiman camp’s lawyer, leaving the two sides in deadlock.

I don’t think the temple will be rebuilt any time soon. The dispute is too complex and both sides are not giving up without a fight

Some of the wealthiest Chinese-Indonesian tycoons have tried to act as mediators, Mahendra says. “We are dealing with really old people here. It is hard to reconcile them,” he adds.

Mediation attempts appeared to be bearing fruit in August, when both sides agreed to temporarily back down from their chairmanship claims. An interim management committee was installed, but then Budiman died in November.

Pranata refuses to say much about the dispute, fearing it might rock the ongoing truce between him and the late Budiman’s supporters.

He also refuses to speculate on the future of the mediation process now that Budiman has died, or whether the dispute will ever be settled. “We’ll see what happens next,” he says.

For worshippers, what matters is that they can still pray at the makeshift prayer halls.

“I don’t think the temple will be rebuilt any time soon,” says Wendy, one of the dozens of workers at the temple, while preparing incense sticks for visitors. “The dispute is too complex and both sides are not giving up without a fight.”