Chinese resettlement villages in Malaysia get a facelift, 60 years after the first ‘temporary’ settlements sprang up

- Built during the Malayan Emergency to separate Chinese from communist insurgents, ‘new villages’ today house 1.2 million people

- Community projects by artists, designers and architects are under way to revive and improve them

Look on a map and Kampung Cempaka new village appears indistinguishable from the rest of Petaling Jaya, a satellite city adjoining Malaysia’s capital, Kuala Lumpur. But Theresa Lim says she would never swap her “village” home for city life.

“We are probably the only new village in this part of Petaling Jaya,” says Lim. “If we don’t do anything, the original flavour of the village and the houses will be gone.

“We want to preserve its original features, including our Cantonese-Xinhui culture and food.” Most of Kampung Cempaka’s residents trace their roots to Xinhui in Guangdong province, southern China.

Lim is an enthusiastic supporter of projects designed to give new life to the urban village and preserve the memories of its older residents.

Kampung Cempaka is one of more than 600 so-called Chinese new villages across Malaysia – relocation settlements for Chinese on the Malay Peninsula initially built by the British colonial administration during the Malayan Emergency to cut them off from communist insurgents.

They were never meant to be anything other than temporary, but the settlements – called Xin Cun in Chinese and home to 1.2 million people – have become a fixture of Malaysia’s urban landscape. Now, 60 years after the first of these new villages was built, many are in decline. Younger residents have moved out, leaving an ageing population.

In recognition of their historical and cultural significance, a number of the new villages are being given a new lease of life by a team of artists, designers and architects tasked by the Malaysian government with carrying out community arts projects.

Curator Yeoh Lian Heng, who is leading the team, says the villages are historically and culturally unique, and should be preserved as part of Malaysia’s national heritage rather than being left to decay.

“The declining population and lack of job opportunities in the communities have weakened their cohesion and vibrancy. In addition to ageing and dwindling populations, new villages also face gradual encroachment from factories in surrounding areas,” says Yeoh, the founder of Kuala Lumpur’s Lostgens Contemporary Art Space.

Absorbing the new villages into cities is not a solution, Yeoh says. “Efforts to revitalise a community should not interfere with the original ecosystem or disrupt the daily lives of locals,” he says.

He hopes that community arts projects will make them more liveable, and thus encourage young people to return to their birthplaces. “Ideally, community work should be initiated by members of the community, with the help and cooperation of authorities,” he says.

“As artists and activists, we can help … the community document its history and culture. The villagers can discover the uniqueness of local culture and history as well as aesthetic values.”

New villages are saddled with a poor reputation, he says. “People tend to label the villagers uncouth or uneducated. They get a bad name. Many of the villagers themselves want to change these perceptions.”

Yeoh points out that since community work is in its infancy in Malaysia, there will be challenges – among them government policies, funding, and the lack of youth participation. In addition the public may not see the value in such an initiative.

Still, his team has made an encouraging start in Kampung Cempaka new village. Probably the newest new village in Peninsular Malaysia, it was established in 1969 when villagers were resettled there after a fire destroyed their homes elsewhere. It has just over 1,000 houses.

We would like to educate the villagers on how to do community work, so that they can be involved and be part of the restoration of their own village

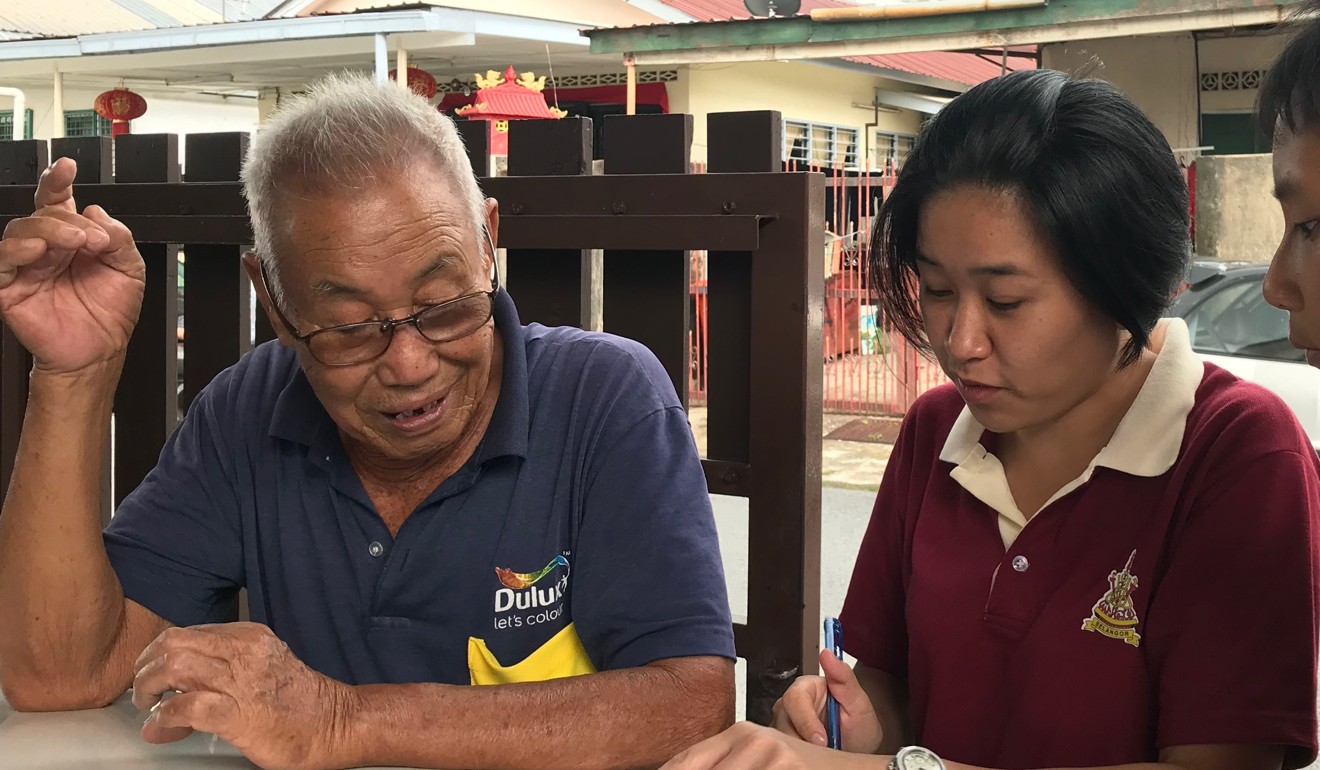

To begin with, Yeoh and his team conducted a door-to-door survey of homes and businesses with the help of villagers including Lim. “The questionnaires sought to find out basic information such as [the occupants’] family background, residents’ jobs and their needs. We also wanted to find out about the condition of their houses,” he says.

Yeoh and his team wanted to identify original wooden houses they could repair and repaint, but it turns out most of the original homes have been rebuilt.

From the survey, the team also found that some of the families had an interesting and important family history to tell. Some were keen to donate old family items to the community.

“One of our main projects is build a community museum. The museum would document how the village was established and tell personal stories. We are looking for intangible heritage to be preserved,” he says. The museum would open in three years’ time, he said.

Another project involves building a community space to address the village’s lack of public facilities. The team identified a plot of land by the river to develop into an outdoor public space. Yeoh says it could be used for the elderly to practise tai chi, children to play basketball, and for other purposes. Another plan is to beautify the nearby stagnant river and bring it back to life.

“We would like to educate the villagers on how to do community work, so that they can be involved and be part of the restoration of their own village,” he says.

The team also wants to create a map featuring places of interest in the village.

Before efforts to rejuvenate new villages can move forward, the Ministry of Housing and Local Government needs to make it easy for residents to apply for title to the land on which their homes and businesses sit.

Because many of the new villages were established before Malaysia gained independence in 1963, and weren’t meant to be permanent, regulations don’t cover the ownership of the land they were built on. Residents fear their land could be taken away from them at any time.

An official of the Ministry of Housing and Local Government said in March that it was working to formulate a policy that would help villagers obtain land titles and set out the future developmental direction of new villages.

In April Yeoh organised a two-day forum and exhibition on new villages in Kuala Lumpur. The 1,000 participants included community members, village heads and artists. They heard oral history interviews and folk songs collected from various clans, and saw hand-drawn heritage maps, reconstructions of old buildings, and plans for community art spaces, museums, and festivals.

“We would like to forge ties and promote discussion between individuals and groups taking part so that the concept of community art can be better organised and formed within and beyond the community,” Yeoh said at the time.

Whatever it is, the jobs created here must be given to the villagers

Petaling Jaya city councillor Leong Chee Cheng, who is helping the restoration project in Kampung Cempaka, hopes it can make the village more liveable and stop factories and industry encroaching on its land.

He says every part of the village is different, and each family has different needs. Lim says: “Here we have a strong social network and a strong bond of community. Everyone knows one another.”

Leong believes that by beautifying and revitalising the village, young people would be tempted back. Most of the villagers today are over 40 years old.

Like Yeoh, Leong has a vision of creating a community villagers can enjoy.

“We can promote farming, have a petting zoo and more education facilities, such as an exhibition centre for children to learn about river ecosystems. But whatever it is, the jobs created here must be given to the villagers.”

For Yeoh, the scheme’s goals are simple: to “breathe new life into new villages … let the villagers be independent and self-sufficient, and have a sense of belonging”.