Muslim artists rise to the 'no body' challenge

Artists in the Middle East have proved creative in the face of Islam's bar on depictions of the human body, as Fionnuala McHugh discovers

When curator Karin von Roques was a student in 1980s Germany, she became interested in Middle Eastern art.

In those days, Western teaching focused on classic Islamic work and halted in the 19th century (when, as Edward Said famously pointed out in his 1978 book Orientalism, the culture was hijacked by Western preconceived notions of exotic realms). Von Roques, however, was curious to know what was happening in the 20th century, so she began travelling through the region, beginning with Morocco; and she saw that there was an extraordinarily vivid art scene about which the West knew almost nothing and of which it was wary.

"In 1998, I made a poll," she says, on the phone from Bonn. "I asked about a hundred gallerists, in the United States, in Korea, in France, Beijing, why they didn't have these artists and there were two categories of answer: because they ban the human image or because it's such a different culture you need experts to prepare the field."

It was like with Chinese artists, von Roques says, when there was no interest until the Guggenheim staged the groundbreaking "China: 5,000 Years" in New York, in 1998.

We all know what happened with Chinese artists and there's a convenient German word (although von Roques doesn't use it) to describe the shift with regard to art from the Middle East: the zeitgeist would appear to be in its favour.

Apart from the New York Metropolitan Museum's extensive refurbishment of its Islamic galleries last autumn and the opening of the Louvre's new Islamic gallery last month, London's Victoria & Albert Museum is opening a contemporary photographic exhibition, "Light from the Middle East", in November. Closer to home, von Roques has curated an exhibition, "Written Images - Contemporary Calligraphy from the Middle East", for Sundaram Tagore's gallery here.

The show consists of 15 artists from countries - including Syria, Egypt, Iran and Iraq - where words and images have often had less serene association in recent years than those on view in Hollywood Road. In some of the works, the connection with calligraphy isn't immediately apparent.

Historically, Arabic calligraphy grew from a desire to honour the perfect language of God as set down in the Koran, and because of the concern about idolatry (which means the depiction of the human form is frowned upon, although it does exist in Islamic art), the script itself came to carry not just meaning but also aesthetic value. These contemporary artists are trained in that tradition but have moved beyond its formal boundary.

If you're reading this and groaning - not at the word Islam but the word contemporary - be at peace. This is not an exhibition of daubs by sensation-seeking art students. What strikes the viewer most is the unusual combination of a fresh perspective by artists who have been working, intellectually as well as emotionally, at their craft for years. The work is of museum standard and some of the names involved, unfamiliar though they may be to outsiders, are renowned in the region.

"Yousef Ahmad, from Qatar, is a very important artist; Chaouki Chamoun, from Lebanon, is also very important and Ahmed Mater is like a shooting star on the scene," says von Roques.

At 33, Mater is among the youngest in the show. He's a doctor in Saudi Arabia who uses X-rays to comment on the human condition, an innovative way of sidestepping the bar on the human form. On top of the illuminated bones he's placed text made from gold-leaf: the words literally shine on the hidden body.

"In the West, we have still lifes and landscapes," says von Roques. "This is not the case with the Islamic tradition. A lot of the artists have a classical education but they do something new with it. They work with non-image and the script is ornamental but not just decoration - there is something behind it, and it's fascinating to see how they choose ways to diversify that."

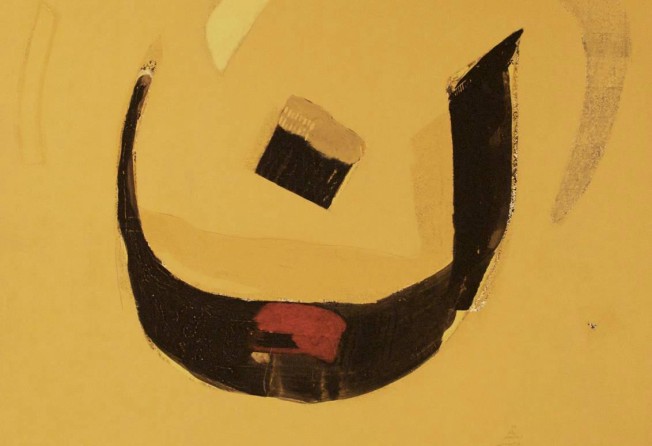

So Qatar's Ali Hassan constantly reworks the Arabic letter "nun" (equivalent to the Latin N) and its connection to surah [section] 68 of the Koran, which is entitled Nun and the Pen. Ahmed Moustafa, born in Egypt and now living in London, has written a doctoral thesis on the proportional system of calligraphy and devoted much mathematical, as well as artistic, thought to the relationship between the shape of a cube (as exemplified by the Kaaba in Mecca) and 99, the number of names for Allah. Lulwah Al-Homoud, from Saudi Arabia, bases her work on the ancient Indian multiplication table known as the Vedic square - not to box herself in but to find the possibilities of new space in geometry.

She's one of two women in the exhibition. The other is Golnaz Fathi, from Iran, whose work - created, in the classical style, with a quill - looks, to this outsider's untutored eye, strikingly sexual.

"Erotic, in a way, right?" agrees von Roques. "But I think she is not having this idea in her mind. She has had an education in classical calligraphy and that takes years, you have to repeat and repeat. And doing this incredible thing, with the pen on canvas, is like an act of meditation, between the conscious and the subconscious."

But wouldn't Fathi, who's 40, be horrified by such an interpretation? "It's often what I am thinking," admits von Roques, who speaks Arabic and Farsi but is not Muslim. "I go so deeply into this but still I have my Western-educated eye. I talk to the artists and sometimes they say, 'No, no, no - how do you have this idea?' But you still have the freedom to decide, it's about the interesting relationship between the painter and the person looking."

In a post-9/11 world, there has been no lack of genuine interest. "After what happened, prejudices and cliches were coming out," says von Roques. "But a lot of intellectual people said this cannot be the only side of the story."

"Written Images" was displayed in Tagore's New York gallery last autumn, his second exhibition curated by von Roques: "Signs - Contemporary Arab Art" had been shown in 2009 in New York and in 2010 in Beverly Hills.

"And people said, 'My God, we had no idea they have such fantastic art.' They were overwhelmed, they wanted more of these exhibitions," von Roques says. (One might also point out, vulgarly, that since Christie's held an auction in 2006, in Dubai, and Sotheby's held one the following year in London, the market in contemporary art from Islamic countries has shown a healthy upsurge.)

There is no reference, at least overtly, in the Hong Kong show to the Arab Spring. In January 2011, Ahmed Bassiony, a well-known artist von Roques had been working with on another project, was killed in Cairo's Tahrir Square. (His video work was chosen to represent Egypt at last summer's Venice Biennale.)

Islam is itself a divided house although von Roques has little time for such sub-labels ("Sunni, Shia, Alawite - very, very often this whole thing is politically manipulated") and neither do the artists.

"They all say, in the first place we are human beings and we are artists, influenced by our culture. They feel unified, gathered together. To give that sense of perspective is why you do such shows."

Written Images - Contemporary Calligraphy from the Middle East, Sundaram Tagore Gallery, 57-59 Hollywood Road. Until Nov 4