Peter Paul Rubens' paintings are more show than substance, London exhibition affirms

Was Peter Paul Rubens, focus of a big London show, all style but little moral substance? Jonathan Jones takes a look

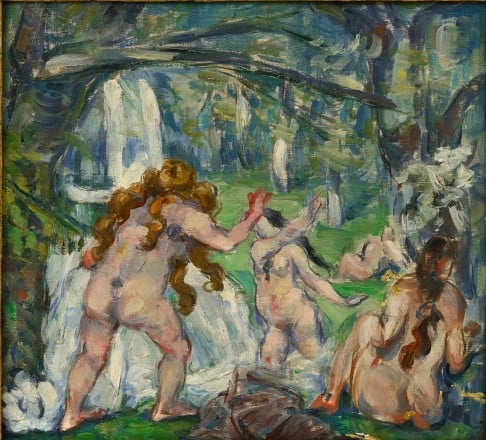

The first art blockbuster of 2015 will see Peter Paul Rubens riding into the Royal Academy of Arts, probably in a golden chariot pulled by four leopards with the muse of painting at his side, a bevy of plump nymphs hailing his triumph and the gods declaring his apotheosis from fire-fringed clouds.

The art of this Flemish painter - who decorated palaces and banqueting halls, went on diplomatic and spying missions, owned a landed estate and somehow found time to fill the Old Master galleries of the world with colossal canvases of boar and lion hunts, characterful portraits, epic history paintings and visceral sea monsters in the near 63 years he lived from 1577 to 1640 - is a world in itself. Rubens satisfied the horror vacui (fear of empty space) of a generation of absolutist monarchs.

From his cycle of 24 enormous paintings that celebrate the life of Marie de' Medici in the Louvre to his ceiling of the Banqueting House in London with its portrayal of James I being welcomed into heaven, Rubens is such a stupendous flatterer that you forget the overt cynicism of the propaganda and just wallow in his scintillating light, swirling space and swagging clouds.

But is Rubens, for all his inexhaustible brilliance, really the artist among artists the Royal Academy takes him to be? He used to be called "the Prince of Painters", its publicity reminds us. This old term of praise is, today, more like a warning light. Rubens moved in high society, a courtier as much as an artist. He is, ultimately, a supreme decorator who never touches profundity.

However many massed cherubs blowing trumpets of praise the Royal Academy puts on tube and rail posters in the New Year, he will never be a Rembrandt, Caravaggio or Velazquez. These three geniuses all lived in the same age Rubens dominated. But where he created seductive confections, they tell a more serious truth.

I love Rubens' portrait of his sister-in-law, Susanna Lunden, in the National Gallery in London, for instance. She's a sweet girl, the painting is gallant. But go and see Rembrandt's portrait of Hendrickje Stoffels in the same museum and you're in a different world: not gallantry but deep human reality. And that is quite a mild comparison between Rubens and Rembrandt. What painting by Rubens can be set alongside Rembrandt's late self-portraits? If Rubens looked at himself that hard, his hat might have fallen off.

The very energy of Rubens has something brittle about it. He can't stop for fear of looking into the dark. He seems terrified of Caravaggio's shadows, Rembrandt's eyes, Velazquez's mirror. His art endlessly moves on, through a bewildering range of genres. It also assimilates a staggering variety of influences.

Centuries before post-modernism, Rubens was sampling artists. In his 1632-35 painting The Judgment of Paris, the goddess Athene has left her shield propped against a tree. It has the face of the monstrous snake-haired gorgon Medusa on it. Rubens has artfully made this shield a quotation - it is a copy of Caravaggio's painting of Medusa's severed head.

Borrowing from Caravaggio is no crime - but if only Rubens had taken that example more seriously. For him, the face of Medusa is just part of a rich panoply of flesh and myth. For Caravaggio it is a terrifying mask of self-recognition.

Rubens moved in high society, a courtier as much as an artist. He is, ultimately, a supreme decorator who never touches profundity

This sense of avoidance gets stronger the more you see of Rubens' paintings. And there are so many. His Antwerp workshop employed assistants galore. Many became major painters: Van Dyck is his most brilliant protege. Many paintings by Rubens have details added in by specialists - Frans Snyders did the fruit and game.

Rubens had his own reasons to be scared of artistic darkness. His parents fled Antwerp to get away from its savage religious wars between Protestantism and Spanish Catholicism. Two years before he was born, the city was savagely sacked. So it's not true that Rubens was an aristocrat with no sense of suffering. Horror was part of his birthright.

Look a bit harder at his paintings and they are full of images of cruelty and violence. The face of the war god Mars contemplates a group of children playing, and his eyes tell you he just wants to kill them. A youth is killed by a monstrous bull that crashes out of the sea in a broth of foam.

Rubens sees psychological darkness, but insists it can be defeated by civilisation. His art is optimistic. That was why kings and queens paid through the nose for it. Sweeping us up in its impulsive brushwork, leading us on roller-coaster rides of painterly prowess, this is a Baroque entertainment of the highest order.

The faces of war, chaos, death and poverty can be seen in the vortex, yet their shock is muted under spurts of colour, overwhelmed by a festival of artistic joy.

In the age when Rubens was most revered, from his lifetime to the 19th century, his balance of good and evil, chaos and order, was admired as a triumph of sanity. Today, Rubens seems too sane to be one of the greatest artists. He portrayed his first wife, Isabella Brant, many times, always with the same sweet smile on her face. She died from plague at the age of 34, yet in his final portrait she is still smiling. For Rubens the show must go on.

Guardian News & Media