Forerunners of YouTube - Art Institute of Chicago's video collection is unofficially collated online by a grad student

Chicago museum's little-seen film and video collection is getting an unofficial airing online

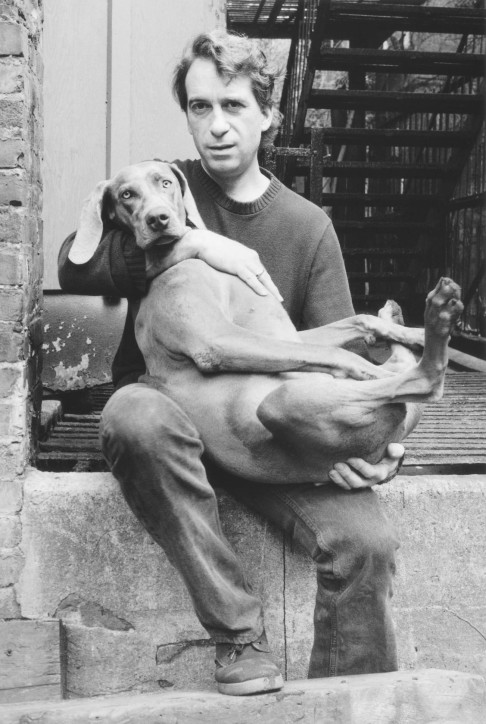

American artist William Wegman is probably best known for his photographs of Weimaraners. For decades now, he has been able to coax his pet dogs to pose stoically before his lens, offering a steady, curious, tolerant gaze to the camera despite the oddball scenarios in which they are placed.

Less common are Wegman's early video works, including Two Dogs and Ball, which is part of the collection at the Art Institute of Chicago. The film is less than three minutes long. In it, a pair of Weimaraners sit calmly side by side, their eyes locked on the movement of a tennis ball that someone is handling off-screen. The dogs are rapt and their "performance" is mesmerising, a little creepy - and hilarious.

The video has been watched more than 73,000 times on YouTube, where it feels like a natural fit because, well, dogs.

It is one of several works of film and video you can find online that are part of the Art Institute's collection. Only recently have they been organised - unofficially - into a single YouTube playlist, courtesy of Chicago-based critic Kevin B. Lee, who is pursuing graduate studies at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. This is not the first time Lee has found himself hurtling down a YouTube rabbit hole. Last year he made a film called Transformers: The Premake, which is a cunning critique of the blockbuster and its director Michael Bay, made up of video scraps shot by fans stalking the film's on-location action.

With his latest project, Lee has uncovered a fascinating collection of short abstract art films, almost all of which are impossible to view at the museum because they are not on any kind of permanent display.

"I didn't know who William Wegman was, or who most of the artists in the collection were for that matter, before I started this project," Lee says. "When I saw Wegman's videos, I felt like I had discovered the father of the YouTube video 30 years before YouTube ever existed."

Other works feel very much like precursors to today's language of the internet. Richard Serra's Hand Catching Lead from 1968, featuring a dirty palm opening and closing over and over again, is basically a GIF.

"You see these new media or YouTube tropes manifesting 30 or 40 years before YouTube. And yet if you asked most people if they knew of these films or these artists, they would tell you no."

So why are these films kept out of sight? Physical exhibition space is limited and not surprisingly "they would rather put their Picassos and their Andy Warhols and their brand-name artists up", Lee says. "Film and video art still kind of has a secondary status. But the museum has a substantial collection. It now stands at a little over 100 works."

When I saw Wegman’s videos, I felt like I had discovered the father of the YouTube video 30 years before YouTube ever existed

Lee bought a catalogue that listed all the works in the collection and "on a whim I started to do some casual YouTube searching. I ended up finding more than half of them on YouTube in some form or another," he says.

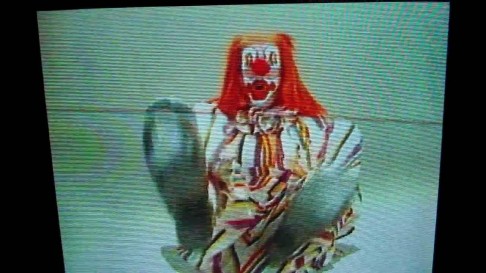

He has corralled the videos into a playlist on YouTube, sorted by popularity. So what is out there? "There are variations of any given video. That's the weird thing about YouTube - things start to take different forms," he says.

"The video may be the work itself that's been uploaded in its entirety. Or it could be someone went to the museum where the work was playing, recorded it on their phone and then put it on YouTube." That's a no-no, but it happens.

"And then there's this third category, which I like to call 'remixes and remakes', where people just make their own versions of the work, for whatever reason."

Museums - at least some museums - have gradually made peace with the idea that people are going to pull out their phones. The Museum of Modern Art in New York has an app that actually encourages this: "Snap and share your MoMA experience," it instructs. Instead of fighting social media, MoMA is co-opting it and branding it.

"You can't stop people from doing what they want to do, which is capture things on their phone," says Lee, "and YouTube becomes a kind of facilitator for that impulse. It creates this weird situation where the most visible trace of this artwork is the YouTube documentation, no matter how distorted it is.

"I go back and forth as to whether this is good or not. Obviously there's something lost when you have this thing, your phone, that's between you and the experience you're having. At the same time, it then gets shared with other people - and other people now have access to it."

The films and videos in the Art Institute's collection are arty, strange and unexplainable. Some are beautifully eerie, like Paul Sharits' Shutter Interface from 1975, which looks like an old TV test pattern - the vertical bars of colour flashing over an echo-y sound that can only be described as "alien wind tunnel".

"This work is something that even most cinephiles don't know about. It's this whole tradition of film and video as practised by gallery artists who use film as an extension of their practices in painting or sculpture or drawing."

Here's what you'll notice right off the bat: digitally wandering through the Art Institute's video collection feels quite different from the traditional museum experience. "At a museum, it's more of a one-way experience. You go there, and you're supposed to take in the work and have this reverential relationship to it. But I see YouTube being more of a feedback channel, where people can comment on these videos and make their own versions," Lee says.

The Art Institute is aware that Lee has organised these videos into one spot. "I met one of the curators yesterday, actually. I was a little nervous because I was afraid that after showing them the list of videos, they would then go through and systematically have them pulled down, one by one," Lee says.

Instead, "they were fascinated. They actually thought that I was performing a service for them, in terms of understanding how their collection is being manifested outside the institution and how people are engaging with it.

"But it is still a critique, in many ways, of the museum's management of its collection and the opportunities that are lost when the works are not available to be seen - and what has been happening organically on YouTube to compensate for that."

Chicago Tribune