Artistic freedom in Hong Kong: self-censorship, culture of fear growing, creatives say

- A number of politically oriented artists in Hong Kong are turning to activism to ward off threats to their freedom of speech

- But others have confidence in artists’ ability to express themselves

Wen Yau’s eyes were covered with a blindfold made of the China flag. Slowly, carefully, she inched her way forward with one hand outstretched, feeling her way through space. In the other hand she held a blank sign – a silent protest against self-censorship.

She had performed a similar piece back in 2014 during the Occupy Central mass protest, but felt compelled to blind herself once again for others to see.

Wen Yau was among a group of like-minded artists, all holding blank signs, who recently gathered at Tai Kwun, a prison-turned-arts-venue in Hong Kong’s Central district. They were there to express their discontent with two events that had transpired earlier this month: the cancellation of Chinese dissident artist Badiucao’s art show at the venue, and Tai Kwun’s initial ban on hosting talks by author Ma Jian, another Chinese dissident, before an abrupt about-face.

Wen Yau says that a general feeling of self-censorship is growing in the city’s cultural scene and is akin to Taiwan’s “white terror” period of political suppression that lasted for 38 years until 1987.

“It is something that is like a ghost or spirit that is haunting you. You cannot really see or touch it. Because it is intangible, you really feel scared,” she says.

She is not alone in her sentiment. A number of the more politically oriented artists in Hong Kong are turning to activism to ward off threats to their freedom of speech.

Kacey Wong is a visual artist and a founding member of organisations including Art Citizens and the Umbrella Movement Art Preservation. He tells the Post that once an artist realises that their work involves social or political issues, the term “art activism” becomes useful since it suggests an immediate connection between art and society.

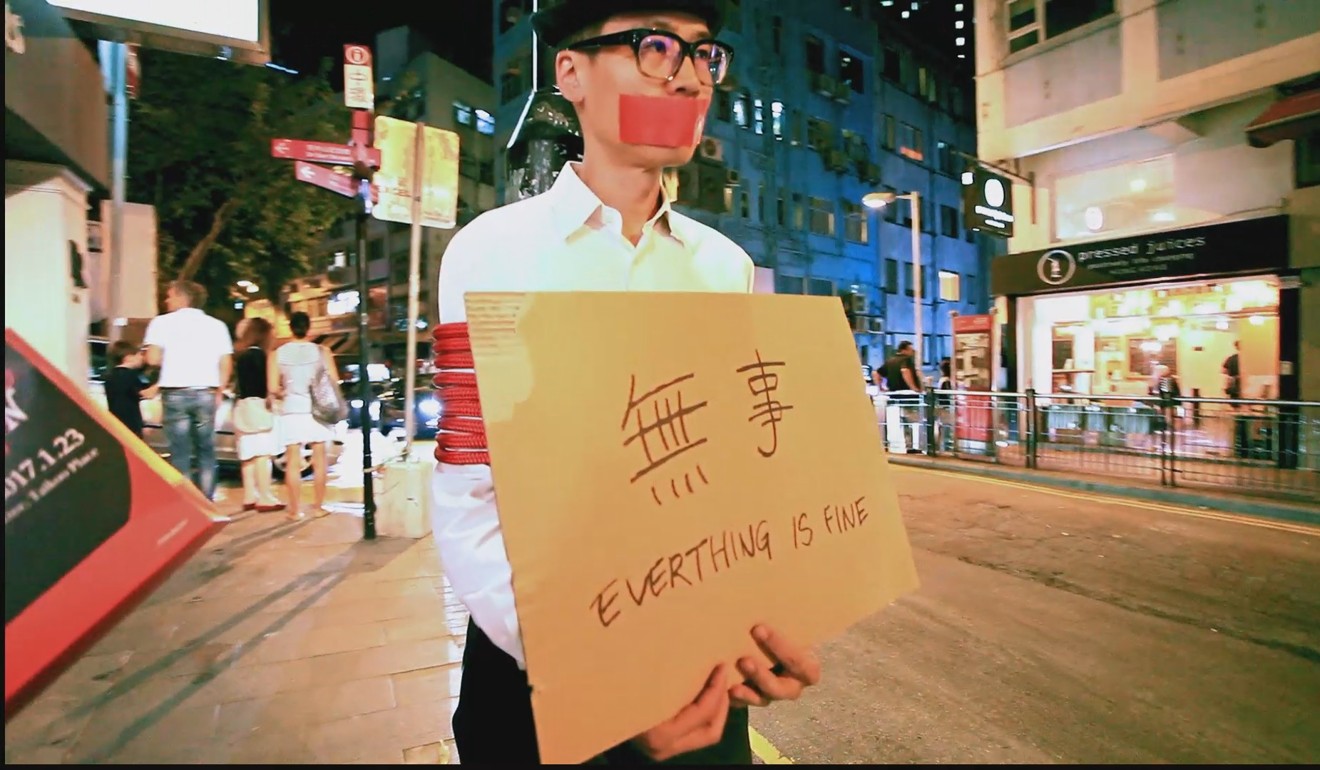

Following the 2015 disappearance of five Hong Kong-based book publishers, who eventually turned up in the custody of Chinese authorities, Wong tied himself to a lamp post with his mouth taped, holding a sign in English and Chinese saying “Everything is fine”.

He says the work is still relevant today in light of recent events.

“That piece of work is my frustration towards the society I’m in right now – the threat and the suppression – the totalitarian government is already here. There is no more fall of Hong Kong. It already fell,” he says.

Leta Hong Fincher, author of Betraying Big Brother: The Feminist Awakening in China, believes pressure can sometimes come from non-government sources. A speaker at this year’s Hong Kong International Literary Festival at Tai Kwun (during which dissident Ma also spoke), she explains that the venue, for instance, is supported by the Hong Kong Jockey Club, which provides funding for a variety of community projects in the city.

“A lot of the problem is that really influential business leaders themselves are just looking out for their own business interests,” Fincher says. “In the case of Ma Jian … clearly those were business decisions. There are always going to be spaces for [such] artists and writers, it’s just that they are not going to be the most mainstream commercial spaces.”

Fincher says that the worst of the crackdowns on freedom of speech are still happening in China. She worries, though, that Chinese artists and writers who were for a long time able to find refuge in Hong Kong are not finding it the sanctuary it used to be.

“Unfortunately I’m sure we’re going to see a lot more of that. I mean there are so many areas in which freedoms previously taken for granted in Hong Kong are being eroded very rapidly – eroding press freedoms, eroding academic freedoms – so this is something that people really have to really fight back against. It is a very worrying development,” she says.

These recent developments reflect Beijing’s more hardline approach to the city as it urges Hong Kong to introduce a national security and anti-sedition law that many people, including businesses, fear will curb more freedoms, as well as the city’s competitive advantages.

Freedom of expression, along with Hong Kong’s liberal tax regime, are among the main reasons the city has become one of the world’s largest art hubs. This may explain why visual artists have been among those most vocal on the issue of censorship.

But it is not just artists and cultural actors feeling the squeeze. Prominent pro-democracy politician Emily Lau Wai-hing, a former chairperson of Hong Kong’s Democratic Party, tells the Post about the feeling of fear and self-censorship in society.

“I think that we are under siege from all sides. Freedom of expression, freedom of the press and self-censorship, all these things [happening] are very worrying,” she says.

“So many people told me that their emotions were like in a roller-coaster, rocking up and down, and people were so angry. I think we have to fight this fear, and this feeling of impotence.”

Last July, Chinese president Xi Jinping warned Hong Kong not to undermine Chinese sovereignty by crossing the “red line”, which was defined as any challenge to the power of the central government.

“We call it the ‘red line’ … And what is that red line? Nobody knows,” Wong says. “It is not like there is a rule book written in stone, so everybody is taking a wild guess. That is why we are seeing all this censorship in literature, in fine arts.”

History tells us that there are always artists who are able to challenge censorship by figuring a way around systems and rules

Yeewan Koon, associate professor and chair of the fine arts department at the University of Hong Kong, says that self-censorship can be a bigger threat than conventional censorship because of how it adds to a climate of fear.

“I am not sure what will happen in the immediate future in the creative world in Hong Kong, but history tells us that there are always artists who are able to challenge censorship by figuring a way around systems and rules,” she says. “We must also recognise that the art world exists far beyond conventional institutions and government-supported spaces.”

Koon says she does not want to play down the importance of what is happening to Hong Kong, but she believes in the creativity of artists to not let censorship stop them from making art.

Although some artists worry about being able to express themselves in the future, not all of them are pessimistic. Hong Kong artist Michelle Lee says that although her work is not very political, she sees the situation as flexible.

“It is like decoding something. You need not say it very directly, but people sense your work from little details or like symbols and metaphors. So I think as long as you are flexible, you can still find a place to work politically. I don’t think it is a very big constraint on me at this moment,” she says.

“We need to go into the cracks and try to work so that voices can be extended and discussion can reach different people and not be covered.”