This group is saving Tibetan traditional architecture from destruction and decay

- She is from Portugal, he is from Japan, and for 20 years the Tibet Heritage Fund they work for has restored Tibetan structures from Lhasa to Mongolia

- Team members often spend months at a time in remote spots and harsh conditions; they pass on skills to the locals they work with

The 1997 film Seven Years in Tibet follows the adventures of Austrian mountaineer and former Nazi SS officer Heinrich Harrer, who escaped a British prisoner of war camp in India and travelled more than 1,200km (750 miles) to Lhasa on foot and by yak at the tail end of the second world war.

It was in the Tibetan city that Harrer, played in the film by a fresh-faced Brad Pitt, met and became the 14th Dalai Lama’s English teacher and lifelong friend.

Harrer, who renounced Nazism before he died in 2006, wrote the 1952 book on which the film was based.

But to a group of contemporary Tibetan heritage experts, it is Peter Aufschnaiter, Harrer’s fellow escapee, who has the more memorable story. That’s because Aufschnaiter laid the groundwork for the group’s mission to rescue traditional Tibetan architecture and craftsmanship from the brink of extinction.

Aufschnaiter, an Austrian engineer and cartographer, had lived in Tibet before the war and spoke the language, helping him and Harrer pass safely into the region. He was hired by the Lhasa authorities to plan irrigation channels, conduct the first detailed survey of the city and produce a proper town map. He was forced to leave Tibet for good, however, after the Chinese army marched in and took over in 1950.

Nearly four decades later, in 1987, German backpacker André Alexander arrived in Lhasa on a first visit. As the young historian learned more about Tibet’s history, he became concerned at the rate at which old buildings were being razed. In 1993, he and a friend set up the Lhasa Archive Project to keep a record of the buildings before they disappeared. Their most important reference? Aufschnaiter’s 1948 map.

Many of the 869 significant buildings Aufschnaiter recorded had fallen victim to China’s Cultural Revolution (1966-76), which aimed at purging “old ideas, old culture, old customs and old habits”. But to the team’s dismay, nothing was being done to preserve the remaining valuable structures, including 17th-century mansions in the old Barkhor area surrounding the Jokhang Temple.

By the mid-1990s, the archive had attracted a few more dedicated campaigners, including a Portuguese artist called Pimpim de Azevedo.

“We realised that documenting was not enough. Something else needed to be done,” she says. “So we founded the Tibet Heritage Fund in 1996 and started talking to the Lhasa municipality about restoring buildings in the old city. The mayor arranged for the cultural relics bureau to work with us. In four years, we restored 13 residential buildings, all built in traditional materials with very refined styles.”

Azevedo, who trained with master craftsmen in Lhasa, advocates a community-based conservation approach to ensure traditional know-how gets passed on locally. She was speaking to the Post in Hong Kong, where she and Japan native Yutaka Hirako, programme director at the fund, catch up with administrative and fundraising work when it is too cold to work in the Himalayas.

The fund has worked on courtyard houses in Beijing, Tibetan monuments in the Chinese provinces of Sichuan and Qinghai, and in northern India.

Of all the sites Azevedo has visited, she found the physical demands of the 2003-07 restoration of the Sangiin Dalai Tibetan Buddhist monastery in Mongolia to be the harshest. The remoteness of the area, 700km from the capital Ulan Bator, also made the ambitious programme a logistical nightmare.

“In the first three years, we travelled on a public van that would take as many as 26 hours, non-stop, to go from Ulan Bator to our project site. The capacity was for 11 people, including the driver, but for each journey that I made, there were about 21 people inside,” she recalls.

“We stayed in an abandoned government building without central heating. The only water tap was located about 150 metres from the house and the public toilet was even farther away. We relied on one donated generator. Because of limited funds, it only operated for two to three hours a day, if at all. In the last two years, we did not have enough money left for petrol and so we used candles on most days.”

The conditions made a challenge of even the simplest restoration work on the 18th- to 19th-century monastery complex, which was a mix of Tibetan, Chinese and hybrid styles.

The fund wanted to leave behind a sustainable local industry. That saw them restart a long-abandoned kiln used for making the unique blue bricks and elaborate tiles used in the original monastery buildings. “Because of the lack of skills locally, we had to bring artisans from Beijing and Qinghai to provide training,” Azevedo says.

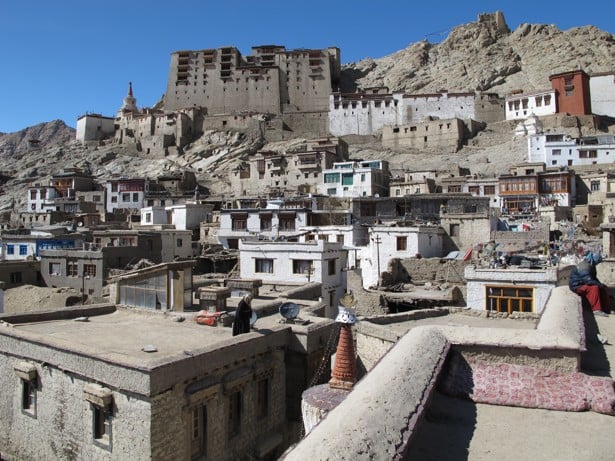

The fund has always focused on vernacular buildings because they are the most at risk: the unobtrusive low-rises below the looming Potala Palace in Lhasa, for example, or the sand-coloured dwellings overlooked by Leh Palace in the Ladakh region of India.

As I crossed the first mountain pass on a bus, it seemed to me that I had arrived at the sky. At that moment I fell in love with Tibet and the Himalayas

There are advantages to working with these types of old local houses. The arrangement helps the team get closer to the local community and understand living conditions, customs and behaviour, Azevedo says. The team also discovered that traditional buildings tend to be more resilient to the region’s extreme climate conditions and earthquakes.

It has been over two decades since Azevedo first set foot in Tibet, but she has total recall of that moment in 1987 when she fell under the region’s spell.

“I was planning to come to Hong Kong overland from Nepal. After crossing the Nepalese border into Tibet, I walked up to Nyalam, located at around 3,750 metres above sea level, and the landscape was amazing, and all the people I met were so friendly and cheerful,” she says.

“Later, as I crossed the first mountain pass on a bus, it seemed to me that I had arrived at the sky. At that moment I fell in love with Tibet and the Himalayas.”

The fund has not been involved in any projects in Tibet since 2000 when its partnership with the Lhasa government ended. Azevedo refuses to be drawn on why, saying the matter is too sensitive. However, Unesco has said that the Chinese government’s restriction on foreign access to a region affected by long-running ethnic tensions has made it difficult for Western experts to participate in Tibet’s heritage projects.

As far as the Tibetan Heritage Fund’s work is concerned, there is plenty for it to do outside Tibet’s contemporary political borders.

Hirako, who has led conservation projects that have won Unesco best practice awards, has been conserving Tibetan buildings in the Indian town of Leh since 2012. In 2015, the fund also completed a newly built Central Asian Museum in the town, a historic Tibetan Buddhist pilgrimage site, that melds contemporary and traditional architecture and features displays about the region’s past position as a multicultural crossroads.

Sheer willpower can overcome the lack of resources, discomfort and long hours spent on the road, but the fund’s biggest test arrived in 2012, when Alexander suddenly died from a heart attack. He was only 47.

“The death of André was a shock,” Azevedo says. “We were close friends and creative companions for 25 years, and I was numb with the pain. Soon after his death, I needed to make a decision and a statement regarding the future of our organisation. We decided to continue the work that we loved and cared about, because it wasn’t just about us but about keeping this unique culture and architecture for a little longer for future generations to enjoy and appreciate.”

Hirako, too, says he is devoted to the region. His first trip to Tibet was in 1996, when he cycled from Yunnan in China, where he was studying Chinese, to Lhasa for two months in the winter.

“It was recommended that you undertake this trip when there is snow on the ground because there is no water source for 300km of road,” he says. “I went back to Japan after my studies but went back to Tibet shortly afterwards and joined [the Tibet Heritage Fund]. That was 1998.”

It helps that he likes the food in Leh. “Ladakhi cuisine is mostly boiled food. Thukpa [noodle soup], momos [dumplings], chutagi [soup with dumplings] and skyu [like a pasta stew] are the Ladakh specialities that we eat all the time. Also, tsampa [roasted barley flour] is my favourite breakfast,” he says.

“I prefer Ladakhi food to the more overpowering Indian dishes, so I can survive easily there. I do miss east Asian cuisine sometimes so now is the time to fill up.”

For more information on the Tibet Heritage Fund, visit tibetheritagefund.org