The United States’ imperial reach, from Mexico to the Philippines to the present day, dissected

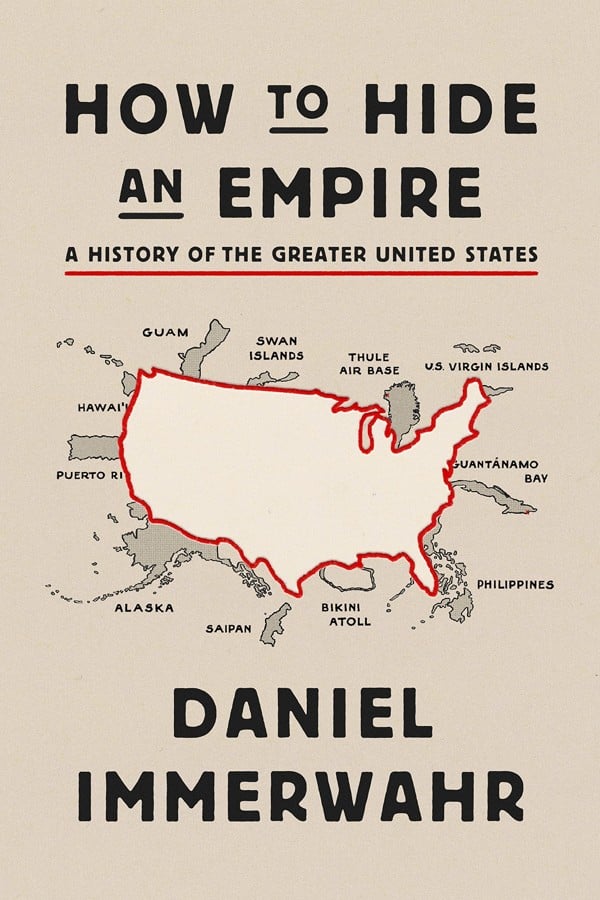

- From Alaska to Puerto Rico to 94 guano islands, Daniel Immerwahr examines the acquisition of territories by the US

- In How to Hide an Empire, he argues that the US’ empire persists today in its overseas bases, dominance of trade and willingness to project force

How to Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater United States , by Daniel Immerwahr, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 4/5 stars

Asians, in general, need little convincing that the United States is, if not an empire per se, at least imperial. So the title of How to Hide an Empire might be seen as an attempt at irony.

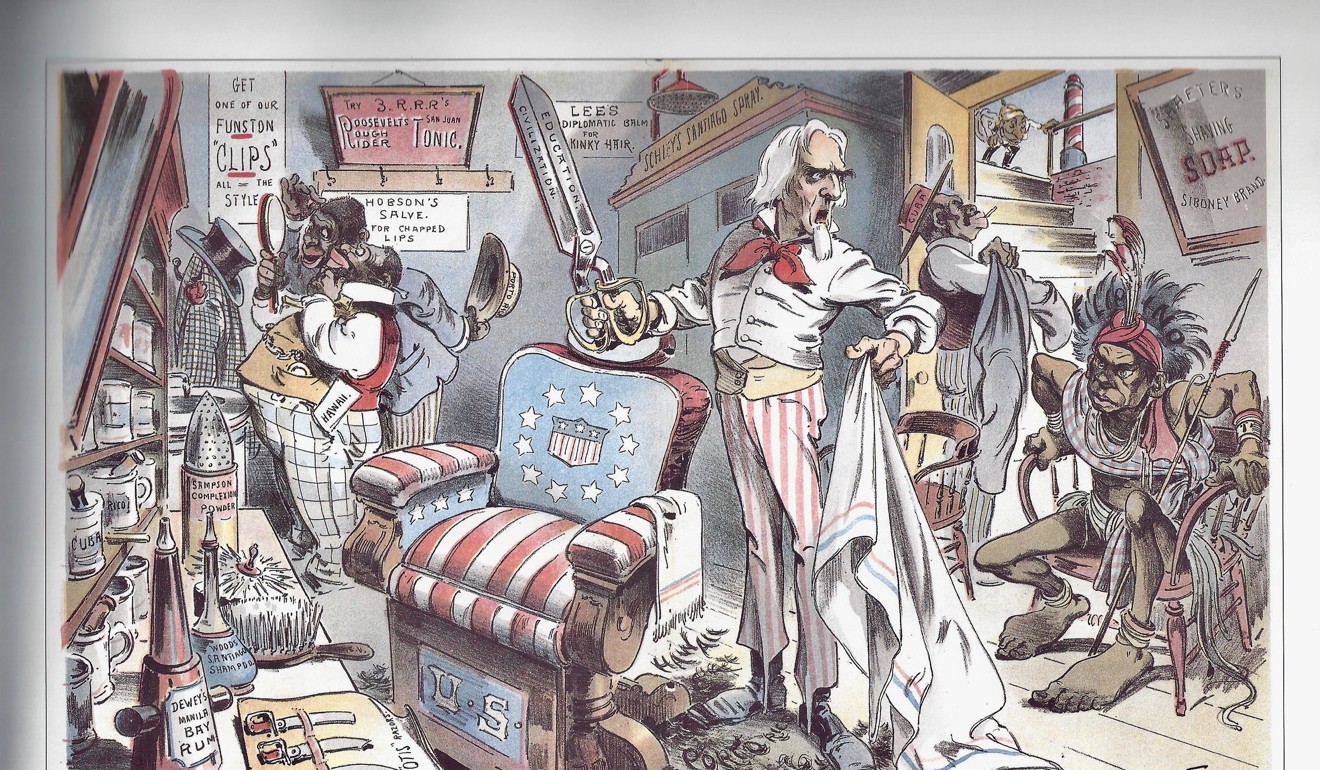

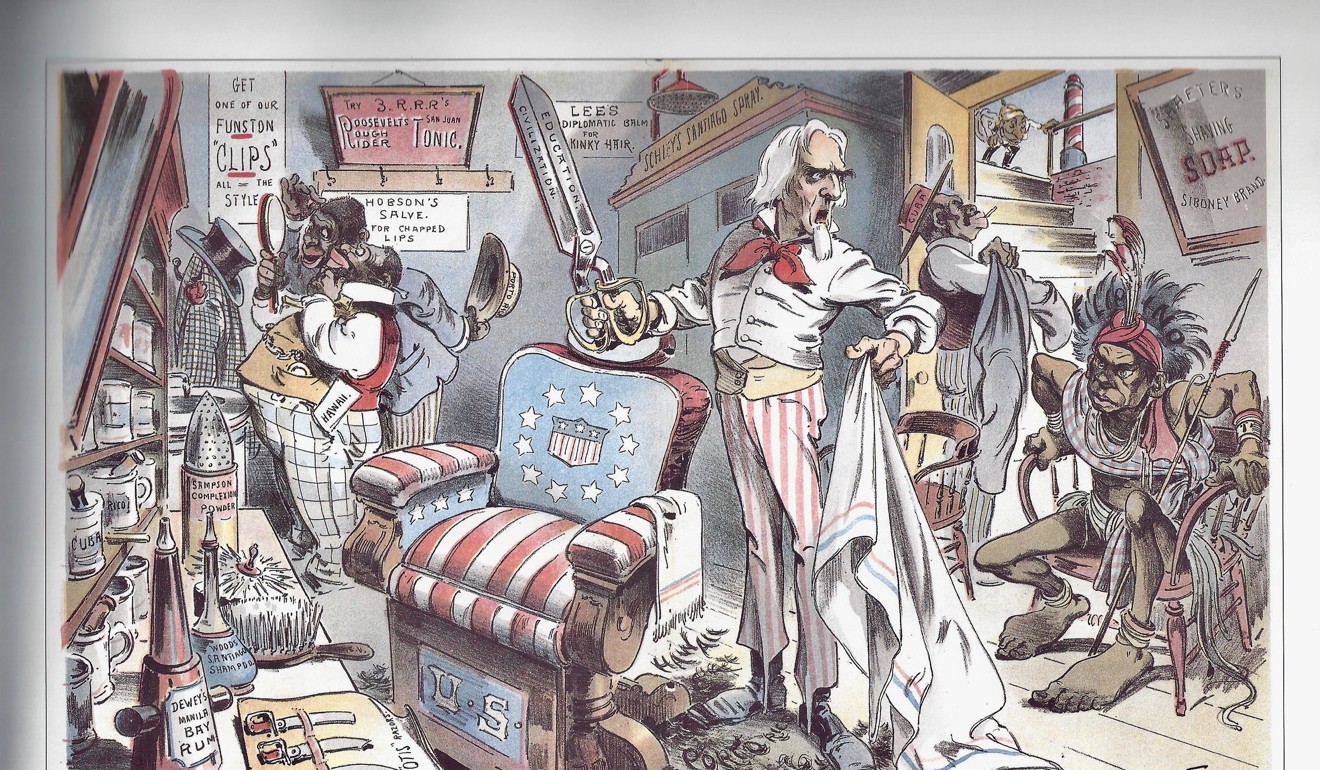

Daniel Immerwahr, admittedly, wasn’t writing for an Asian audience. His book is targeted squarely at Americans. It’s not that “empire”, as a concept, is entirely alien: conventional wisdom, to be fair, usually acknowledges that the US had at least a dalliance with empire, which was how the country ended up with the Philippines for just under 50 years.

Whether this was really empire, or just a phase thrust upon it before global decolonisation caught up, is a matter of (often disingenuous) debate.

But Immerwahr not only presses the case that the post-war US is also, via its overseas bases, its willingness to project force, and dominance of such things as industrial standards, global trade policy and the English language, still an empire – that, in short, empire is as empire does – but that the earlier, 19th-century Western expansion up to and including the acquisition of Alaska and Hawaii were also imperial.

Nor, he argues, does the fact that these territories ended up as states make it any less imperial.

It is probably the case, as Immerwahr notes, that Americans – other than possibly the descendants of those who had inhabited those lands for centuries before – do not usually consider this Western expansion imperialistic: it is perhaps a matter of definition.

The models of empire most often used as references, and the one in which the Philippines fits, are those of Britain, France and Spain with their far-flung colonies. America’s westward expansion through contiguous territory echoes that of the Russian empire that began a couple of centuries earlier and went largely in the other direction.

One thing that distinguishes American empire from others is that America was usually wary about ruling other peoples, not to mention integrating them into the US proper.

With US forces occupying Mexico City in 1848 at the end of the Mexican-American war, the US might have taken the entire country, but, as Immerwahr explains, it instead “annexed the thinly populated northern part of Mexico (including present-day California, Utah, New Mexico, and Arizona) but let the populous southern part go.

This carefully drawn border gave the United States, as one newspaper put it, ‘all the territory of value that we can get without taking the people’.”

Immerwahr is particularly good at noting the contradictions that arise when trying to apply the US Constitution to places that are American but not part of (or one of) the United States.

The 14th Amendment’s citizenship guarantee to anyone born in the United States doesn’t apply to the unincorporated territories. In them, citizenship came late and only after struggle. What is more, it arrived as “statutory citizenship”, meaning that it was secured by legislation rather than by the Constitution and could therefore be rescinded.

Puerto Ricans became citizens in 1917, US Virgin Islanders in 1927, and residents of Guam in 1950, although, in all cases, because their citizenship is statutory, it can be revoked.

Filipinos were never granted citizenship, but they were “US Nationals”. Immerwahr writes: “West Coast labour unions nervously eyed the tens of thousands of Filipinos who competed with whites for agricultural jobs – since Filipinos were US nationals, no law stopped them from moving to the mainland.”

The United States is not alone in this, of course, as residents of Hong Kong and other erstwhile British-ruled territories are well aware.

Possibly the most illuminating parts of the book are those that deal with what Senator William Henry Seward (who later brokered the purchase of Alaska) referred to as “ragged rocks”: the US had an unquenchable thirst for nitrogen fertiliser and as a result coveted the so-called “guano islands” to be found in the Pacific and Caribbean, such as on Midway Atoll in the Hawaiian chain.

Under the eponymous 1856 act, “whenever a US citizen discovered guano on an unclaimed, uninhabited island, that island would, ‘at the discretion of the President, be considered as appertaining to the United States’”.

And so, “by 1863, the government had annexed 59 islands. By the time the last claim was filed, in 1902, the United States’ oceanic empire encompassed 94 guano islands”.

Sometime later, after the islands had been stripped of their nitrogen rich bird droppings, the US government realised that they were strategic.

“Aviation meant they could serve as landing strips; radio meant they could host transmitters. In 1935 the State Department announced that it was annexing Baker, Howland, and Jarvis Islands in the central Pacific.

Two days later, it hastily rescinded the announcement,” Immerwahr writes. “The United States didn’t need to annex those islands, officials clarified with embarrassment. A consultation of the records had revealed that it already owned them.”

While the islets in the Pacific are on the whole far away from anywhere else that might claim them – not that there weren’t arguments – there are some in the Caribbean which the US still holds and which are under dispute. China, some might remark, at least has the benefit of a nine-dash line.

How to Hide an Empire has a bit of a circular “when you’re a hammer, everything looks like a nail” feel: if one defines all attempts at control as exercises in imperialism, then that word becomes synonymous with power projection and bullying. Perhaps it is, but then one loses potentially important distinctions.

While it is true, for example, that Puerto Rico is the result of America inheriting Spain’s imperial mantle, its status as a US territory with US citizens yet without representation in the federal government, and whose self-rule is at the pleasure and whim of Congress, is in this not substantively different than Washington, DC.

Something other than explicitly empire might result in some of the situations and conditions that Immerwahr describes.

But Immerwahr succeeds in creating a notion of the “Greater United States”, a concept which rarely if ever enters public dialogue. Whether it will be met with more than a shrug remains to be seen. Out in East Asia, however, How to Hide an Empire might instead result in atlases being cracked opened in an attempt to find the Swan Islands.

Asian Review of Books