How Donald Trump became president and can America be great again? A look at the history

- In ‘If We Can Keep it’, author Michael Tomasky offers a highly readable lesson in US history and politics arriving at Trump in power today

- He doesn’t blame Trump for where the US is right now, but credits him with lighting the fuse that exploded into partisanship

If We Can Keep It, by Michael Tomasky. Published by Liveright. 4 stars

Like his earlier four-page letter of absolution, US Attorney General William Barr’s press conference last Thursday quickly degenerated into fan fiction.

Back on planet Earth, Russia wanted to boost Team Trump, his minions were ready and willing and the president was predictably obstructive. Instead of indicting him, Bob Mueller damned him. On Good Friday, the president was left to tweet profanely and profusely. To quote John Milton, “Better to reign in Hell than serve in Heaven.”

And entitlement is not limited to the Oval Office. Operation Varsity Blues and Charlie Kushner buying Jared a seat at Harvard are vivid reminders that college admissions can be rigged for the sake of mammon and parental posterity.

Enter the Daily Beast writer Michael Tomasky with If We Can Keep It, a look at America’s journey to this point. Under the subtitle, “How the Republic Collapsed and How it Might be Saved”, Tomasky offers a highly readable lesson in US history, politics and civics. He contends that partisanship, not unity, is the country’s political state of nature, and furnishes suggestions as to how we might step away from the brink.

Tomasky does not blame Trump for how we arrived at this juncture, but credits him with lighting the fuse. His narrative begins with America’s Big Bang: the revolutionary war and the constitution. He describes how the structures of government served to check ambitions, twist and reflect popular will and distort outcomes – all at the same time.

As expected, the electoral college and a Senate that awards representation regardless of population do not earn high marks. The book emphasises that while the founding fathers decried faction, political parties emerged as the operative vehicles to steer the republic into and around tumult and turbulence.

In 1800, the House of Representatives took 36 ballots to break a deadlock and elect Thomas Jefferson as president. The war of 1812 saw the death of John Adams’ and Alexander Hamilton’s Federalist party. Come 1820, Congress adopted the Missouri Compromise, kicking the can down the road in the face of duelling demands between north and south over slavery.

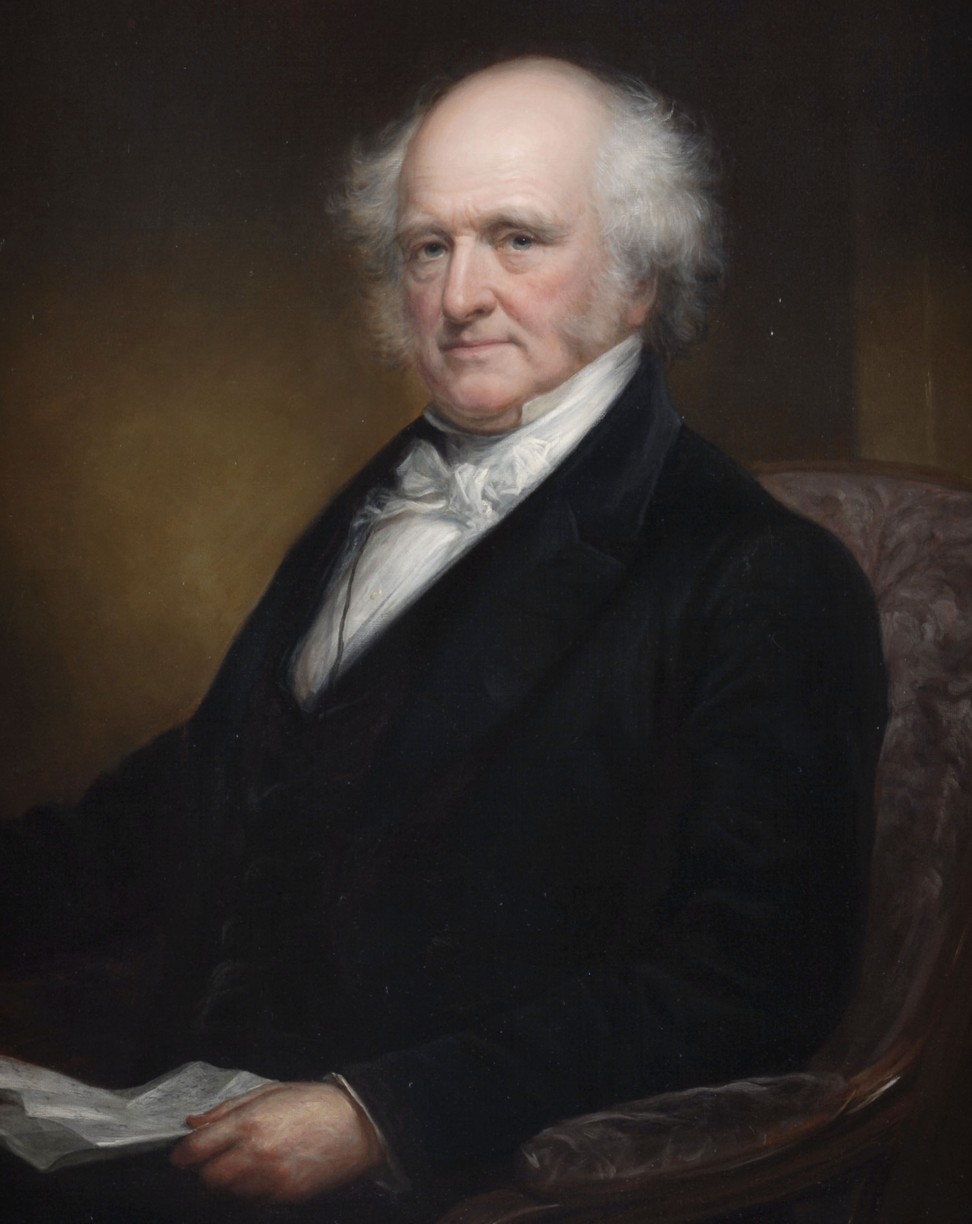

In Tomasky’s view, it was New York’s Martin Van Buren – who succeeded Andrew Jackson in the White House – who enshrined parties in the political firmament. After Jackson won the popular vote in 1824 but was thwarted by the electoral college and the House, Van Buren went about cobbling together the coalition that paved the way for Jackson’s win in 1828.

Van Buren’s tool of choice was a reconstituted and singularly named Democratic Party, which helped him succeed Jackson in 1837. Tomasky stresses that American parties were traditionally coalitions that retained their viability through competing and often contradictory interests. In other words, parties were less ideologically consistent than they are today. FDR won the support of southern whites, northern blacks and urban ethnics, an amalgam of folks who might not have abided in each other’s company if stuck in the same room – except if that room were the floor a national political convention.

Before too long, the kind of car one drove, music one listened to, and salad greens one preferred were taken as indicators of political identification

Tomasky also chronicles the 1960s, the genesis of the Reagan coalition, and the cultural forces that have buffeted and transformed the national landscape. In Tomasky’s words, welcome to the “Age of Fracture”, an epoch that began in 1980 with Ronald Reagan’s election and that shows no end in sight.

Among other things, Tomasky captures the resistance of southern evangelicals to a civil rights movement driven by the Reverend Martin Luther King and aided by a now-dying mainline Protestantism.

“Preachers are not called to be politicians, but soul winners,” thundered the late Rev Jerry Falwell, that is until he founded the Moral Majority and white evangelicals made the party of Lincoln their home. Fittingly, Falwell’s son has morphed into a Trump-booster extraordinaire.

Tomasky also looks at the marriage of the bohemian ethos, market capitalism and hyper-individualism, and cites what 20 years ago David Brooks called “Bobos in Paradise”, AKA heaven for the few, purgatory for the many.

As Tomasky puts it, “before too long, the kind of car one drove, music one listened to, and salad greens one preferred were taken as indicators of political identification”.

Beyond that, “these choices were never equal in terms of the moral weight they purported to carry”.

Even before Barack Obama audibly lamented the white working class clinging to God and guns and Hillary Clinton slagged on the “irredeemably deplorable”, America’s super postcodes – places where high incomes were fused to similar levels of education – had hived off from the rest of us. Tomasky is astute enough to see where this led, and wise enough to understand the limitations of altering this trajectory.

As a corrective, he suggests student exchange programmes within the US, shortening college to three years and substituting year four with national service, and attempting to infuse school curriculums with a serious dollop of civics: all worthwhile endeavours that ultimately operate at the margins.

The challenge first posed by Benjamin Franklin at the close of the constitutional convention in 1789, and echoed by Tomasky, remains unanswered. Can we keep this republic?