Her climate change art is finally being recognised: Chilean artist Cecilia Vicuña and how the world finally caught up with her

- Vicuña created ‘land art’ before it became a movement; she was an eco-feminist before it became a term. Now, awareness of her work is steadily increasing

- This month, her art can be seen simultaneously in three Asian cities, including re-paintings she did of childhood artworks lost during Chile’s military coup

The black-and-white photo is dated 1966. It shows a girl aged 17, short-haired, square of jaw, drawing emphatic spirals on a beach in Chile with a large stick. Her creation, like the smaller sticks she places on the shoreline exactly where they’ll be washed away, won’t last. She doesn’t care.

Her name is Cecilia Vicuña. She’s certain that the sea is aware, the wind is aware, the light is aware and that she’s connected to all of them.

You, however, probably aren’t aware of Vicuña. Until recently – and she’s the first to say it – her recognition as an artist beyond Latin America has been limited. For more than half a century, she’s been honouring lost cultures, lost objects, lost glaciers, lost languages, lost people. In the process, she was almost lost too.

She created “land art” before it became a movement; she was an eco-feminist before it became a term. Those little sticks in the sand would evolve over decades into a body of work she called Los Precarios – a collection of fragile, transient offerings, made to disappear. But being a pioneer, especially a female one, can be a lonely business. When she held exhibitions about what wasn’t yet called climate change, few showed much interest.

Now the art world is catching up. In 2017, her solo exhibition, “About to Happen”, began a tour of the United States; the same year, she took part in an influential art exhibition called “Documenta”, which is held every five years in Germany.

Since then, international awareness of her work has steadily increased. In 2019, she was shortlisted for the Hugo Boss Prize; she was part of Tate Modern’s A Year in Art: 1973 in London; and her work was included in the permanent collection’s rehang at New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

This month, she can be seen simultaneously in three Asian cities: at the Shanghai Biennale in China, the Gwangju Biennale in South Korea and, for her first solo show in Asia, at Lehmann Maupin Seoul, also in South Korea.

Vicuña, now 73 and with a long braid down her back, has the infectious passion of someone who can’t wait to express delight at this turnaround. “I knew, I knew what I was doing was art and I knew it was different from Western culture. It wasn’t in the books,” she says via Zoom from New York. Her speaking voice is so softly melodic that it gives the interview a strange intimacy. (Some of her laments during her performance art can sound like an ancient croon from a history you didn’t know you’d shared.)

Stepping outside the mainstream had been a deliberate childhood choice. As with many Chileans, her family background is an intermingling of both European and indigenous blood (a DNA test has shown she’s half-Asian). When she was sent to Santiago’s St Gabriel’s English School aged nine, where she was bullied, she decided to claim only her indigenous side. As she puts it, “I decolonised myself.”

Maybe this self-division unsettled her; during her teenage years in Santiago, she wrote a poem about how her life was a failure. Even allowing for adolescent angst, it was a curious belief not least because, at the time, success seemed likely. After all, she’d been born – “at the foot of the Andes” – into an encouraging clan that included female artists, a grandfather who had been a lawyer for Nobel-prize-winner Pablo Neruda and a father who built her a studio at the bottom of the garden.

The family was friendly with Salvador Allende, who became president of Chile in 1970, the first democratically elected Marxist leader in South America. In 1971, when Vicuña heard the director of Chile’s National Museum of Fine Arts on television encouraging young people to exhibit in the museum, she ran – literally, past the secretaries – into his office.

By chance, he’d read her poetry in a Mexican magazine and, on that basis, gave her an entire room. She filled it with dying autumn leaves. Asked now why she’d focused on decay at a time of youthful political optimism, she says, simply, “Because everything dies. For me, you couldn’t effect a revolution of the mind unless you acknowledge death.”

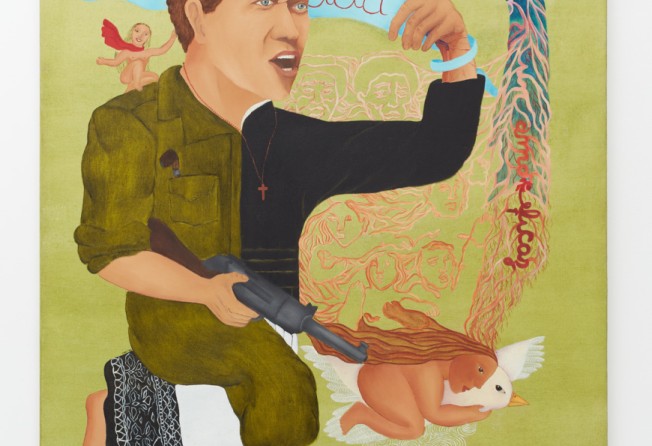

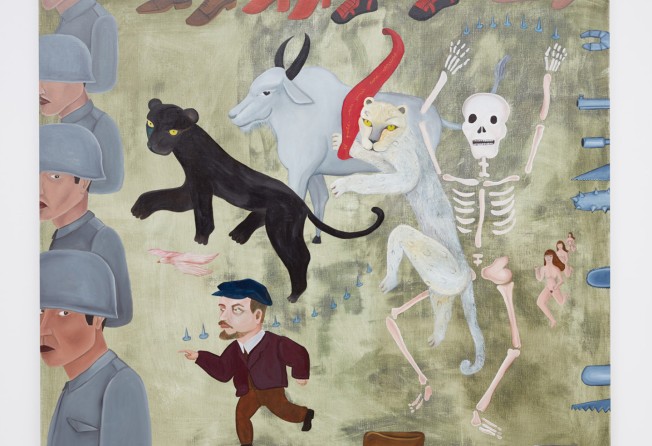

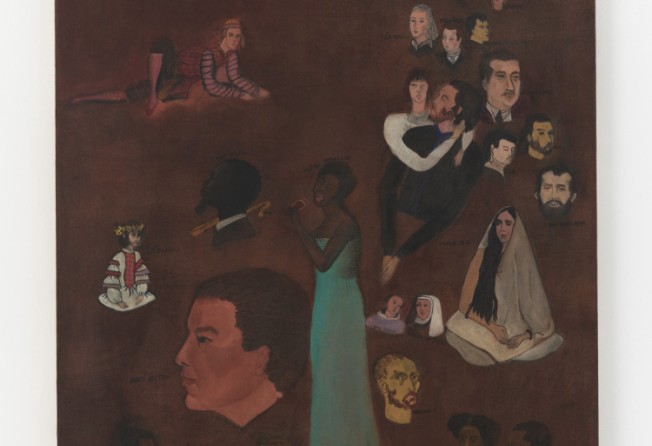

She painted portraits of Karl Marx, Vladimir Lenin, Fidel Castro (no, not Mao, she says, a little surprised at her own omission. Her grandfather was once invited to China to receive an award from the government for his political work). Her provocative style – she has described it as “clumsy, idiotic”, deliberately unschooled – was an act of rebellion against the Catholic Church’s colonial-era standards. She wanted to be “as not belonging as I could be”.

Then she travelled to London to study at the Slade School of Fine Art, which is where she was when Allende was overthrown by the military – and committed suicide – on September 11, 1973.

Much death ensued in Chile. For a year, she walked London’s streets, collecting found objects from which she made artistic offerings to honour those who were executed or “disappeared” under the reign of General Augusto Pinochet. In Chile, her own works vanished. “With this disaster, who was going to take care of the paintings of a young girl?” she says.

Although she continued painting, in Chile, no one cared. “I was incredibly poor in exile. I hardly got enough to eat. And for what? I didn’t stop. The painting stopped in me.”

Eventually, she settled in New York in 1980, married – and later divorced – an older Argentine artist, and toiled, mostly invisibly, on her art. For decades, she was better known as an activist and poet. In 2009, she co-edited The Oxford Book of Latin American Poetry.

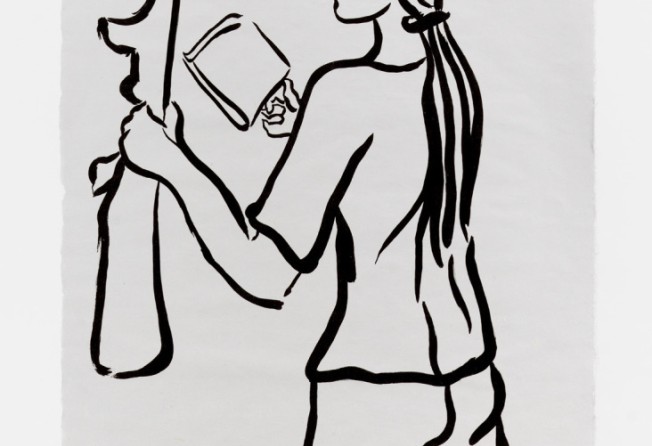

Her poetry and visual art had always been intimately connected: in the 1970s, she’d coined the term palabrarmas – literally “word weapons” – for her paintings of words on textiles. She continued to infuse her performance art with poetry. But not until 2013 did she pick up a paintbrush again, and what she painted were her own lost works.

Asked if this has been an attempt to recapture a departed world, the innocence of her own youth, she becomes emotional. “It makes me feel like crying because that’s the absolute truth,” she says. “And I have to say when Rachel Lehmann asked to see my paintings – that was something really new. It gave me confidence.”

Lehmann had seen Vicuña perform a poetry reading in Athens, in front of one of her quipu installations, as part of Documenta 14 (that year’s event was split between Germany and Greece). Quipu – knots tied at specific points along string that were used as a form of record-keeping in the pre-Columbian era – is something Vicuna learned about as a teenager, a visual gift from the past to a young woman seeking connections to her present.

“Her work stood out remarkably to me, more so than anything else,” Lehmann says via email. “I think poetry transcends everything Cecilia does. That’s what touched me … She brings a certain ancestral wisdom that she passes on in her work but she also has this free spirit that doesn’t correlate with her age. She is trying to connect the voices of the people over many generations.”

The re-paintings – Vicuña calls them “doubles” – will be present at all three Asian venues. Lehmann Maupin Seoul has also commissioned a quipu. Over the years, these massive swags of wool and thread have proved adaptable metaphors. They’ve been used to signify the threat to Chile’s glaciers and to honour the dead of California’s forest fires.

The Korean commission will be the first time Vicuña has actually painted on one. The Seoul gallery sent her textiles, including a hanbok, a traditional item of Korean clothing, which she combined with gauze and cotton to create large-scale columns. They appear transparent but contain her own hidden calligraphy, neither Korean nor pre-Columbian – a script that exists in between. “If you look at it, it’s like nothing,” she says. “But if you move, you see how the layering of realities begins to appear.”

Which sounds like Vicuña herself: an apparent blank for so long, whose complex layers are now on greater public view. Colonisation, memory, language, exile, political art, climate change – no wonder she’s touching a current nerve. The determined teenager on a long-ago Chilean beach is now connected to the geopolitical universe of curators, gallerists and biennales.

How does she feel about that landscape?

“Let me tell you, the First World is changing too,” she says, earnestly. “That interest in seeking the other mind is there. And why they are interested in me is – I am the other mind.”

Cecilia Vicuña’s solo show, “Quipu Girok (Knot Record)”, opens at Lehmann Maupin Seoul on February 18 and continues until April 24. The Gwangju Biennale begins on April 1 and continues until May 9. The Shanghai Biennale continues until June 27.