How Chinese porcelain went global: Hong Kong exhibition full of rare pieces puts creative spin on an old paradigm

- Early Chinese porcelain paired with copies of Western paintings featuring similar pieces is one feature of the Chinese University of Hong Kong art museum’s show

- It is one of a number of special projects marking the museum’s 50th anniversary, which also includes an exhibition about Guangdong artists and collectors

Some of the exhibits at a new show about Chinese trade porcelains are not what most people would think of as “museum quality”.

But these chipped plates, water-damaged teapots and humble fragments of Chinese blue-and-whites are being shown alongside magnificent and rare pieces that have survived intact at the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) art museum to put a new spin on a well-known paradigm of globalisation.

The history of the West’s obsession with Chinese porcelain is well known. In the 16th century, enterprising European merchants began supplying their home markets with Chinese porcelains made with Western consumers in mind, and they sold so well that a great trade imbalance developed.

That began to change in the 17th century, when wars and periodic maritime trade bans during the Ming dynasty disrupted supplies from the Jingdezhen kilns in China’s southeast, resulting in Japan becoming the biggest exporter of porcelain. But what really broke China’s dominance forever was a failed experiment by a German alchemist in 1709 that resulted in Europe’s first hard-paste porcelain able to match Chinese porcelain in quality.

“Enchanting Expeditions”, an exhibition that is part of the CUHK art museum’s golden jubilee celebration, is an engaging account of how porcelains moved around the world.

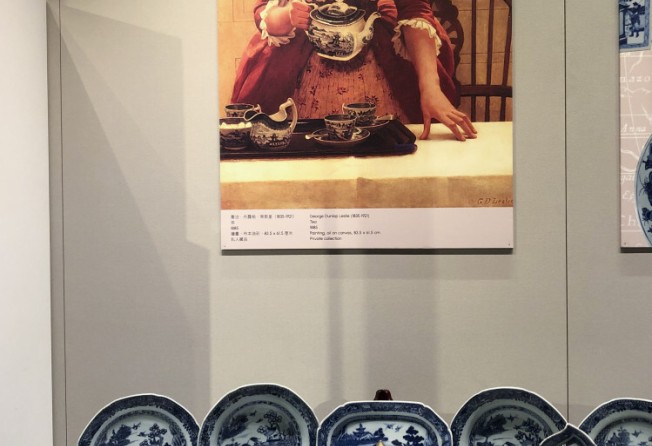

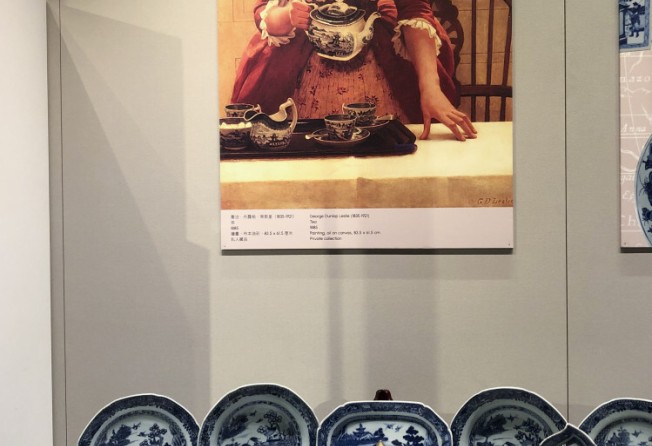

This is highlighted particularly effectively through the pairing of objects with copies of Western paintings that feature very similar pieces.

For example, a Victorian maidservant in a painting called Tea (1885) by British painter George Dunlop Leslie is seen with a blue-and-white Chinese-style tea set that has near-identical patterns to the Qing dynasty (18th century) dinner service that Hong Kong collector Anthony Cheung Kee-wee recently donated to the museum.

An enduring fashion for Chinoiserie meant that there was a steady trade for made-in-China ceramics decorated with Christian motifs, coats of arms, Western figures or cliched Chinese symbols.

Often, blank porcelains were shipped to Europe and then decorated with overglaze painting, such as an 18th-century cup and saucer set depicting the crucifixion of Jesus Christ that was fired in the Netherlands. But mostly, the pieces were made in Jingdezhen, the porcelain capital of China, which exported everything from punchbowls bound for England to communion plates ordered by the Portuguese.

Many of those pieces didn’t make it to their intended destinations. The exhibition includes pieces salvaged from seven shipwrecks that became time capsules revealing the main types of porcelains that were being sent to different overseas markets, including those in Asia and the Middle East.

Meanwhile, generations of Western craftsmen tried to reverse-engineer the imports that were more translucent and white than their so-called soft-paste ceramics that were fired in lower temperatures. Some looked quite similar to the Chinese originals.

For example, there’s a photograph in the exhibition of a 16th-century vase with a deer and crane pattern from the Louvre Museum that was made in Florence under the patronage of Francesco I de’ Medici, the second Grand Duke of Tuscany.

It was most probably a copy of a Ming dynasty bottle made for a Portuguese merchant with the exact same motifs that is on show here, on loan from Cheung’s Huaihaitang collection.

Eventually, Johann Friedrich Böttger would discover the secret to making Chinese style porcelain and helped set up the Meissen porcelain plant in Germany in 1710, which was followed later by other successful European centres such as Sèvres in France, Delft in the Netherlands and Worcester in England. There are examples from those factories on show, too.

The exhibition is one of a number of special projects marking the 50th anniversary of the CUHK museum, which also includes a concurrent exhibition about Guangdong artists and collectors starting from the 17th century.

Over 70 examples of paintings and calligraphy show how the area near Hong Kong was already thriving with culture – albeit with its own regional characteristics – during a time when it was dismissed as a cultural desert.

“Enchanting Expeditions” (until January 2) and “Artistic Confluence in Guangdong” (until November 28), Art Museum, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Sha Tin, Mon-Sat (closed on Thurs), 10am-5pm, Sun 1-5pm.