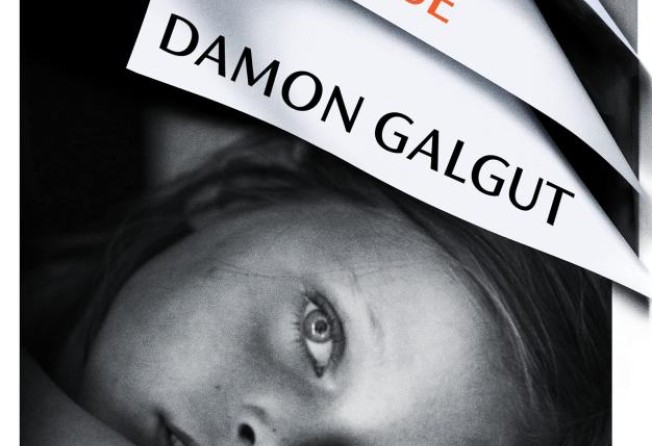

Damon Galgut’s Booker Prize-winning The Promise, about the downfall of a white South African family, is a novel of mesmerising skill

- Galgut’s ninth novel, and the third to make the Booker Prize shortlist, charts the downfall of a white South African family, starting in the apartheid era

- The narrative passes from character to character, creating a beguilingly chaotic relay of voices that tell a story of injustice stretching over 30 years

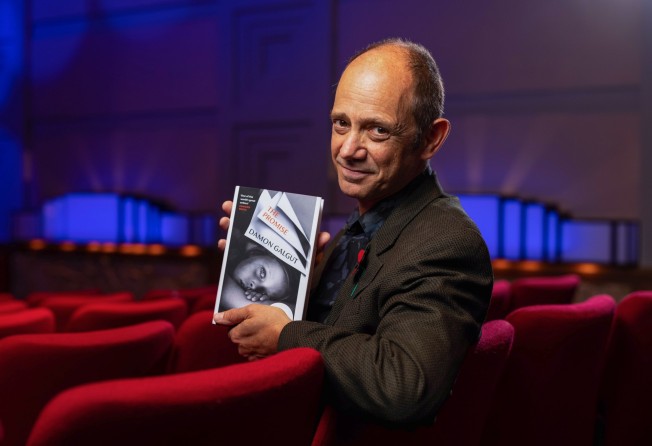

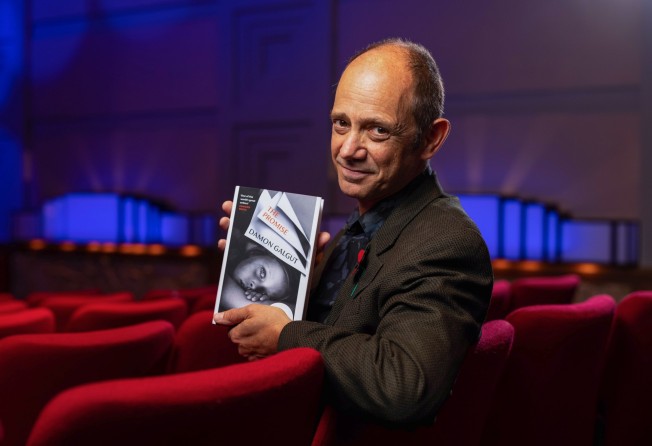

The Promise by Damon Galgut, pub. Chatto & Windus

Damon Galgut has won the 2021 Booker Prize for the best English-language novel published in Great Britain. His remarkable and brilliant novel The Promise tracks the downfall of a white South African family over 30 years, set against South African history from the last years of apartheid.

The Promise is Galgut’s ninth novel, and his third to have been shortlisted for the £50,000 (HK$533,000) prize since his first work was published when he was 17. (Galgut has previously said that his love of books stemmed from relatives reading to him during his treatment for lymphoma as a child.)

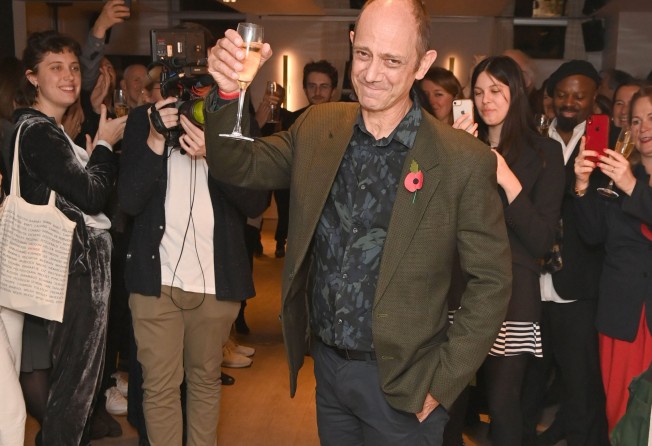

Accepting the prize, Galgut said: “Let me say this has been a great year for African writing, and I’d like to accept this on behalf of all the stories told and untold, the writers heard and unheard, from the remarkable continent I’m part of. Please keep listening to us, there’s a lot more to come.”

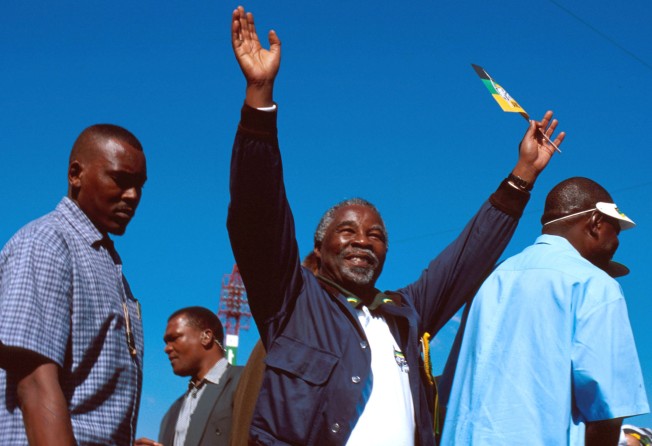

The Promise is in four sections, named for four of five Swart family members, Ma (Rachel), Pa (Manie), Astrid and Anton, each paralleling moments in South African history: President P.W. Botha’s state of emergency in the mid-1980s; President Mandela at the 1995 Rugby World Cup; the 1999 inauguration of Thabo Mbeki as president, and the resignation of Jacob Zuma as head of state in 2018.

Through this structure we observe the end of apartheid and its reverberations in violence, the HIV/Aids epidemic and continued dispossession of the majority black population. The 30-year deferred promise of the title is that the Swart family will give their servant Salome ownership of the house she lives in.

Galgut’s book is most virtuosic in its shifting, multi-perspectival narration and its intense, surprising sentences. Narration is passed from character to character with mesmerising literary skill, creating a dexterous and beguilingly chaotic relay of voices and thoughts.

The family story is built up around Rachel (like the mother in William Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying). Ill with cancer – Rachel dies as the book opens – she had been cared for by Salome, and promises Salome the house that she and her son Lukas occupy, makes her husband swear to keep her promise – which is overheard by their third child, 13-year-old Amor, the only family member who does not try to forget.

In her illness, Rachel found her way back to Judaism and – in this book of four funerals – her written insistence on a Jewish burial causes conflict and resentment in her Dutch Reform in-laws (and sets the pattern of a faith per funeral).

The Promise is also remarkable in its depictions of the movement of time for individuals and nations. Time passes, but it doesn’t flow evenly:

Look at this, [the children’s uncle] exclaims. Jirre hey. My goodness.

His tone is jocular and astonished, at how much his nephew has changed. But he himself has become an emphysemic husk of what he used to be. And all of them are different, of course they are, time has played its tune on all our faces.

Or as the nameless, homeless man the narrator arbitrarily calls Bob puts it:

Time passes differently for those who’re shut out of the world. It travels past like traffic at certain points in the day, or like a particular shadow inching across the ground, or like your own body, signalling its cravings to you.

The nation, too, is changed in life and in death. As Anton goes to visit his dying father, he pauses:

A new, democratic government in the Union Buildings! […] Wonder if Mandela is in there right now, at his desk. From a cell to a throne, never thought I’d see in my lifetime. Weird how quickly it’s come to seem ordinary.

And on Manie, comatose and stupidly dying from snakebite beside “a black man in the next bed, bandaged up like a mummy” in Pretoria’s H.F. Verwoerd Hospital (named for the prime minister regarded as apartheid’s designer):

Apartheid has fallen, see, we die right next to each other now [ …] It’s just the living part we still have to work out.

Two of the children, Anton and Amor, rebel against family and nation. Anton abandons his military conscription, follows a self-destructive, alcohol-afflicted route, and is disowned by Manie for speaking his mind to his father’s charlatan minister. Amor leaves South Africa for London, though the pull of family – and, uniquely, the promise – persists. Only the third sibling, Astrid, materialistic and vain, keeps contact with the others.

As for South Africa’s prospects for justice, “Oh, dear me, [Anton says to Amor after Rachel’s funeral]. Do you have no idea what country you are living in?”

Some may know. When Pa’s funeral approaches, and there is real work to do, “The two whites get into their car and drive away, the two blacks go on digging.”

Salome doesn’t get to narrate. Through it all, only she, waiting for justice, remains silent.

Damon Galgut appears at the Hong Kong International Literary Festival, in conversation with Xiaolu Guo, at a hybrid event on Nov 11, 7-8pm. Visit festival.org.hk for details.