Why East Germany’s much-feared Stasi secret police studied poetry

- Officers of the ‘Circle of Writing Chekists’ within the Stasi discussed poetry to better detect literary subversion, at a time when art was seen as a weapon

- ‘The Stasi Poetry Circle’ by Philip Oltermann provides a surprising, entertaining and enlightening account of the role of poetry in state control

In pre-reunification Berlin, a handful of officers from East Germany’s much-feared secret police, the Staatssicherheitsdienst or Stasi, and workers in their private compound, would regularly sit down in a specially reserved conference room to discuss not police work, nor politics, but poetry.

This “Circle of Writing Chekists” sometimes studied the 14-line sonnet and how its form of thesis, antithesis and synthesis supposedly reflected Marxist dialectical materialism and the style of “debate” common to communist states.

Sometimes they discussed the verse structure of the 19-line villanelle, and sometimes the threat posed by metaphor. They read out their own poems, and intermittently published collections of verse.

“Cheka” was the Lenin-era name for what would go on to become the USSR’s KGB, and then modern Russia’s FSB. The East German version, the Stasi, more commonly discussed feet in terms of using them to kick down doors, not as units of stressed and unstressed syllables in poetry.

But in a country where the written word was seen as a cultural unifying force of considerable power, and where circles of writing workers were being set up in factories and organisations of all kinds, the Stasi must be able to understand the literary tools available to the forces of dissent: allegories, metaphors, fables and alienation effects.

It was finding one of the circle’s red-jacketed volumes that led The Guardian’s bicultural Berlin bureau chief, Philip Oltermann, to immerse himself in Stasi records, to read the reports the circle’s members made on each other, to sift through poems published and unpublished, and to track down some surviving group members to make its story scan.

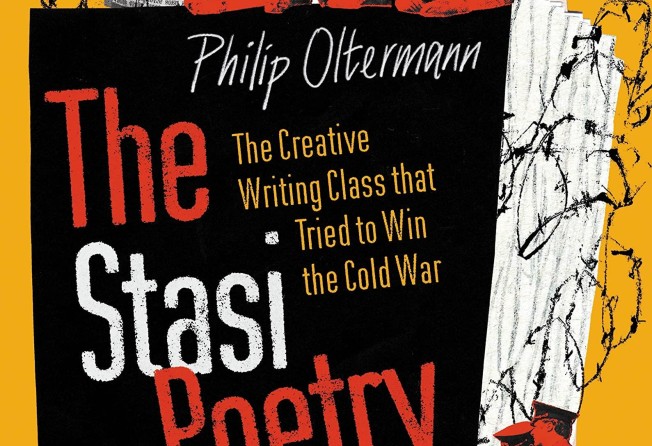

The result is The Stasi Poetry Circle – The Creative Writing Class that Tried to Win the Cold War (published by Faber & Faber), a surprising, entertaining and enlightening account of the role of poetry in state control, and of the determination of Germany’s Socialist Unity Party dictatorship, complete with Five Year Plan, to surpass the West in the volume of its literary achievements.

But there’s more than a little of Monty Python in Oltermann’s description of secret policemen having po-faced discussions of the poetic.

“I think when I first got hold of this anthology of poetry I found it quite hard to find a way into it,” says Oltermann via video chat from Berlin. “But the poems that I did find meaningful were the ones that were comical but sometimes not deliberately so, such as the poem where a Stasi man tried to talk about concepts like love in terms of ownership. He wants a woman just for himself, and he doesn’t want her to be nationalised or collectivised.”

Literature might be a more effective medium than speeches or diktats to convey pro-socialist and pro-Party messages especially to the more educated classes. Art was seen as a weapon.

Class barriers between the cultured and the rest must be broken down, and there was no reason why a worker could not be a critic, and vice versa. “Pick up the quill, comrade!” was the slogan, and writers were sent to work in factories and to organise circles of writing workers, while, of course, reporting on what they heard.

Underlying all this was the standard Stalinist line that the purpose of art should be to promote socialism. Good verse was simple, clear and unambiguously pro-Party. But this could be problematic in terms of writing well.

If a poem contained an image of a plane in the sky and a vapour trail behind it, this would not be a simile, but merely a comment on technological achievement.

“In many ways it goes against the whole idea of what poetry does,” Oltermann says. “Poetry deals not just with surfaces but with ideas and emotions that lie underneath the surface, and when it comes to the practice of writing poetry, the idea that things should be on the surface seems to be completely at odds certainly with what my understanding of poetry was beforehand.”

The Stasi, proudly proletarian, didn’t want smart alecs, he says.

“It didn’t want to have people who were good at writing; it wanted to have people who got things done. So it hadn’t placed that much value in academic learning. But it also felt that something was building up that it couldn’t quite understand.”

And this fear of missing the point, of ambiguity, of language that might seem to say one thing while actually saying another, led to the Stasi’s increasingly detailed study of literature, to enable it to better detect literary subversion.

Ordinary people equally learned to read more closely. East Germans, Oltermann writes, “excelled at working out not just what a text said on the surface, but what it said between the lines, irrespective of whether that text was a poem by Goethe, a newspaper article on the opening of a new chemical plant, or The Communist Manifesto.”

He tells how the Stasi tracked down and persecuted one young woman whose handwritten lines were found in the possession of a schoolgirl.

“These weren’t poems written by a powerful, influential author admired by millions, but an unemployed 21-year-old with no publishing contract to her name. They weren’t photocopied verses going viral behind closed doors, but lines handwritten into a school notebook, shared with no more than five close friends.

“How could a state be so scared of a few lines of verse?” he asks.

What made them threatening was not what they said, but that it was unclear whether they said anything at all.