Hong Kong Ballet and Philharmonic’s ‘Carmina Burana’ double bill suffers from stark mismatch

- Ricky Hu’s hauntingly beautiful piece ‘The Last Song’ was in sharp contrast to ballet director Septime Webre’s ill-judged take on Carl Orff’s ‘Carmina Burana’

- The philharmonic deserves full credit for doing justice to two such different composers, while the ballet’s dancers were superb

Titled simply “Carmina Burana”, the new joint production by the Hong Kong Ballet and the Hong Kong Philharmonic featured a version of the title piece by Carl Orff created by the ballet’s artistic director, Septime Webre, originally written in 2016 for the Washington Ballet.

The production also featured The Last Song, a new work set to Bach by choreographer-in-residence Ricky Hu Songwei.

This was a mismatched double bill. While conductor Lio Kuokman and the philharmonic deserve full credit for doing justice to two such different composers, Hu’s elegant, hauntingly beautiful dance piece was in sharp contrast to Webre’s ill-judged, overblown take on Orff.

The Last Song is inspired by Oscar Wilde’s “The Nightingale and the Rose”, one of the most unbearably poignant stories from Wilde’s The Happy Prince and Other Tales.

In the story, the nightingale kills herself in an act of selfless love for what turns out to be a worthless cause – a theme prophetic for Wilde himself, whose passion for poet Alfred Douglas would lead to his destruction.

Hu has not adapted the story directly but has chosen an abstract treatment that explores the relationship – sometimes joyous, sometimes stormy – between an artist and his muse, symbolised by the nightingale.

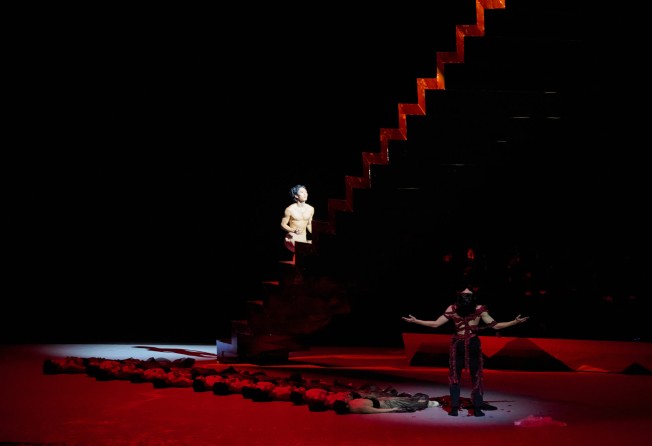

The two leads were supported by a 16-person corps de ballet in the role of the roses, which represented the ceaseless quest for perfect beauty and pure love, while the music was played on stage by a chamber ensemble from the orchestra.

At first the costumes designed by Hu and Joanne Chong seemed surprisingly sombre. It was only at the end, when the artist was bound in chains of red, no longer able to move, that colour flooded in to evoke the heart’s blood of the nightingale’s sacrifice.

This final image, with the nightingale ascending at last to a plane where beauty and love may, perhaps, exist, had tremendous power.

It is several years since we saw Hu’s work in Hong Kong and The Last Song shows how complete a mastery of his art he has developed since then.

The piece is well-structured and the choreography is consistently original and exceptionally musical, whether in the deeply felt solos and duets for the two leads or the inventive, intelligent use of the corps.

An intricate lift in the first encounter between artist and muse, done twice – first with one dancer supporting, then the other – was not only breathtaking technically but perfectly encapsulated the bond between the two.

Both casts in the lead roles – Kyle Lin Chang-yuan as the nightingale with Luis Cabrera as the artist, then Yonen Takano with Leung Chun-long – were superb, matching each other in dramatic intensity while bringing their own nuances to the roles, with Takano creating a particularly vivid birdlike quality.

Carmina Burana, composed by Orff in 1936, is a popular (indeed, populist) work that some people dismiss as vulgar and bombastic, while others enjoy its drama, huge choruses and intriguing medieval libretto.

Like all choral works, it achieves its full impact performed live and here was sung splendidly by the Hong Kong Philharmonic Chorus, with excellent solo work from tenor Ren Shengzhi, soprano Vivian Yau and baritone Elliot Madore. The baritone had the most to do and Madore’s strong stage presence matched his lively singing.

The performance was a feast for the ears, but not so much for the eyes.

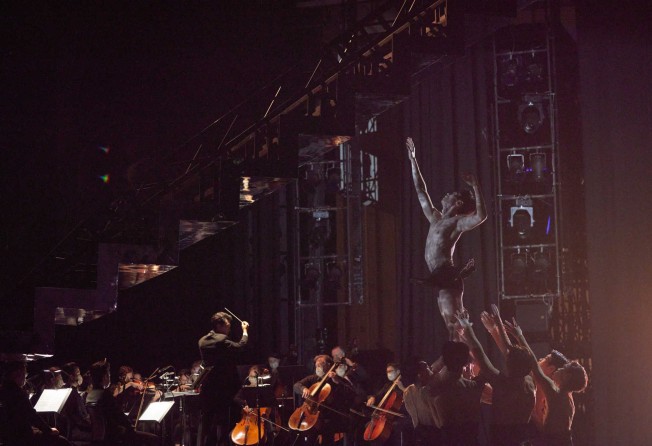

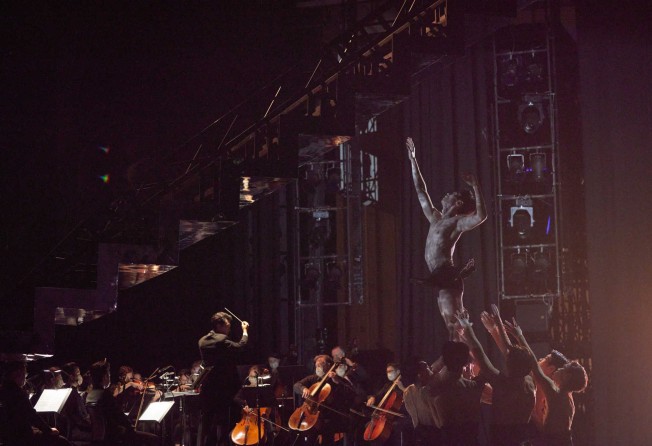

Webre is always a showman; his ingenious set design of three-storey-high scaffolding evoking monks’ cells to house the chorus was spectacular and his trademark high energy and penchant for theatrical effects were on display.

However, his choreography fails to respond adequately to the score – indeed on the first night it seemed completely disconnected from the music and simply didn’t gel.

The second show was more cohesive but the choreography lacked originality and suffered from Webre’s habit of throwing technique at everything, whether those steps fit the music or not.

In terms of the dance, the best section was the effective use of stillness and slow-motion movement in “Dies, Nox et Omnia”, followed by a charming duet to “Stetit Puella”, beautifully danced by Jonathan Spigner and Kim Eunsil in the first cast, Takano and Nana Sakai in the second. This was a classic example of less is more – a dictum Webre seems reluctant to embrace.

The libretto was selected from a 13th-century manuscript which, although discovered in a monastery, deals with strictly secular themes – the swings of fortune, the pleasures of the flesh. It gives fascinating glimpses into how ordinary people thought and felt in medieval times.

Instead of exploring this, Webre has chosen to incorporate references to Virginia Woolf’s Orlando. This whimsical, sophisticated satire about a young man in the 1500s who mysteriously turns into a woman and retains eternal youth for centuries is the antithesis of Carmina Burana’s earthy text and Orff’s dramatic music. It’s baffling to see why anyone would come up with the idea of putting them together.

A sequence of comic scenes involving pantomime-style figures with two-metre-high crinolines (female dancers sitting on the shoulders of male partners hidden by their skirts), followed by numbers for men with brooms and women in Elizabethan drag, lacked Webre’s usual flair for comedy and conflicts with the style, tone and feeling of the music.

Liz Vandal’s costumes, intended to reflect the successive eras of Orlando’s life, also clashed with the music – 18th-century frills and Edwardian furbelows simply don’t go with Orff’s complex rhythms and stark instrumentation, while the opening medieval sequence had the dancers in flapping grey rags that looked like something out of a 1950s B horror movie.

A number of scenes featured flesh-coloured leotards presumably meant to evoke nudity, which made the dancers look disturbingly like store-window dummies: naked but no naughty bits.

The company’s dancers gave their all (albeit, like Wilde’s nightingale, for an unworthy cause). The second show was lifted by outstanding performances from Jessica Burrows, dancing with style and passion, the sparkling Sakai, and Cabrera, whose fluidity and expressiveness of movement transcended technique to infuse his solos with some real emotion.

“HK Ballet X HK Phil: Carmina Burana”, Hong Kong Cultural Centre Grand Theatre. Reviewed: October 14 (evening) and October 15 (matinee).