Artist inspired by Occupy joins Sham Shui Po market fight

Angela Su recently led fashion models and textile vendors on a protest march. It was new territory for a woman whose art has often been confrontational but rarely collaborative

It is the Sunday after Christmas and a surreal scene is unfolding in the heart of Sham Shui Po.

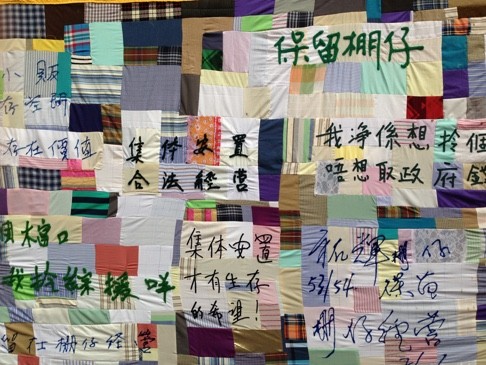

Models wearing elaborate couture strut through the streets, accompanied by a ragtag band of musicians sounding like they are straight out of New Orleans. Following closely are a group of mostly silver-haired protesters waving banners with phrases such as “I want to buy cheap cloth”.

This is a mobile fashion show in support of the rabbit warren that is Hong Kong’s most atmospheric fabric and accessories market.

The 38-year-old Yen Chow Street Hawker Bazaar is probably the only place in the city where someone experimenting with a design idea can ask for half a yard of tweed without being spat at. But the government says it is a health-and-safety nightmare and needs to come down. The stallholders – the ones with the banners – fear they will have nowhere to go.

It isn’t easy steering the crowd along the circuitous route from Tai Nam Street to Yen Chow Street while allowing for frequent pauses when the models dance and pose. But first-time activist Angela Su is unfazed. Dressed in her signature combination of black goth and retro, oversized glasses, the Hong Kong artist makes an efficient master of ceremonies as she and fellow organisers move the show along.

On my own, my voice is limited. I’ll need to juggle these different [collaborative] projects. If it’s too ‘arty’ it doesn’t say things clearly. If it’s too direct, it’s not art

“Sham Shui Po is an old and low-income neighbourhood. It is also very real. Unlike the rest of Hong Kong, it hasn’t been overrun by shopping malls and the same chain stores. Sham Shui Po has its own way of survival,” she says, explaining her decision to get involved.

Hong Kong artists have a long tradition of social or political involvement and in recent years, they have certainly become more active just as the whole population has become more engaged.

Even before 2014’s Occupy Central protest, which saw a flowering of creativity on the streets, artists had taken part in protests against efforts to pass a law against sedition, secession, treason and subversion as required under Article 23 of Hong Kong’s Basic Law (2003), hung banners off the Museum of Art to condemn Beijing’s treatment of dissident artist Ai Weiwei (2011), and showed up in the annual July 1 anti-government marches as a contingent.

Still, Su cuts an unlikely figure among the more seasoned protesters in the art community. While artists such as Kacey Wong, South Ho and Wen Yau have incorporated local politics into their work, one of the defining aspects of Su’s oeuvre is its universal nature, its ethnic and national anonymity.

If transgressive art is a form of protest, however, then Su has been protesting for years. Mainstream attitudes to sex, gender, pain and to divisions between organic and inorganic matter are subjects with which she mercilessly confronts audiences.

Her works are always unsettling. In Berty We Trust! (held at Gallery Exit) from 2013 presented a gothic fantasy of torture machines melded with human organs and a cross-section of a torso, with arms outstretched, surrendering to the will of Su’s exquisitely drawn systems of wheels, levers, and pulleys.

With degrees in biochemistry and visual arts, she has mastered the craft of combining her two loves in the form of faux-Victorian scientific illustrations that often have a biomorphic element. She has produced different variations of Frankensteinian images in her ink drawings, hair embroideries and animations over the years.

“Through her analytical, medical drawing, she is able to express a dispassionate quality of observation, but her works also embody things within herself. So they are actually very passionate. This dichotomy is one of the reasons I’m attracted to her work,” says Valerie Doran, curator and art writer.

Performance art, in which the main subject is her own body, has also been an important channel for her. In 2012, prompted by Doran’s research into the treatment of pain in medical sciences and the humanities, the curator invited Su to have a series of discussions with cultural historian Sander L. Gilman about body integrity identity disorder (a desire for amputation), body modifications and self-harm. The result was The Hartford Girl and Other Stories, a video in which Su reads out fragments of texts on the subject of pain and the story of how a young American woman in distress had cut herself outside a church, in a town called Hartford, while a large crowd looked on, hooting and cheering.

Meanwhile, the camera focused on Su’s bare back as a tattoo artist inscribed 39 lines of texts from prayers without using ink. What’s left is a map of red, swollen words resembling the raw marks of flagellation.

It was one of the most powerful works of art by a local contemporary artist and a thoughtful, visual essay on the relationship between pain, redemption and pleasure.

That was not the first time Su showed she was willing to suffer for her art. For the 2013 edition of Art Basel Hong Kong, she arranged for male actors to stub out a cigarette on her arm, slap her and pretend to rape her along the Central waterfront.

In 2008, she wanted to work for a day as a freelance sex worker, though she abandoned the plan after four sex workers were murdered that same month. It was part of a residency programme that aimed to immerse a group of artists in Sham Shui Po, now one of her favourite districts in Hong Kong.

“Of course there is a limit to what I’m willing to do. I am frightened of pain, actually, and a whole lot of other things. I’d never jump off a building. But art gives me the excuse to try different things. If the concept is worth it, I’ll do it,” she says.

Artistic inspiration comes in the form of a long line of performance artists who have shocked audiences with their antics since the 1960s: from the feminist art of Carolee Schneemann and Marina Abramovic to Bob Flanagan’s on-camera acts of self-torture.

She’s seen how their works have been reduced to sensationalised headlines over the years, and she fears the same being done to hers.

“It’s not a competition to try and see who is more shocking. After all, there isn’t much out there that hasn’t been attempted before,” she says.

The reason for doing what she does is to earn the right to speak on certain issues.

“I don’t want to be someone who expresses my thoughts on something that I don’t know anything about. I do feel that you only have the right to talk about something if you’ve experienced it yourself,” she says.

I’ll need to juggle these different projects. If it’s too ‘arty’ it doesn’t say things clearly. If it’s too direct, it’s not art

What’s changed recently is a new desire to speak out about Hong Kong issues, and not just through her own art. She says Occupy Central changed her, stirring a need to take direct action and to work with other people who feel strongly about the same causes. After the Sham Shui Po fashion show, Su wants to publish an anthology of science fiction stories about Hong Kong in the future. “I’ve secured a sponsor and identified the writers. It’s a chance for us to ask the question, ‘what if?’, about Hong Kong,” she says.

Working with other people is new for her. “Artists tend to be very self-focused. But on my own, my voice is limited. I’ll need to juggle these different projects. If it’s too ‘arty’ it doesn’t say things clearly. If it’s too direct, it’s not art,” she laments.