Hong Kong's Wucius Wong delivers riposte to 'derivative' Chinese contemporary artists

The 79-year-old rejects the view of contemporary Chinese art on display in current M+ Museum exhibition, and says his own show of ink paintings at PolyU is free of the cultural cliches international audiences have come to expect from Chinese artists

Wucius Wong has been part of Hong Kong’s artistic establishment for so long, it’s easy to assume that an upcoming retrospective of the Chinese ink painter is just another nice tribute to a long and prolific career.

Not so. Wong, who turns 80 later this year, says “Ink Innovations and Crossovers”, which opens at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University on March 15, is his way of balancing what he considers to be a misguided view of contemporary Chinese art that is currently presented in a major exhibition organised by M+. The exhibition he refers to is a look back at the past four decades of Chinese art through the sizeable collection that Uli Sigg has donated to M+.

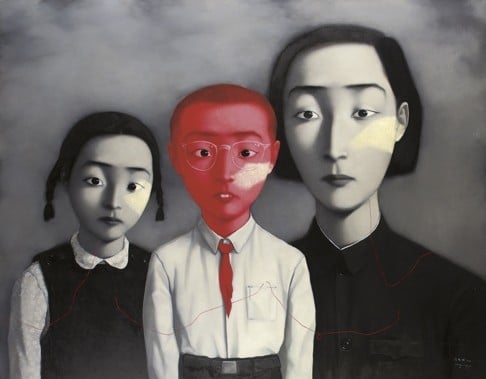

“So Zhang Xiaogang has painted a few people sitting in a row and that’s a masterpiece? So Yue Minjun’s character with the big smile is a new classic? I don’t think so.”

The otherwise genial Wong is quite forceful when it comes to what he feels are overrated “derivatives” of Western art.

Zhang and Yue are only representative of one particular generation whose emergence in the 1990s coincided with the international market’s newfound interest in contemporary Chinese art. These artists’ success and their enthusiastic adoption of what some critics say are accessible cultural clichés have often made them whipping boys in the current backlash against political pop and cynical realism.

Wong is not the first to say that this particular facet of contemporary Chinese art is overrated and overpriced, but his reaction is unusually strong for Hong Kong, where the mainstream art world does more or less accept that the post-1989 artists played a considerable role in the development of the genre.

The source of Wong’s contempt is part personal and part pragmatic.

As a young man in British colonial Hong Kong, Wong’s first artistic allegiance was to traditional Chinese culture. He founded a literary magazine and studied painting with Lui Shou-kwan, one of the most important pioneers of modern Chinese ink art. That cultural loyalty is inseparable from a patriotism borne out of his experience during the second world war.

I have seen the struggles of China from afar – from Hong Kong or the US – but I never forget my closeness to China and its culture. I want China to stand up again

“I have seen China go through tumultuous times. I remember Japan’s invasion during the war. I remember homes being destroyed, the country nearly destroyed. Over many years, I have seen the struggles of China from afar – from Hong Kong or the US – but I never forget my closeness to China and its culture. I want China to stand up again,” he says.

Part of that “standing up” is in pursuing cultural accomplishments that do not involve being absorbed by Western civilisation, he says.

And that’s something that people in Hong Kong have had a lot of experience of. “This soil suits the crossing of borders. Here, you cannot do anything that is ever purely Chinese or purely Western. It’s the same with my paintings,” he says.

His arguments are self-serving, since his works are very obviously from the Chinese ink tradition. But his views are honed not from a blindly ethnocentric world view, but a thoroughly cosmopolitan one.

In the 1960s, Wong left Hong Kong for the US, where he attended art school in Ohio and Baltimore for four years, finishing with a Master of Fine Arts degree from the Maryland Institute of Art.

“When I arrived there in 1961, abstract expressionism was all the rage, followed by pop art and minimalism. I was exposed to all that, attending lectures by the likes of David Smith and going to lots of exhibitions in New York,” the artist recalls.

I’ve always experimented with different styles. I also use oil as well as ink. I’ve never been against trying new things, and crossing boundaries

“I also received a good grounding in modern design concepts and ended up teaching design at the then Hong Kong Polytechnic when I came back to Hong Kong.”

He set up one of Hong Kong’s first design courses, and wrote books including Principles of Two-Dimensional Design and Principles of Color Design.

He designed a logo for the new exhibition that is a blend of modern design and Chinese calligraphy.

“I’ve used the shape of ‘wui’, the Chinese character for return. There are three meanings: return to China, return from immigration and return home – this is what many people in Hong Kong have been through.”

Wong taught design for 10 years at PolyU, the longest full-time job he’s ever held, before moving back to the US in 1984.

“Going to the PolyU is like going home for me. When I taught there, I was in my prime,” he says.

The exhibition will feature 32 works that represent different styles he has used in his works, from the abstract portrayal of water that is geometric in form, to sweeping, realistic landscapes that employ Western techniques of dealing with luminosity that he says are inspired by Baroque artists and Turner.

“I’ve always experimented with different styles. I also use oil as well as ink. I’ve never been against trying new things, and crossing boundaries,” he says.

The upcoming solo show is part of Wong’s commitment as artist-in-residence by invitation of the PolyU’s culture promotion committee, which has also arranged a series of talks and other activities around it.

“Ink Innovations and Crossovers: Retrospective Exhibition of Paintings by Wucius Wong”, Innovation Gallery, Podium, Jockey Club Innovation Tower, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, 11 Yuk Choi Road, Hung Hom. Mon-Sat, 10am-7pm. March 15 to April 24