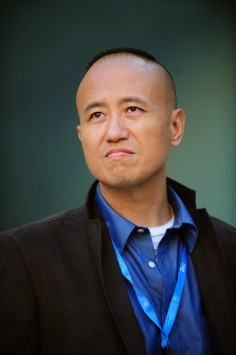

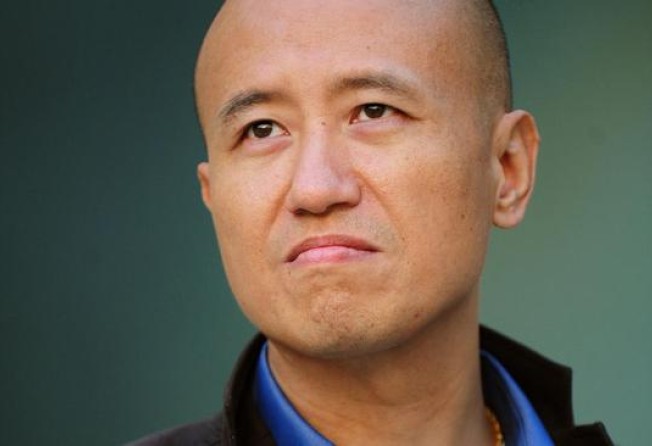

Oblique critiques of China's moral decay still relevant: Q&A with author Zhu Wen

When were the stories in your newly translated short story collection first written?

This book is a re-edited version. I wrote the stories 15 or, at earliest, 20 years ago. At the time of writing I believed they could stand the test of time. After 20 years there are still people reading them.

Much of your writing focuses on money and sex. Why?

In the past 30 years, especially since the 1990s, money and sex have become better examples to reflect a lot of societal issues or mentalities of society during China's rapid development. The attitude towards money is quite interesting; in the past China didn't have money. But as it gradually starts to have money, it lacks the education that comes with money.

In your newly translated short story , the sex-obsessed anti-hero is horrified when he is called back by authorities for political re-education 10 years after he graduated during the 1989 pro-democracy protests. You were also a student in 1989. Why did you decide to write about this period?

"Re-education" is a key phrase in China and it carries a strong political colour. It addresses the intellectuals who were "sent down to the village, up to the mountain" [during the Cultural Revolution]. I graduated from university in 1989. This year was a very important turning point in China. When this short story was published, it played the rules of the game, which is to make something sensitive more surreal. It's actually a political story, but because we can't talk about politics, we might as well talk about something else made up.

You studied engineering at university before working in a thermal power plant for half a decade. Why did you decide to become a writer?

If I were asked this in different times, I would probably give different answers. The basic attitude I have is that I never really intended to become a professional writer even when I was just starting out. First of all, I think writing itself is a process of finding that answer as to what I really want to do. Secondly, I was pursuing something of pure enjoyment. I was very chilled out and relaxed about the concept of writing.

In 1998 you and other writers spearheaded the "Rupture" movement, which preached a break away from official literary institutions. What did you want to achieve?

We wanted to break away from the old system, which confines writers. For example, there is this Chinese Writers' Association that recognises you as long as you agree to certain terms.

Your books seem to be critiques of decaying morals following China's opening up and reform.

I think my books are about my generation reflecting on Chinese culture and criticising it. This culture was created to centre around communism, and the party doesn't really reflect the people. A lot of traditions have been lost, a lot of Chinese values have been lost.

You were born in 1967 during the Cultural Revolution. How do you look back on those years?

The Cultural Revolution was a disaster. For some people it was tragic, for others it was like a carnival.

Is any of your work autobiographical?

No. Of course you can trace some of my footprints in my books, but [they're not platforms] for my ideas and thoughts. I think if I wanted to express those I would have just written an opinion piece and taken responsibility for it.

Your debut film won the 2001 Grand Jury Prize at the Venice Film Festival. You are now working on a new film set in urban China. What do you think of the Chinese film industry?

I think it's even worse than the writing industry because the cost is higher - you need to pour in a lot of money and it involves a lot of people working for it, whereas writing is just one person's business.

You said you first took up writing to discover what you really wanted to do. Have you found your goal?

I haven't really found it yet. A lot of people devote their entire life to one thing: their career, such as writing or directing. I think there are always things that are more important than a career in life. I think the overall mission and task that I have is to live an honest and truthful life.