Rake-thin, his shins shiny with scars, 10-year-old Hei-hai is one of those characters who is hard to forget. He's the central figure in Mo Yan's Radish but doesn't say a word throughout: his silence makes his presence all the more powerful.

The novella was first published in Chinese in 1985, but it's only now - 30 years on - that it is available in English. Translated by Howard Goldblatt, it has been published as a Penguin Special and at fewer than 90 pages it is a fast, powerful read.

The story is set in collectivist-era China in the late 1950s. The leader of a rural work team recruits young Hei-hai to help build a floodgate even though he's too young and too weak for such hard labour. The boy doesn't have shoes or a shirt on his back and his baggy shorts are stained with grass and dried blood. His limbs are covered in scars and his ribs are clearly visible. The team leader even remarks to Hei-hai that "a fart would knock you off your feet".

These are the hard days of the Maoist revolution and despite his obvious vulnerability Hei-hai is put to work crushing stones. On the first day of work he smashes his thumb with the hammer. Juzi, a kind young woman with a round face, washes his thumb and wraps it in her handkerchief. But Hei-hai undoes the makeshift bandage and rubs dirt in the wound. He seems as immune to kindness as he is to danger.

His personal story is equally bleak. His father is missing and his stepmother is a drunk who beats him. No wonder he prefers to sleep under a bridge on a rough mattress of straw. After the hammer incident he's put to work pumping the bellows for the blacksmith's fire. The job is no less dangerous and he is soon covered in black soot and burns his arm on a red-hot chisel.

As Hei-hai lurches from one near fatal disaster to the next, sexual tension is building around him. Juzi begins a relationship with a good-looking mason, but he's not the only one attracted to her. The young, one-eyed blacksmith also has his eye on her and as the floodgate project drags on, one monotonous day's work after another, the sexual tension mounts. Hei-hai might not say a word, but he's well aware of what's going on around him.

When the blacksmith sees the mason touch Juzi's breast he gets excited - "Flames flew up into this throat and burst from his nose and mouth. It felt to him as if he were crouching on a taut spring, that if he let go he would shoot into the air to crash against the floodgate's steel and concrete surface".

That tension will eventually erupt in violence.

Goldblatt's translation does justice to Mo's rich prose. The characters are well fleshed out, but the finest descriptions are reserved for the world outside the intense confines of the work unit.

When the blacksmith sends Hei-hai out to steal radishes from a neighbouring farm we see the lush landscape. Nature is described in powerful detail and then thrown up against the harshness of life on a commune.

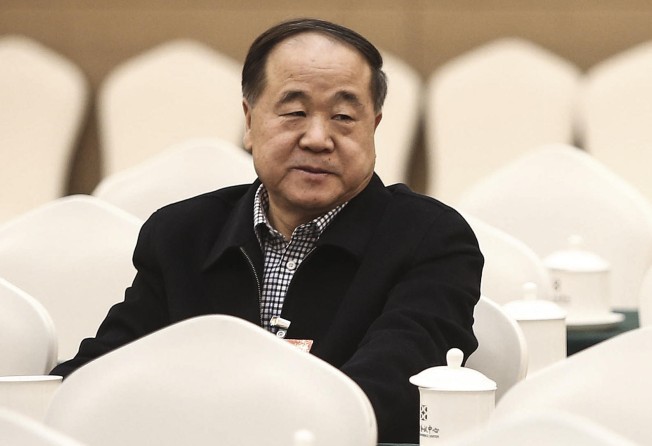

Unable to sleep, Hei-hai walks along the riverbank and "watches the sun cleave the mist like a knife through bean curd. Across the river, the ducks cast superior looks his way." In 2012, Mo won the Nobel Prize for Literature. If he hadn't, this 30-year-old story might never have been translated into English.

Now that non-Chinese readers can enjoy it, it serves as an affirmation that Mo's perceptive and carefully crafted prose makes him worthy of the prestigious award. When he picked up the award in Stockholm critics complained he was writing within the system, but Radish makes clear he's on the side of the common people.

Radish by Mo Yan (Penguin Special)